The small Texas town where I live, Marfa, is the home base of one of the largest U.S. Border Patrol sectors, covering 165,000 square miles and encompassing 25 percent of the U.S.-Mexico border. From my house, I can hear the Border Patrol headquarters' intercom, alerting agents to calls on line two or line three; their green and white patrol cars are everywhere, around town and throughout far west Texas. It's a daily reminder that we are living on the edge of a line in the desert, a line that Homeland Security is vigilant about protecting -- keeping certain people in and certain people out. A line that migrants will spend thousands of dollars, countless days and untold psychological turmoil trying to cross in an attempt to make it into America.

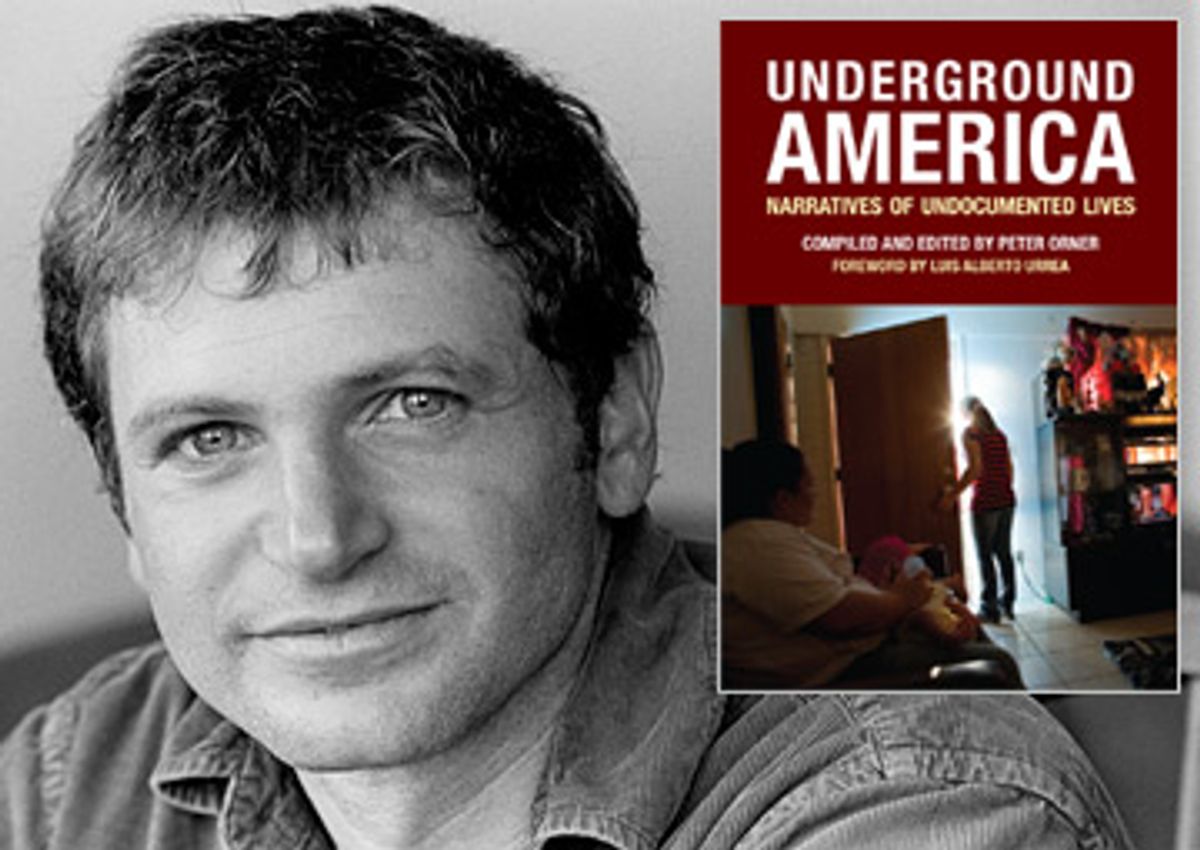

So it's fitting that writer Peter Orner was recently working in Marfa as a writer-in-residence for the Lannan Foundation, a literature and arts foundation in Santa Fe, N.M., that offers a residency program here. While Orner is a celebrated novelist and short-story writer -- his novel "The Second Coming of Mavala Shikongo" was a 2006 Salon Book Award winner -- his new book, "Underground America: Narratives of Undocumented Lives," marks his departure from fiction. ("Underground America" is the third of the McSweeney's Publishing "Voice of Witness" books, a series dedicated to documenting social injustice through oral history.) Through 24 narratives, Orner, who edited the book and led a 22-person interviewing team, gives voice to a small handful of the millions who've illegally crossed into this country.

We hear about these migrants on the news: We watch pundits discussing immigration, we see videos of walls on the Mexican border, we know that they are here. But what do we know of their daily lives: Why they came to the United States? What they left behind in their home countries? In "Underground America," Orner and his co-interviewers attempt to answer those questions. The stories are heartbreaking and human. "My only crime was working hard," says "Diana," a 44-year-old Peruvian migrant working in post-Katrina New Orleans. Eventually caught by immigration officials who refused her access to a lawyer, she was detained in a prison, wearing shackles and chains, and allowed to shower only once a week. After struggling in poverty in Guatemala, 28-year-old "El Curita" came to the U.S. dreaming of a better life; he worked as a housepainter for an American woman who used his lack of legal papers to force him into domestic slavery.

Rather than discuss "Underground America" over coffee, Orner and I crossed the border into Mexico, an hour away, for lunch. In Presidio, Texas, we drove over the trickling Rio Grande -- where five miles of the border wall will soon appear on either side of the crossing -- to Ojinaga, Mexico. After a lunch of chicken fajitas, we drove back across the border. On the American side, we silently perched on a concrete bench while border officials searched my car. It was a strangely intimate moment to share with someone I hardly knew.

In the introduction to "Underground America," you write that there are 15 million undocumented migrants in the U.S. That's an incredibly large group.

Congress estimates that there are between 12 and 15 million undocumented immigrants in the U.S., but the truth is that it's at least 20 million, we think. Every city, every little town in Iowa, all the meatpacking in this country, all the fruit picking -- it's all undocumented people.

So many of these stories are unbelievably nightmarish -- slave labor, sexual assault, riding in the back of a packed truck without bathroom access for days. Did everyone you interview have these kinds of experiences?

No. But everyone had some connection to the nightmare. To give you an example, one story that didn't make the book, that of a woman from the Hudson Valley in New York -- while we were interviewing her, she got a phone call. Her nephew had tried to cross over in the desert and was missing for five days. No one knew what happened to him. He was scheduled to arrive in Tucson or wherever at a certain date, and then he didn't show up. So you've got a missing nephew who may be dead in the desert, and you're on the phone in Hudson, N.Y.

So the issues are out there for most people in this situation. You're hard-pressed to find people who treat you wonderfully. There's this misnomer that they're here to steal our jobs and take our money. But the fact of the matter is, I didn't personally find any success stories.

Was it hard for your subjects to open up? You change their names, but there are a lot of details.

Right. The hardest thing, initially, was to gain people's trust. "Liso," the South African woman [who came to the U.S. on a missionary visa and mistakenly trusted the sponsors who promised to extend her status but instead let it lapse and forced her into domestic slavery] -- three of us interviewed her as a group. When we knocked on the door, she asked us 10 times if we were from Homeland Security. She asked in the middle of the interview, because she thought, Why are you asking all of these questions if you're not part of the government? She didn't trust us. Now she does. We went out, we had a meal, we spent a lot of time with her, and she started to trust us more. But there wasn't a reason to trust us at first.

The people we finally chose for the book were people who were very invested in having their story told publicly. They wanted to be heard in some way. And it should go without saying that we didn't pay anyone; it was all volunteer. In some cases, people did not want to talk. But I found, especially when there was an egregious human rights issue involved, people really did want to get that out, because they had no other way to tell that story.

They're frustrated by the injustice that they've already suffered. Like with "Olga" -- her daughter, who is also undocumented, is detained and is dying of AIDS. She has been chained to a bed, and the prison isn't giving her medicine. If you're "Olga," of course you want people to know that this is happening.

And these are people who live in the U.S., so they're accustomed to a society that has a relatively robust freedom of speech. So it's almost like, as I say in the book, what's more American than speaking? Ultimately, I think that's how they felt.

And even though undocumented people do have rights here, they feel like they can't get help. The women in the book who are sexually assaulted -- that's still against the law, whether they're legal citizens or not.

Absolutely. But what happens when they ask you about your status? This is a real issue. I mention this in the book -- when Mitt Romney, in the debate [against Rudy Giuliani], was scandalized that New York allows you to report a crime without saying your immigration status -- I've never been more angry at the television in my life. Because these are the very people that we're talking about in the book. In a lot of cases they're too afraid to report crime, but some people want to take even that right away.

Were you surprised at the number of stories involving slave labor?

Totally. But at a certain point, I stopped being really surprised because of the nature of where these people stand. They're vulnerable. You have, in many cases, a desperate population. They've got to feed their families. They need this job.

When I edited this book, I kept thinking, What would I do in this situation? I wouldn't do things a whole lot differently than most of the narrators in the book. Maybe I wouldn't have come in the first place. But I think in most cases, I probably would have. They're not here, in most cases, for the wrong reasons.

And they're very honest about why they came -- how they grew up hearing that the U.S. is welcoming, with good doctors, jobs, education for their kids. They have no idea it will be as hard as it is to survive here. And as you say, there's no such thing as economic asylum in the U.S. You can't just enter the country because your home country is impoverished. So what should they have done instead?

There is an asylum system that allows you to come in if you're being persecuted. A lot of people in our book were, in fact, being persecuted. A lot of the people in our book could have made decent asylum cases, but there are no guarantees. And when you're an asylum case, you're not allowed to work. So it's understood that you work illegally if you're here waiting for your asylum process. So how do you support your family if you are trying to do this?

What I found is that when someone did try to do things by legal means, like "Roberto," who'd been here 30 years, so he was in a special category of undocumented person -- he was allowed to apply to get a green card, and it turned out that since his wife had entered later, and there'd been some mix-up with her dates, they deported her and their kids. And this is a guy who'd been trying to do it the right way. So I think it's very difficult to do it the right away. People say, Oh, wait in line. But when you're poor and you're trying to make your life better -- I wouldn't go so far as to say people were starving, so it wasn't a completely desperate act. It was a choice. And that to me makes them more human. It's a human choice that people made, and as people they're more complicated than desperate masses streaming across the border. But there's a certain level of desperation, no question.

You told me earlier that you didn't want these stories to be "lessons."

Who wants to read a didactic book? I wanted these people to be rounded human beings and not victims. That's not who they are. They're complicated. They've made certain choices that have made their lives difficult, and our job was to look and see what the consequences of those decisions are. And some of them are not their responsibility, but some of them are. It's a vulnerable population, but they're not 100 percent victims at the hands of our society. It's more complicated than that. It's a relationship that's navigated by them and by us, to sometimes very bad and violent effect.

But children didn't choose it, and they're in a different situation, like "Estrella" [a 17-year-old high school student who has lived in the U.S. since she was 6 weeks old], who came over on her mother's back. All of her sisters are American, but Estrella is the one in her family who is most interested in education and getting a good job.

What do you think is the public's biggest misconception about undocumented workers? Is it more nuanced than the complaint about taking U.S. jobs and using U.S. services?

That's part of it. Also, a lot of the people in our book are quite conservative, politically and otherwise. They're more religious in most cases, very respectful of the law.

There is a baseline issue: They're in this country illegally. But even in that sense, there are differences. There's "Estrella" versus "Farid," who came here as a wealthy businessman and overstayed his visa. To us, they're undocumented. The government may have different categories, and may not lump them [together] in the same way, but the fact is that they're working and living here without papers.

But the misnomer is that they're criminals -- not just that they're sponging off of us. I think there's a perception that there's a great deal of crime coming out of these communities. That's preposterous, and only anecdotally can I say that.

Right, it's like, how much time do you have to commit crime when you're working 15 hours a day?

And the fact is, if you do commit a crime, you're exposing yourself. So they lie low. But like any population that lies low, they're easy to beat up on. And that's why we're in the situation we're in. They're vulnerable, and that's why people go after them. They're trying to feed their families, get their kids in school. They're like any immigrant population. They're trying to have the next generation move forward.

One of the interesting aspects of the histories is the number of professional people -- people like "Elizabeth" [a Bolivian English teacher who came to the U.S. searching for treatment for her gravely ill daughter], who aren't impoverished but come over for other reasons, like medical care.

Yes, and we assume that none of these people are college educated, that they're just peasants. "Dixie" was a school administrator, and she ended up working at Wendy's and McDonald's.

They're thrust into these situations and they have to survive. Dixie is not a tough lady. She didn't want to work at Wendy's. She wore high heels to that job. I think she'd say, No, I just needed to survive.

Did your feelings change about the project the longer you worked with these narratives?

To be trusted with people's stories -- I felt very responsible for them. We did the best we could to protect their identity, but they were taking a risk in talking to us.

I came into it not knowing as much as I know now about the issue, but I also think this is an emergency. I didn't know that then. My small hope is that this book contributes to understanding the complexities of these people's personal lives and understanding that they're in crisis. And that something needs to be done to protect people -- to protect kids and others from being harmed.

Do you think an administration change could help that?

Hillary Clinton wasn't good on this issue. Barack Obama has been awfully quiet about it. I think his heart's in the right place, but I think the pressures of anybody is his position are very grave. And I also think that this is not a population that you need to worry too much about if you're a politician. You just don't. So I'm cautiously optimistic.

Shares