Sherwood Anderson, your time has come. Again.

Last month, Philip Roth's novella, "Indignation," created a WASP bastion named Winesburg College in your honor. This month, you're a flesh-and-blood fictional character. In the opening pages of "The Wettest County in the World," you've come to southwestern Virginia to revive a flagging career. Old protégés like Hemingway and Faulkner have turned on you; your dreams of starting a "rustic literary salon" have come to naught; the two local newspapers you're editing have sucked away your life force; and you live in the shadow of a "nameless terror … some great thing, swaying, descending."

The only thing to do is to find a new story, and here it comes. A sensational murder trial featuring the notorious Bondurant brothers, Virginia moonshiners who've spent the waning years of the Depression battling law enforcement. Begin with Jack, the youngest brother, barely a man, his feet permanently scorched by lightning, his soul averse to "bloody work." Like any young man, he's "convinced that his fortunes would be different from the fortunes of those who struggled around him," and he's waiting for the big score that will let him blow town once and for all.

Continue with the oldest Bondurant: Howard, a massively built war veteran who can't drink away his pain fast enough. ("How much liquor is there in this county? In this world?" his wife asks. "Might try to find out," Howard says.) And finish up with middle brother Forrest, who meets "the grinding labor of adulthood and death" with "narrowed eyes, knotted fists, and silence." On Forrest's neck: a ragged white scar, a testament to the night he walked 12 miles in the snow with a slit throat, a feat that has made him a dark local legend.

The Bondurant boys have carved out a healthy little slice of Franklin County's moonshine market, which has not escaped the law's notice. The local sheriff and D.A. offer to ensure safe passage of the brothers' product if the Bondurants fork over $20 a month in protection money, plus $30 a load. Just enough to eliminate whatever profit margin moonshining provides. Forrest flatly refuses. "We control the fear," he snarls. And Jack, dazzled by his brother's omnipotence, thinks: "Nothing can kill us."

But a lot of people will certainly try. "The Wettest County" features (in no particular order) knifings, shootings, beatings, rapes and, in Anderson's helpful précis, "cars full of liquor blasting through the town square every night with women at the wheel, men getting castrated and their testicles delivered to them in the hospital, and nobody seems to care or say anything about it."

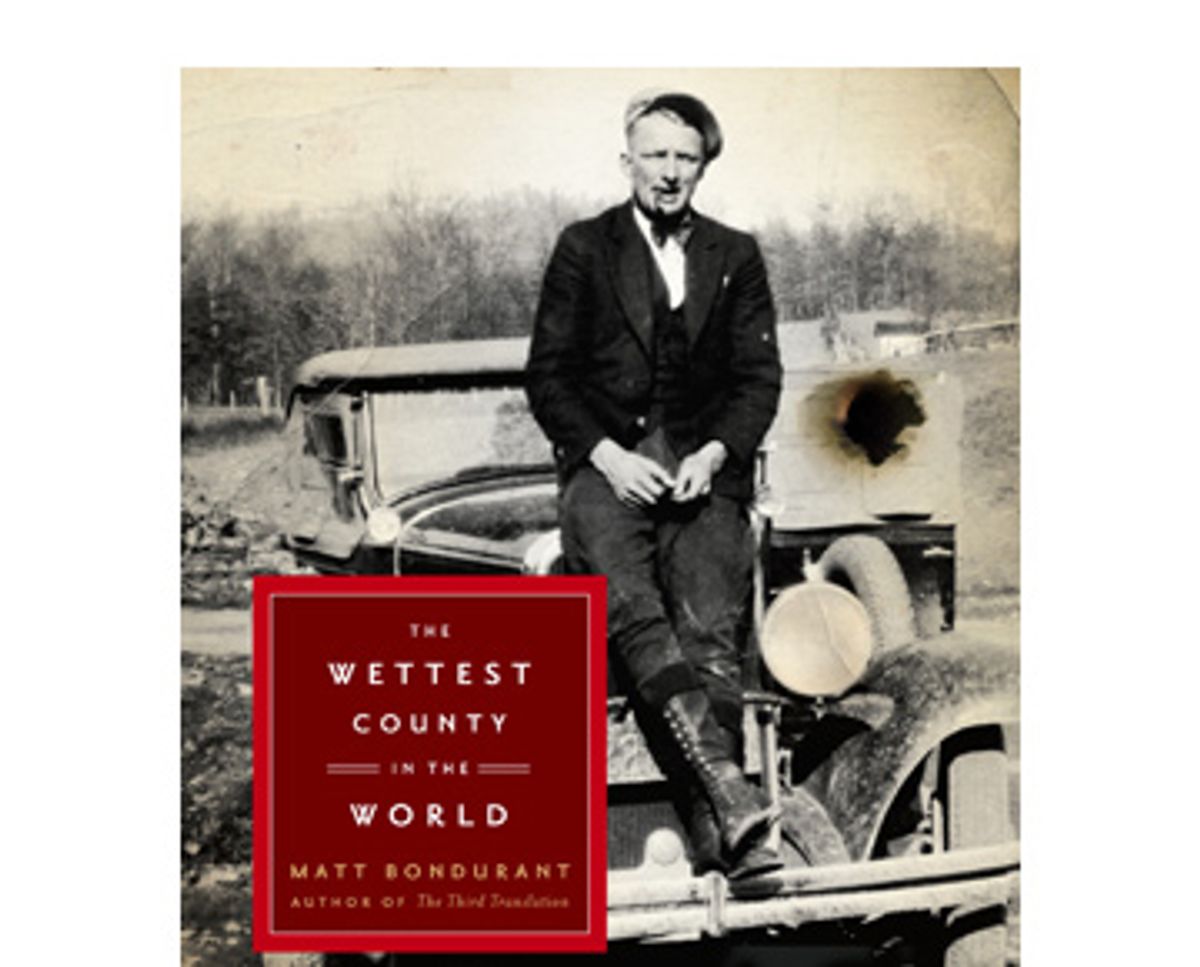

Actually, somebody cares very deeply: the author, Matt Bondurant, who happens to be the real-life grandson of one of those bootlegging brothers. That biographical frisson wouldn't matter so much if Bondurant didn't give the impression of having walked and talked with these people all his life. He's smelled the clover and the corn whiskey. He knows that a young man, trying to impress a young woman, will prop his feet on the running board of his brand-new Dodge Sport Coupe and flick away his cigarillo. He's really seen these hardscrabble folks -- and not just in a Dorothea Lange photograph -- their slumped shoulders and sun-scarred necks, the "old men clustered in general stores, on the front porches of the filling stations, the haggard old crabs at the quilting bee, the thin spittle of bitterness bubbling on their lips, their razor eyes, the angry shaking of their bobbing skulls."

Judged simply by its story arc, "The Wettest County" could be an expanded-cable updating of "The Untouchables," but Bondurant's bootleggers are eminently touchable and, even in their worst moments, touching. This is a lyrical and riveting book about "the dreams of wadded sums of cash, of heavy lumps of change in your pocket, the small stacks that speak of little dreams." It's a book that hurts like life.

Shares