Rick Steves has ruined Europe, I tell you. You can't stay in any of the great boutique hotels in Paris, London or Rome anymore because they are booked by Americans who have studied Steves' guidebooks like Sanskrit scholars. Nor can you find solitude in cafes in pastoral Austria or Switzerland because they are peopled with Steves' tours.

Author Timothy Egan told a funny story in the New York Times last year about having lunch in Vernazza, in the Italian Cinque Terre, "watching waves of people pour into the tiny village to look for their serendipitous Stevesian encounter while clutching his guidebook. A sudden outburst came from my 7-year-old son: 'Rick Steves has got to be stopped!'"

Steves laughed out loud when he read that line, he told me. But see, that's the problem. He's so good-natured and devoted in his PBS travel specials to showing places that Fodor's would never send tourists to in their floral shirts that he's created a monstrous new travel industry. He's the apotheosis of the anti-Carnival Cruise crowd.

Oh, well, what are you going to do? I've used his books in Europe myself. But there's an activist side to Steves that many of his fans may not be aware of. Behind his abnormal geniality thrums a daring political agenda. Not a didactic one, mind you, but a Rick Steves one.

In short, Steves wants Americans to get over themselves. He wants us to please shed our geographic ego. "Everybody should travel before they vote," he has written. We should be represented by politicians who want America to act as a good global neighbor.

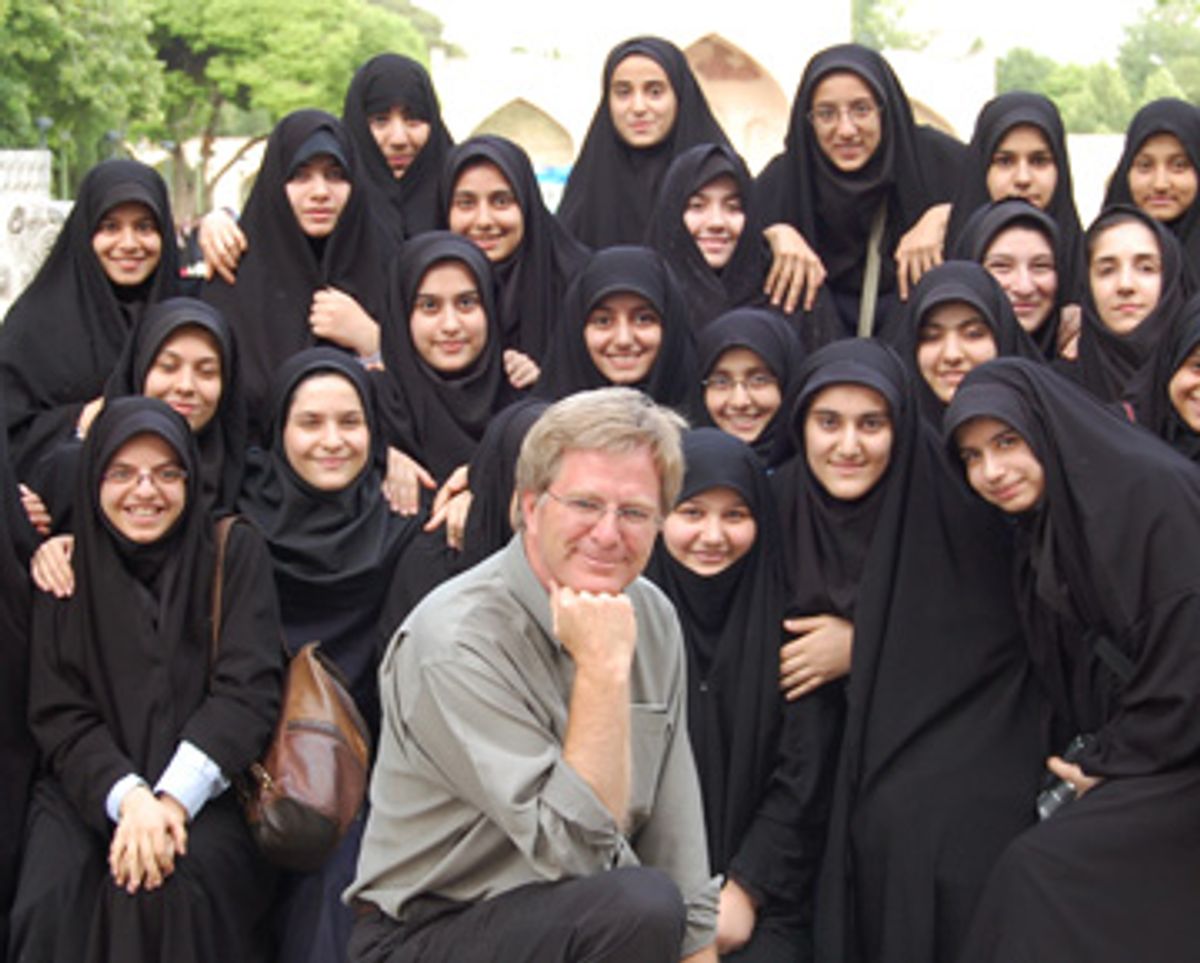

Steves' agenda is epitomized in his recent TV special on Iran. At the request of a friend in the United Nations to help "build understanding between Iran and the U.S.," Steves has produced a loving portrait of the demonized country. Characteristic Steves-on-the-street interviews open closed minds to the sophistication of Iranian citizens and their lack of antipathy toward Americans. In one scene, a man in a car pokes his head out the window and says to Steves, "Your heart is very kind." Steves is incredibly proud of his Iran film and is offering the DVD for $5 to any community group that wants to discuss it.

I recently caught up with Steves while he was killing time in the Tulsa, Okla., airport, where he had just given a talk about Iran, and was heading home to Washington state. In conversation, he was as ebullient as ever, fearlessly spelling out his views on globalization and terrorism, the scourges of tourism and the importance of decriminalizing marijuana.

Conservatives continue to harp that the U.S. shouldn't negotiate with Iran, and call Obama weak for even appearing agreeable toward the country. What can your Iran show say to American hard-liners?

When I made the show, I was not interested in endorsing or challenging the complaints we have about Iran's government. Maybe they do fund terrorism, maybe they do want to destroy Israel, maybe they do stone adulterers. I don't know. I just wanted to humanize the country and understand what makes its people tick.

When I came home after the most learning 12 days of travel I've ever had in my life, I realized this is a proud nation of 70 million people. They are loving parents, motivated by fear for their kids' future and the culture they want to raise their kids in. I had people walk across the street to tell me they don't want their kids to be raised like Britney Spears. They are afraid Western culture will take over their society and their kids will be sex toys, drug addicts and crass materialists. That scares the heck out of less educated, fundamentalist, small-town Iranians, which is the political core of the Islamic Revolution and guys like Ahmadinejad.

After all, this is a country that lost a quarter of a million people fighting Saddam Hussein, when Iraq, funded by the United States, invaded Iran. And they remember the invasion like it was yesterday to them. It's amazing: They have a quarter of our population and they lost a quarter of a million people, fighting Hussein. That's a huge scar in their society.

I just feel we underestimate the spine of these people. They will fight and die to defend their values. And their values are not to destroy America and Israel. Their values are to defend their way of life against Western encroachment. Because of recent history, they have grounds to think America threatens them. So it would be dangerously naive to think we could shock and awe them into any kind of submission.

Do you want your film to have a political impact in the U.S.?

Well, yes. I talked to 2,000 people in Tulsa today. After I explained this to them, I am convinced they now have a little less self-assuredness in thinking that Iran is the evil our government wants us to think it is. I was actually scared to go to Iran. We almost left our big camera in Athens and took our little sneak camera instead. I thought people would be throwing stones at us in the streets. And when I got there, I have never felt a more friendly welcome because I was an American. It was just incredible. I was in a traffic jam in Tehran, a city of 10 million people, and a guy in the next car saw me in the back seat and had my driver roll the window. He then handed over a bouquet of flowers and said, "Give this bouquet to the foreigner in your back seat and apologize for our traffic."

Did you edit out any scenes that might have portrayed Iranians in a negative light?

No. I was very upfront in the show that I wasn't there to do things like visit nuclear plants. Some people say, "You're just being duped, you got a minder, he's only going to show you the good parts of the country." But we went through streets with angry anti-American posters. We showed that. You see the "Death to America" thing.

I do want to make clear that Iran is not a free society. They traded away their freedom for a theocracy, out of fear. It's just like Americans. We don't want to torture people, we want to have civil liberties, we don't want our government reading our mail. But when we have fear, we let fear trump our commitment to our civil liberties and decency. We allow torture, we allow the government to read our mail. It's not because we're bad, it's because sometimes fear is more important than our core values. And Iran is afraid. They've given up democracy because they know a theocracy will stand strong against encroaching Western values.

In your 2004 essay "Innocents Abroad," you wrote: "To even consider the terrorists' concerns (U.S. military out of Islam, Arab control of oil, security for Palestine) is out of the question in today's America. But the passions are strong enough and technologies of mass horror are accessible enough that radicals/heroes/terrorists/martyrs from angry lands … will certainly strike again if no one listens to their concerns."

Oh, yeah. I just feel more strongly about that than ever.

That sounds like you were being sympathetic to terrorists. Were you?

No. I'm trying to be empathetic to what motivates them. We think they're terrorists, but we have to remember that 96 percent of the planet is not American. And most of them look at us like an empire. When I write about us being an empire, it touches a nerve more than almost anything else I write. I get so much angry feedback.

But I don't say we're an empire. I say the world sees us as one. I say there's never been an empire that didn't have disgruntled people on its fringes looking for reasons to fight. We think, "Don't they have any decency? Why don't they just line up in formation so we can carpet bomb them?" But they're smart enough to know that's a quick prescription to being silenced in a hurry.

We shot from the bushes at the redcoats when we were fighting our war against an empire. Now they shoot from the bushes at us. It shouldn't surprise us. I'm not saying it's nice. But I try to remind Americans that Nathan Hales and Patrick Henrys and Ethan Allens are a dime a dozen on this planet. Ours were great. But there's lots of people who wish they had more than one life to give for their country. We diminish them by saying, "Oh, they're terrorists and life is cheap for them." They're passionate for their way of life. And they will give their life for what is important to their families.

As a travel writer, I get to be the provocateur, the medieval jester. I go out there and learn what it's like and come home and tell people truth to their face. Sometimes they don't like it. But it's healthy and good for our country to have a better appreciation of what motivates other people. The flip side of fear is understanding. And you gain that through travel.

But even saying you're trying to understand terrorists' motives still grates. Don't you think?

Yeah, people don't like to hear that. They think it's showing weakness to the terrorists. But we have to think more carefully about why we are angering so much of the world. I'm just trying to say, Hey, look, we're 4 percent of this planet, we've spent as much as everybody else together on the military, and we've got military bases in 130 countries. Yet only we can declare somebody else's natural resources on the other side of the planet are vital to our national security. Only we can be pissed off if they elect a government that nationalizes their own natural resources.

We wonder why didn't God give us those resources. I don't know what motivates us to think we've got rights to their natural resources. This is poignant stuff, and a lot of Americans don't want to hear it. But I just want to come home and remind my neighbors that we've got to work with this world. Our military and economy is not strong enough to have a unilateral foreign policy. We're not strong enough to go it alone.

You've lamented that 80 percent of Americans don't have passports. And yet we almost had a vice president who didn't have one until 2006, and in fact criticized passports as a sign of elitism.

I remember that. She put travelers down as a latte-sipping crowd.

What would it have done to America's reputation abroad if John McCain and Sarah Palin had won the election?

People cut us some slack for electing Bush the first time. He was an unknown quantity. But the second time we elected him, people just shook their heads and said, "There is no excuse for this." They knew he was a unilateralist -- our way or the highway. And so what if we're outvoted in the United Nations 140 to 4? Don't you know that's because the four nations -- the United States, Israel, Marshall Islands and Micronesia -- are the compassionate, enlightened coalition, and everybody else is clueless? That kind of thinking astounds our friends abroad.

If we had a terrorist event six months ago, we would have McCain for president today. Because fear would have driven us to the hard-liner on the right. And thank goodness we didn't have fear raging in our society during the election, so we could elect somebody who wants to talk with the rest of the world. The irony is we make the future more dangerous by not talking to the rest of the world. We can be a part of the family of nations. We don't need to be a pushover. We can promote our values in a respectful, civilized way. That's just more pragmatic and more productive.

So if McCain and Palin had won, what would we have seen abroad?

More and more Americans wearing Canadian flags.

What are the international consequences of Obama's victory?

We're part of the family of nations again. If you go to Europe wearing an Obama T-shirt this summer, you're going to get free drinks all around. I'm just so excited that America can provide leadership again. When we opt out of these things, we're not providing leadership. We think we can coerce people into going along with us, but all we do is isolate ourselves. And the world moves on without us. If the world moves on without us, one day we'll wake and we'll find we're rich only in weaponry, and everybody else is rich in other ways. Then our little house of military cards will collapse on itself, and we'll be a second-rate nation.

What's the most important thing people can learn from traveling?

A broader perspective. They can see themselves as part of a family of humankind. It's just quite an adjustment to find out that the people who sit on toilets on this planet are the odd ones. Most people squat. You're raised thinking this is the civilized way to go to the bathroom. But it's not. It's the Western way to go to the bathroom. But it's not more civilized than somebody who squats. A man in Afghanistan once told me that a third of this planet eats with spoons and forks, and a third of the planet eats with chopsticks, and a third eats with their fingers. And they're all just as civilized as one another.

Do you think Americans are more provincial or racist than people in other countries?

The "ugly American" thing is associated with how big your country is. There are not just ugly Americans, there are ugly Germans, ugly Japanese, ugly Russians. Big countries tend to be ethnocentric. Americans say the British drive on the "wrong" side of the road. No, they just drive on the other side of the road. That's indicative of somebody who's ethnocentric. But it doesn't stop with Americans. Certain people, if they don't have the opportunity to travel, always think they're the norm. I mean, you can't be Bulgarian and think you're the norm.

It's interesting: A lot of Americans comfort themselves thinking, "Well, everybody wants to be in America because we're the best." But you find that's not true in countries like Norway, Belgium or Bulgaria. I remember a long time ago, I was impressed that my friends in Bulgaria, who lived a bleak existence, wanted to stay there. They wanted their life to be better but they didn't want to abandon their country. That's a very powerful Eureka! moment when you're traveling: to realize that people don't have the American dream. They've got their own dream. And that's not a bad thing. That's a good thing.

Echoing Paul Bowles' famous line, what's the difference between a tourist and a traveler?

I'll give you an example. A few years ago, my family was excited to go to Mazatlán. You get a little strap around your wrist and can have as many margaritas as you want. They only let you see good-looking local people, who give you a massage. There's nothing wrong with that. But I don't consider it travel. I consider it hedonism. And I have no problem with hedonism. But don't call it travel. Travel should bring us together.

That same week, I was invited to go to El Salvador and remember the 25th anniversary of the assassination of Archbishop Oscar Romero. I thought, "I'm not going to be any fun on the beach in Mazatlán, I have to go to San Salvador." So I went down there and I had a miserable, sweaty dorm bed, covered with bug bites. We ate rice and beans one day, and beans and rice the next day. But it was the richest educational experience. It just carbonated my understanding of globalization and the developing world, and Latin America. I was in hog heaven. And I've been enjoying souvenirs from that ever since. Whereas my wife just gained a few pounds on the beach in Mazatlán.

Do you think tourism gets in the way of experiencing a foreign place?

Oh, yeah. But if you're savvy, you understand the tourism industry just wants to dumb you down and go shopping. So you have to be smart. I was just in Tangiers, which is where all the people go from Spain's Costa del Sol resorts for their one day in Africa. It's a carefully staged series of Kodak moments. They have a lunch. They see a belly dancer. They see the snake charmers. They buy their carpet. And they hop back on the boat to Spain. When I see them, I can't help but think of a self-imposed hostage crisis. They put themselves in the control of their guide and never meet anybody except those who want to make money off of them. It's a pathetic day in Africa.

Did you ever read the Don DeLillo novel "The Names," which takes place in Greece?

No.

I always remember this line from it: "Tourism is the march of stupidity."

That's a great line. And that's my challenge. I write somewhere in one of my books that my kind of travel fits the industry like a snowshoe in Mazatlán. That's our challenge: to offer Americans, who are thoughtful and curious, a way to be thoughtful in their travels.

Of course, that's also your own consumer brand.

Yes, it's been quite a publicity stunt! If all I was doing was selling timeshares in Mazatlán, I would not be getting anywhere near the exposure, generating the business I'm doing. And, on the serious side, getting Americans to think about Iran or drug policy.

How did the decriminalization of marijuana become such a passion of yours?

We're blowing $10 billion a year criminalizing a drug that's no more dangerous than alcohol or tobacco. Nobody is saying drugs are good. People are just saying it's smarter to treat drug abuse as a health problem instead of a criminal problem. Some societies measure the effect of their drug policy in incarceration; others measure it in harm reduction. America's into incarceration, Europe's into harm reduction. I just bring the European sensitivity home to America.

Was there one experience that opened your eyes to the issue?

A lot of my outlook and writing have been sharpened by enjoying a little recreational marijuana. If you arrested everybody who smoked marijuana in the United States tomorrow, this country would be a much less interesting place to call home.

The fact is, the marijuana law in the U.S. is a big lie. It's racist and classist. White rich people can smoke marijuana with impunity and poor black people get a record, can't get education, can't get a loan, and all of sudden go into a life of desperation and become hardened criminals. Why? Because we've got a racist law based on lies about marijuana.

There's 80,000 people in jail today for marijuana. We arrested 800,000 people in the last 12 months on marijuana. Even in my rich little white suburban community of Edmonds, Wash., 25 percent of police action is marijuana-related. Everybody knows it's silly. I'm not saying I'm pro-drug. I'm just saying it's parallel to alcohol prohibition. When they rescinded the laws against alcohol, nobody said booze is good, they just said it was stupid to make it a crime, that you're creating organized crime and people are dying.

Where's the best place to smoke marijuana in Europe?

With good friends. I love the ambience in a little vegetarian restaurant in Copenhagen. Or coffee shops in small-town Holland. The big city coffee shops -- the menus look like a drug bust -- are full of people who are pierced and tattooed and dreadlocked. That's not my crowd. But go to a small-town coffee shop and you end up talking about philosophy and music with 50-something locals who just drop in to chat and relax. It's like a pub.

Given the lousy economy, can we still afford to travel?

These economic times are scary and who knows where we're heading. But it's dangerous to measure where we're at today by the unrealistic high a year ago, which was the result of years of goosing our economy to make us believe we're wealthier than we are. I could say our tours are down 30 percent. And they are. But that's not really true. Our tours are below the impossible height they reached last year. But they shouldn't have been that high anyway. We're taking 8,000 people instead of 12,000 people to Europe this year. And that's OK.

A headline today said, "Americans lose 18 percent of their wealth." Well, no, it wasn't real wealth, it was a bubble. You're down 18 percent? You're not. It shouldn't have been up there in the first place. So get over it. Shut up. Go to work, produce stuff that has value. I really think the days are gone, I hope, when people can rearrange the furniture and get rich on it. You got to produce something.

The interesting thing is we're all in it together. What I'm sad about is that when America catches a cold, the developing world catches pneumonia. And that's happened now. And a lot of Americans are feeling sorry for themselves because they can't have that fancy whatever-they were-going-to-get. But they have to remember that the gap between the haves and have-nots is even more pronounced and more desperate now. You're suddenly worried about how much is in your retirement account, but other people are worried about how much is on their dinner plate tonight. That's the reality.

So your advice is to keep travel in the budget?

I never met anybody who was a good traveler and invested time and money in a trip and regretted it. It's a great life experience. And if you can't afford it, I understand. But remember, life is short. The good old days are here now. If you spend your whole life thinking the good old days are ahead of you, you're going to wake up with regrets that life passed you by. Of course, I sell tours and guidebooks. So I need to talk it up!

Shares