"Star Trek" is a cultural comet. From its tiny, ancient core -- a mere 79 episodes, airing before we set foot on the moon -- a seemingly infinite tail has grown, its glow still bright after 43 years. The original series (featuring James T. Kirk, Mr. Spock and Dr. "Bones" McCoy) ran for just three seasons, from 1966 to 1968. All of the techno-bling we associate with the show -- communicators, transporters, warp drive, phasers and Tribbles -- was introduced during that first run. It’s staggering to reflect that the premier episode aired during NASA’s two-man Gemini program -- five years before the first pocket calculator.

On Friday, May 8, the newest offering in the "Star Trek" canon will open in theaters around the world. The film will give us the back story of the original series, and show how its three principals got themselves onto what might be (along with Noah’s Ark and the Titanic) the most famous vehicle in history: the starship Enterprise. Only one of the three main actors of that era will appear in J.J. Abrams' "Star Trek." It won’t be William Shatner (Kirk), or DeForest Kelley (McCoy), who died in 1999. Though Mr. Spock’s role as a half-human, half-Vulcan Starfleet cadet is played by Zachary Quinto, Leonard Nimoy makes a cameo appearance as the future Spock, coming to advise his younger avatar.

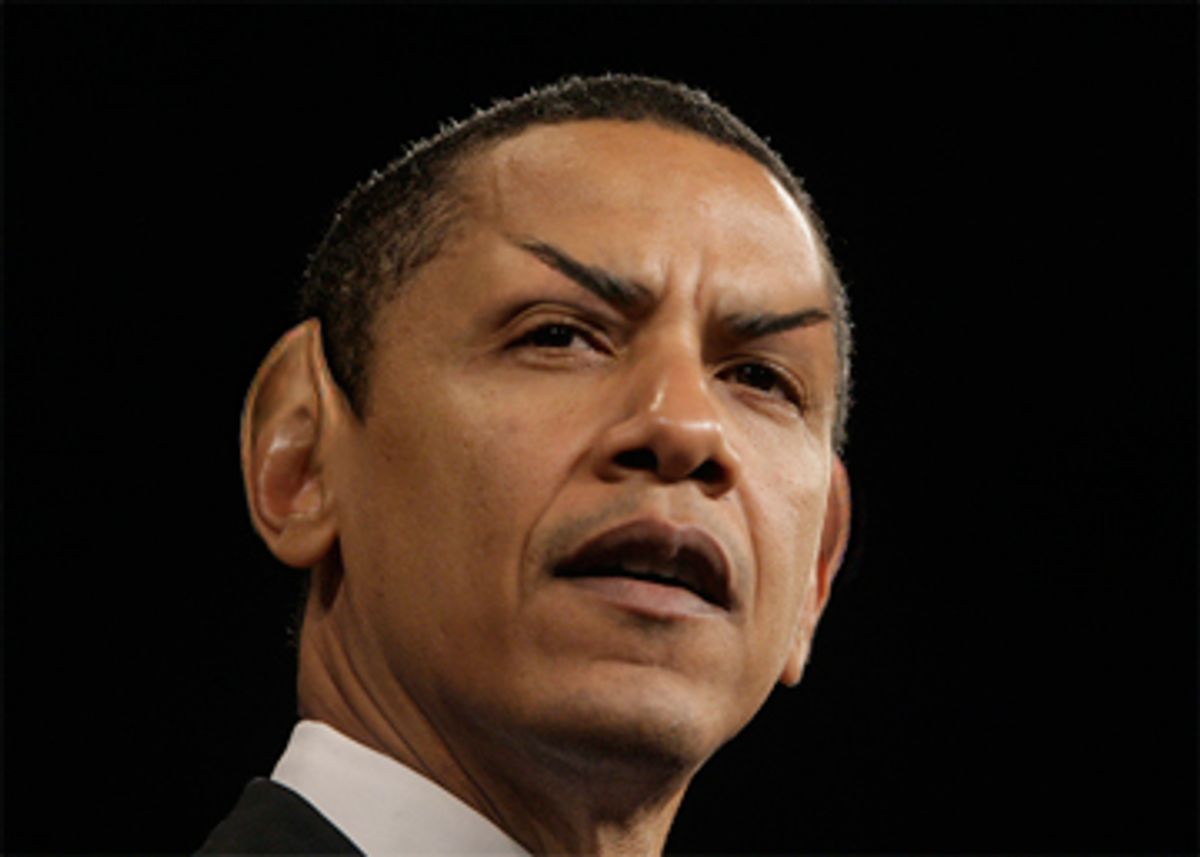

Spock has been on many minds lately, and not entirely because of the new film. Big thinkers in both print media and the blogosphere -- from New York Times columnist Maureen Dowd to MIT media moguls -- have referenced the Enterprise's science officer in recent months, drawing parallels between the dependably logical half-Vulcan and another mixed-race icon: Barack Obama.

They're not just talking about the ears. For those of us who watched the show in the 1960s (or during the countless reruns since), Nimoy's alter ego was the harbinger of a future in which logic would reign over emotion, and rational thought triumph over blind faith. He was a digital being in an analog world; the Pied Piper who led our generation into the Silicon Age.

Anyone who followed the early "Star Trek" with regularity knows how charismatic Spock was. If there were two characters I wanted to be as a young man, they were Spock -- and James Bond. Both displayed total self-confidence, and amazing problem-solving skills. Both traveled to exotic destinations, and were irresistible to women. And both shared a quality that my generation lacked completely: composure.

While Bond had his weaknesses (anything in a bikini), Spock was virtually unflappable. The most startling marvels in the cosmos were "fascinating." Disasters were "unfortunate," perhaps even "tragic." The raised eyebrow, the lifted chin, the vaguely sarcastic mien -- these were coins of the realm to my pubescent friends. How did we weather the terrors of grade school, and survive the irrational outbursts of parents and teachers? By invoking Spock. Who served as our logical, enlightened counterpoint to the madness of the late 1960s? Who else but Spock?

"I am a first-generation 'Star Trek' fan, and I've long argued that many of my deepest political convictions emerged from my experience of watching the program as a young man growing up in Atlanta during the civil rights era," declares Henry Jenkins, co-director of the MIT comparative media studies program and author of "Convergence Culture." "In many ways, my commitment to social justice was shaped in reality by Martin Luther King and in fantasy by 'Star Trek.'”

Obama, Jenkins points out, positioned himself in the primaries as a man "at home with both blacks and whites, someone whose mixed racial background has forced him to become a cultural translator." In this sense Obama even surpasses Spock, whose struggle to reconcile his half-human, half-Vulcan genes is a continual source of inner conflict. In one episode, the entire Enterprise crew (except for Kirk) is infected by alien spores that turn them into doe-eyed flower children. The "cure" is anger -- thus Kirk is forced to provoke his first officer to rage. He succeeds, spectacularly, by insulting Spock’s racial pedigree: "All right, you mutinous half-breed! You’re an overgrown jackrabbit! An elf, with a hyperactive thyroid! A simpering, devil-eared freak whose father was a computer and his mother an encyclopedia!"

Confronted with a similar insult, Barack Obama would probably just laugh. "The Vulcan side of Obama, the core of his character, hasn't changed [since the election]," Jenkins believes. "He's tough, he’s cool and he’s rational." His appeal stems from the self-aware integration of all aspects of his personality: black and white, wonk and poet, athlete and aesthete.

Like Spock, part of what makes Obama so appealing is the fact that although he’s an outsider -- "proudly alien," as Leonard Nimoy once put it -- he uses that distance to cultivate a sense of perspective. And while we're drawn to Spock's exotic traits -- the pointy ears, green blood and weird mating rituals -- we take comfort in his soothing baritone, prominent nose and ordinary teeth.

Spock's appeal, according to the actor who portrayed him, came from cultivating this dichotomy. In 1997, I interviewed Nimoy for my book "Future Perfect: How 'Star Trek' Conquered Planet Earth." "There is a sensitive side to Spock," Nimoy said, "to which a lot of people, male and female, responded. Also very important -- at least I thought it was, because it was what I was constantly playing -- is the yin/yang balance between our right and left brains. How do you get through life as a feeling person, without letting emotions rule you? How do you balance the intellectual and emotional sides of your being?"

The early Spock's only real vice was sardonic ire (often directed at McCoy). But this was also one of his most appealing qualities -- because Spock, as Jenkins gleefully asserts, is "someone who can bitch slap you with his brain." It’s an ability shared by Obama -- who, unlike Spock, doesn't employ that superpower recreationally. His brilliance isn't a defense (or defended by sarcasm). While Obama embodies Spock's passion for reason, he adds the element of warmth.

"Star Trek" fans who bonded with Spock already understood what those of us who followed Obama learned early on: that witnessing a powerful intellect can be deeply satisfying on an emotional level. We got a similar hit from Martin Luther King Jr. and the Kennedys, of course, and from Bill Clinton. But while Clinton's administration was smart, Obama's seems futuristic.

"Bill Clinton promised a Cabinet that looked like America," Henry Jenkins said in a recent conversation. "Obama gave us one that looks like the Enterprise crew. In a matter-of-fact way, he's embraced diversity at every level. No Klingons yet -- but the administration is new."

During the months that I researched "Future Perfect," people all over the world admitted a longing for the zeitgeist of "Star Trek." "The Enterprise crew was a professional team of people solving problems together," agreed Nimoy. "It was always a very humanistic show, one that celebrated the potential strengths of mankind, of our civilization, with great respect for all kinds of life, and a great hope that there be communication between civilizations and cultures."

Which is another reason why the sometimes audacious diplomacy of the Obama administration is innately appealing to those of us weaned on the credo of "exploring strange new worlds" and "seeking out new life and new civilizations." And what if the Earth itself was visited by aliens? If benevolent ETs were to land on the Mall tomorrow, most of humanity would be proud to have Barack Obama speak for us. If Bush were still president, we'd be looking at "Mars Attacks."

The problem with smart, thoughtful people is that you have to pay attention. Even with "Star Trek," some viewers complained that the stories were too complicated, requiring too much focus for the average TV viewer. Nimoy sympathized. "'Star Trek,'" he reflected, "was a language show. A lot of the ideas were expressed verbally. It has been said -- and I think it's true -- that if you didn't listen to 'Star Trek,' you couldn't follow the stories."

The same could be said of today's White House: It's a language show. "Issues are never simple," Obama has said. "Very rarely will you hear me simplify the issues." The stakes are high, the narrative is complex, and no one's talking down to us.

Obama, like Spock, rewards close listening. His cool logic is a real departure from what we've grown used to. Often presidential speechmaking is an emotive art, where oratory trumps reason. What was being said was often confused with how it was being said. We could watch Ronald Reagan with the sound off, and get a pretty good sense of how we were supposed to feel. Bill Clinton's richly accented arias lulled us, while reactions to the appearances of George W. Bush -- pro or con -- were driven less by analysis than by a limbic, visceral response.

Not that we don't have a visceral response to Obama. But it's a very different feeling, a pride of possession familiar to old-school "Trek" fans, whose millions of letters kept NBC from canceling the show in 1967. That victory -- one of the first cases of the mass media being influenced by overwhelming grass-roots support -- gave Trekkers the indelible sense that "Star Trek" was theirs. And while none of Obama's individual supporters can claim ownership of his presidency (any more than "Star Trek's" fans write the movies), they're well aware that it was similar grass-roots movements -- on the Internet, at thousands of small-scale fundraisers and on the streets of contested states like Ohio and Florida -- that sustained his phenomenon.

So we come, unavoidably, to the Big Question: What would Barack Obama himself say to this comparison? How might our president respond to the cartoons circulating on the Internet, showing him sporting Vulcan ears and a Starfleet tunic? In a September 2008 broadcast of the popular NPR show "Wait Wait … Don't Tell Me!" guest Leonard Nimoy recalled a recent encounter with a fan.

"About a year and a half ago, I was at a political event. One of our current campaigners for the office of president of the United States saw me -- and as he approached, he gave me the Vulcan hand signal." You can practically hear Nimoy's eyebrow raise. "It was not John McCain."

Shares