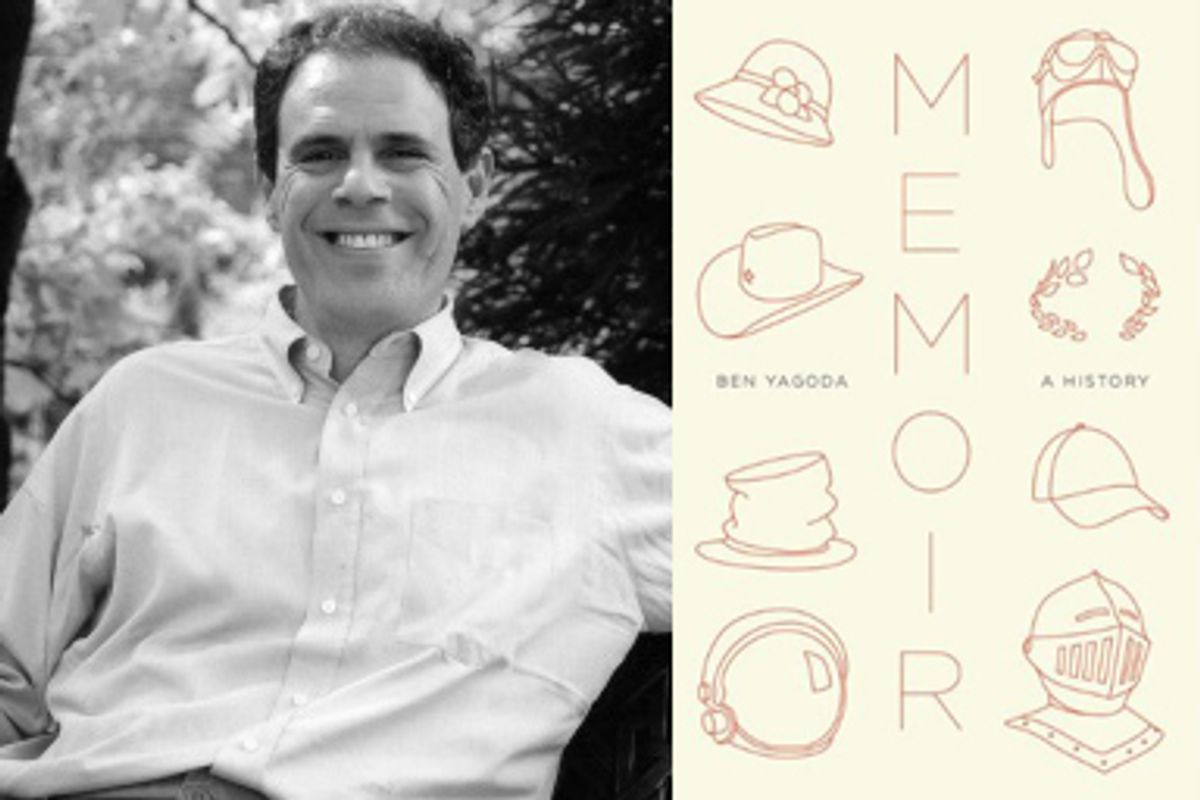

Has the memoir become the "central form" of our culture, as Ben Yagoda insists in his breezy new consideration of the form, "Memoir: A History"? Do I detect hackles rising from coast to coast at the mere suggestion? Today, autobiography is both very popular and widely reviled, for reasons that aren't always clear. People complain that the modern memoir is narcissistic, formulaic, pretentious and often falsified -- all true on occasion, though when pressed the accusers can usually list a few contemporary memoirs that they do admire. What is it about the memoir in its current form that makes it simultaneously so irresistible and so annoying?

As Yagoda entertainingly demonstrates, none of the criticisms and debates about today's memoirs are unprecedented. From the very beginning (if by the beginning you mean the "Confessions" of St. Augustine and "The Life of Benvenuto Cellini," written in the 5th and 16th centuries, respectively), autobiography has been subject to attacks on its appropriateness and veracity. There was no blogosphere to accuse Cellini of being way too self-absorbed, or to fact-check the full extent of St. Augustine's chastity, however, and by now their books are wrapped in the distinguished mantle of history. If you think that today's memoirs are the last word in TMI, then consider the case of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, perhaps the most influential autobiographer of all time, who treated his shocked 18th-century readers to descriptions of his masturbatory practices and professions of his desire to be sexually dominated by "an imperious woman."

And then there are the frauds. Yagoda notes that earlier generations of readers did not make the same distinction between fiction and nonfiction that we do now, but by the 19th century, they cared enough to object when someone presented himself as former captive of a Native American tribe, an escaped slave, or a sailor who survived a shipwreck off the coast of Africa when he was, in fact, not. The more polemically charged an autobiographical claim -- the testimony of former slaves relating the abuse they suffered while in bondage, for example -- the more likely it was to be challenged by political opponents (and defended by supporters). As controversial contemporary memoirists like Nobel Peace Prize winner Rigoberta Menchu demonstrate, an autobiographer can expect rigorous scrutiny from those who don't like what she has to say -- as well as a lot of slack from those who do.

"All autobiographies are lies," said George Bernard Shaw, and Yagoda concurs, to a degree. Pointing out that most of us can't recall the exact words of conversations we had yesterday, let alone those of many years past, he writes, "all memoirs that contain dialogue -- which is to say all recent and current memoirs -- are inaccurate." Nevertheless, this does not make them utterly false. Ideally, "the dialogue in a memoir is the author's best-faith representation of what the people who were present could have/would have/might have said." Complicating the matter is the growing body of evidence that even when people are trying their damnedest to recount the precise details of some recent experience -- when they're, say, testifying under oath in court -- they get a lot of stuff wrong, often in a way that suits their own desires and needs. Unreliable and revisionist, memory, as Yagoda puts it, "is itself a creative writer."

"Memoir: A History" offers a pleasant tour through the various manifestations of the form, with Yagoda pointing out landmarks and dropping the occasional witticism or pithy insight. Over there are the memoirs of religious faith and conversion -- a major category -- and over here are the sensational death-row confessions by criminals looking to parlay their notoriety into one final payday. Eighteenth-century women of easy virtue wrote titillating accounts of their lives and loves, an especially profitable enterprise if you charge former clients to have their names kept out of it. There was a brief vogue in the 19th century for anti-Catholic "exposés" of convent life, supposedly written by former nuns. There were the travel and adventure memoirs of the early 1900s, written by people like T.E. Lawrence, and, long before Studs Terkel, a spate of first-person oral histories recorded by journalists and relating the stories of ordinary citizens and workers. A particular breed of "light autobiography," humorous and nostalgic depictions of American family life, flourished in the mid-20th century, but nowadays hardly anyone reads such titles as "The Egg & I," "Cheaper by the Dozen," and "My Sister Eileen." (Although the branch library of my childhood was full of these books, and I loved them.)

With the 1960s, this brief sunny interlude of what Yagoda calls "normative memoirs" ended in a blaze of fiery truth-telling, led by African-Americans, whose literature is founded in the urgent need to testify to the reality of black lives. Yagoda persuasively argues that there's a line of direct descent from, say, "The Autobiography of Malcolm X" to "Girl, Interrupted" and the hundreds of memoirs about child abuse, incest, mental illness, addiction, cancer and other traumas that began to appear in the 1980s. The political imperative to "speak truth to power" segued into a widespread belief in the healthful effects of defying decorum to talk freely about what were once private horrors. (Interestingly, Yagoda notes that the "extreme misery memoir" is now even more popular in the U.K. than in the U.S., "a particular and somewhat alarming British taste, like Marmite or mushy peas.")

For the most part, it's hard to quarrel with "Memoir: A History," but Yagoda does manage to slip a little controversy bait into an otherwise reasonable book. Behind much of the current kvetching about the memoir boom lies the impulse to protect the artistic supremacy of the novel. So when Yagoda writes,"fiction has become a bit like painting in the age of photography -- a novelty item that has its place in the Booker Prize/Whitney Museum high culture and in the genre-fiction/black velvet-Elvis low but is oddly absent in the middle range," he's inviting trouble and knows it.

It's true that material that writers would once have worked into fiction -- classic autobiographical first novels like "The Bell Jar" or James Agee's "A Death in the Family," for example -- will now more likely be presented as memoir. But whether such novels once occupied the whole extent of the middlebrow fictional spectrum between, say, a Booker Prize winner like Ian McEwan's "Atonement" and a Tom Clancy thriller is debatable. Besides, "Atonement" was as successful as any memoir (and more successful than most). "The Lovely Bones" sold as well as "Eat Pray Love," and probably to the same readers. Yagoda's statement about memoir usurping the novel is the sort of thing people worried about the future of literary fiction seize upon in their frequent moments of hysteria, but -- like a lot of the dicey memoirs he writes about -- it has a tenuous connection to actual fact.

More truly provocative is Yagoda's assertion that the rise of memoir shows how "authorship has been democratized"; everyone has a story to tell and who better to tell it than the one who lived it? We put less faith in expertise and objectivity, and more in what's spoken "straight from the heart." Furthermore the authenticity of a first-person account of a true story will, in many readers' minds, make up for a lack of the literary finesse required in fiction. James Frey could not find a publisher for the preening, bombastic "A Million Little Pieces" when he first attempted to sell it as a novel; marketed as a memoir, it was a hit, and continued to sell well even after he was publicly disgraced for making up many of the book's more melodramatic events.

In any given year since the blossoming of mass literacy in the 19th century, the selection of new books on the market consists of a handful of excellent works, a more sizable swath of total dreck and an ocean of the merely OK. For the past century and a half, the vast majority of merely OK authors have written novels, on the understanding that this is what serious writers ought to do. Readers liked the results more or less depending on the subject matter or style, but in general there was not a lot to distinguish these novels from each other, and in a few years they were utterly forgotten. This is the fiction that could now be losing ground to the memoir.

Is this necessarily a bad thing? As Yagoda writes, the memoir has an advantage over the novel in that "it is easier to do fairly well." For mediocre writers, it is indeed a godsend, offering them not only a greater chance of publication but also a greater likelihood of producing a decent book. Yagoda calls this "a net plus for the cause of writing." The one thing the memoir does lack is the literary novel's aura of art, but a lot of the people now writing popular memoirs wouldn't have been able to produce great novels anyway, and might have broken their hearts trying. Now, at least, they have a chance of winning some readers. Still, there's a sense that the bar has been ignominiously lowered.

The celebrated Bosnian-American novelist Aleksandar Hemon spoke for the uneasiness caused by this state of affairs when, earlier this year, he told BookForum, "I hate confessional memoirs ... Literature, to my mind, starts from some sort of personal space -- and then it has to go beyond that. Whatever experience you may have had, whatever stories you might have to tell about yourself, they have to be transformed into something that's meaningful beyond yourself. And because it's transformed at some point, it stops being about you. The person in my fiction is not my life, so we can talk about it. If it were my life, what would you have to say about it? Memoir is not subject to interpretation. That is antithetical to literature. Confessional space is solipsistic: I'm the only one there, you don't get to enter."

In fact, the opposite is the case. It's precisely when we are conscious of fictional characters as the invention of a literary author that they seem inert and fixed -- solipsistic -- to many readers, who usually don't feel entitled to quibble with the exalted creator about his choices. By contrast, the characters and events in memoirs are often, like real people and events, the subjects of energetic controversy, which makes them seem more alive. Who was to blame for the author's divorce? Was he justified in his rejection of 12-step programs? Was her mother bipolar, and how might her life have been different if she had been medicated? People who have read the same memoir can talk about this stuff for hours. The real world, after all, is available for an infinite range of interpretations, while we tend to see the products of the literary novelist's imagination as admitting only a few, and most of those are likely to be detached and aesthetic rather than moral and immediate.

Both of these notions are illusions, of course. It's not the made-up aspect of literary fiction that makes it seem marmoreal and remote -- otherwise, millions of people wouldn't be discussing the entirely fictional characters on "Lost" or "Mad Men" around the water cooler or in online forums. Children and adults would not have massed in bookstores at midnight to buy the latest Harry Potter installment. Those fictions -- TV shows and children's books -- have, like the memoir, not yet acquired the official status of Art. As long as they remain at least a little disreputable, they are our size, and lovable. But make the memoir respectable, clear it of all the charges against it -- of vulgarity and commercialism and calling too much attention to itself, as well as of fraud -- and chances are that sooner or later we'll get bored of it, too.

Shares