In third grade, my teacher announced that we would be celebrating St. Patrick’s Day by wearing green hats and giving ourselves fake Irish names. And so was born that great Celtic patriot Francis McLam, and next to me was the even-more-improbable sounding Mike O’Gotkowski. Our friend Michael O’Reilly was now — in the face of all this Irishness — no longer sufficiently Irish, and so he became Michael McO’Reilly. It was my first inkling of how strange Americans are about traditions on St. Patrick’s Day, a feeling reinforced years later by watching people of all races and ethnicities pretend at Irishness by getting plowed on green beer and painting themselves like leprechauns. But despite all this, maybe the most straightforward of St. Patrick’s Day celebrations, eating the corned beef and cabbage, is secretly one of the strangest.

“My Irish family never ate corned beef,” the letter began. I’d just written a story about new immigrants in Queens, called “Where Curry Replaced Corned Beef and Cabbage,” and a reader was gently protesting my mention of that stereotypical dish.

“My grandmother was perplexed that Americans associate corned beef with being Irish. In Ireland, most people ate pig. Lots of bacon, lots of sausage (lots of trichinosis).

…Corned beef was made popular in New York bars at lunchtime. The bars offered a ‘free lunch’ to the Irish construction workers who were building NYC in the early part of the 20th century. But there’s no such thing as a free lunch. You had to buy a couple of beers or shots of whiskey to get that free lunch. And that’s how corned beef became known as an ‘Irish’ food. My grandmother hated the stuff and wouldn’t allow it in her home. I myself first tasted corned beef when I was in my thirties at some non-Irish-American person’s ‘St. Paddy’s Day’ party.”

Dismayed, I sent that letter to a friend from Dublin. “Every word of that post is pure gospel,” she wrote back. “We NEVER eat corned beef and cabbage. We mock Americans and their bizarre love of that ‘meat’.”

Irish people denying corned beef and cabbage! Shocking! Like if Italians denied pizza and Chinese denied General Tso’s Chicken. Wait, they have? OK, well, let’s move on.

Theories abound as to why Irish Americans wear the corned beef and cabbage mantle. There’s the “Irish drink a lot in bars” theory, above. And then there’s the “they got to New York and couldn’t find their beloved bacon, so they started eating their Jewish neighbors’ corned beef instead” theory.

First, let’s settle one thing: Ireland knew how to rock the corned beef. According to Irish food experts Colman Andrews and Darina Allen, corned beef was, in fact, a major export of Cork from the 17th century, shipping it all over Europe and as far as the sunny British West Indies, where they still love their corned beef in cans.

Most of the Irish who came in massive waves to America during the Potato Famine in the late 1840s were from around Cork, so they probably knew corned beef well enough. But, as the historian Hasia Diner argues in “Hungering for America,” they may have been trying to forget altogether what they were and weren’t eating back in Ireland.

By the 1900s, she writes, there was a movement in Ireland to revive Irish culture, flagging after decades of emigration and centuries of English colonial rule. The Irish were embracing their language, their dance and music, but there was little mention of traditional cuisine. “Food lay at the margins of Irish culture as a problem, an absence, a void,” Diner writes. “The Irish experience with food — recurrent famines and an almost universal reliance on the potato, a food imposed on them — had left too painful a mark on the Catholic majority to be considered a source of communal expression and national joy.”

While many Irish Americans found livelihoods running inns and groceries, few sold any food they called “Irish.” Her research turns up many early Irish American St. Patrick’s Day banquets that celebrate Irishness with menus tricked out with “harps, shamrocks, Celtic-style lettering, Celtic crosses, all potent reminders of Ireland. [But] the Irishness of the food amounted to little.” The dinners featured French-sounding dishes, like “Cotelletes de pintades a le Reine.” Even potatoes got washed through the de-Irishizer: “Pommes de terre persillade,” which anyone could tell was just boiled potatoes with parsley.

So there was a culinary hole in the culture of the Irish immigrants, one partially filled with that great filler of food holes: bacon.

“Only ‘Irish bacon and greens’ appeared yearly as a food meant to convey the homeland. Bacon may have been the perfect food vehicle to link their Irish and American selves. Americans, on the one hand, had been savoring [exported] Irish bacon for a century or more. On the other, Irish farmers who had long produced massive amounts of it, only began to regularly eat it themselves by the end of the 19th century. By the time these menus were being printed up, bacon had become a ubiquitous item on the dinner tables of modest Irish farm families. Hence, unlike potatoes, bacon carried no stigma of shame. It rather announced the successful progress of Ireland…”

So why aren’t we all getting sloshed on green beer and eating bacon and cabbage today? The problem, according to Marion Casey, clinical assistant professor of Irish-American studies in the Glucksman Ireland House of New York University, was perhaps that the Irish loved their pig a little too much. (Yes, food blogosphere: This is apparently possible.)

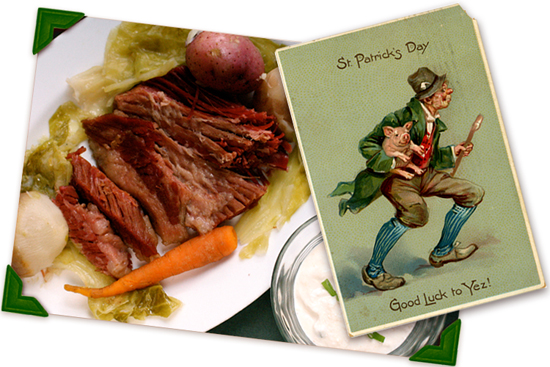

Many farmers in Ireland raised pigs for sale to help pay the rent, but somewhere along the line in America, that tradition mixed with the bitter cocktail of prejudice and xenophobia to turn it into a slur: “Paddy with his pig in the parlor.” The phrase may have had rhythm, but it wasn’t pretty. (I mean, the postcard in the picture above is hardly flattering, now is it?)

By the 1910s, pigs were all over St. Patrick’s Day cards and novelties, including a game called “Pin-the-Tail-on-the-Pig” for kids. “Irish Americans,” Casey wrote me in an e-mail, “vigorously protested an alignment of their ethnicity with an animal that carried all sorts of connotations about dirt and disease.”

But “by this time,” she continued, “much of Irish America had moved beyond mere survival. They ate pork and beef, salted or not. It was just as easy to claim corned beef as their choice for holiday meals as it was to claim pork. When the latter became stigmatized, one became preferable to the other.” Of course, by this time, old memories of the corned beef back in Cork may have bubbled back to the surface. In 1960, we had the first St. Patrick’s Day card reference to corned beef and cabbage, and before we knew it, little Chinese boys in the suburbs would be pretending to be Irish in the middle of March.

But is that any weirder than Irish people pretending to be Irish? Each of the experts I spoke to would agree on one thing: that there isn’t really a point in arguing about authenticity, because authenticity always changes. People make up traditions all the time, so why is it that only traditions old enough for you to forget how they got made up in the first place are the “real” ones? This year, instead of corned beef, I’m going to serve bacon and cabbage stir-fried. But I’m keeping my name.