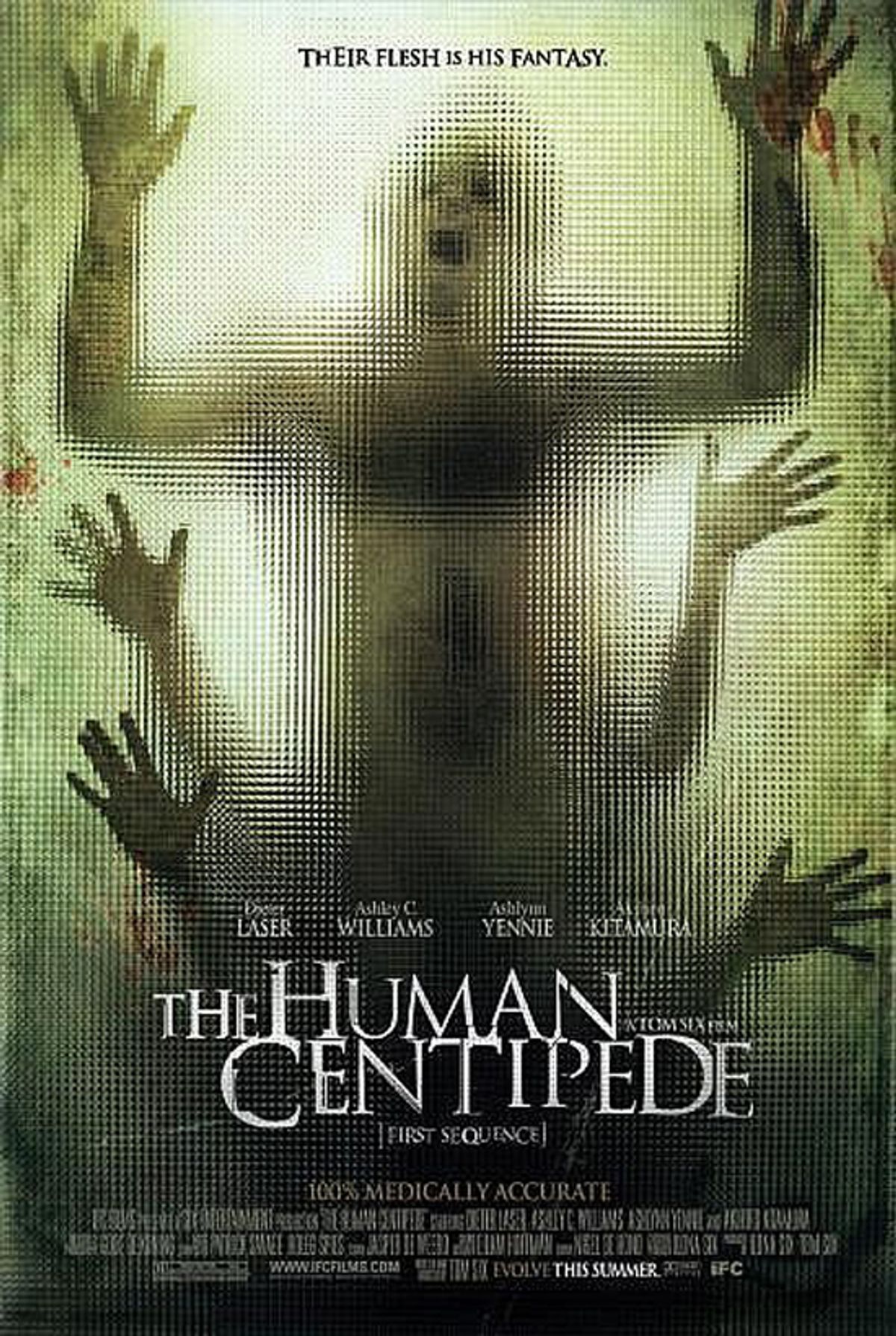

Horror movies have always been violent, but in recent years, it seems, they've reached gruesome new lows. The past few years, the "torture porn" trend -- as exemplified by the many "Saw" films -- has continued unabated. A recent film, "The Human Centipede," centered around a German surgeon trying to assemble the gastric systems of three tourists, and this September, one of the most notoriously violent horror films of the '80s, "I Spit on Your Grave," will be getting its own slick remake. (The movie, in which a city writer visits a lakeside home, is gang raped and takes violent revenge on her rapists with, among other things, an outboard motor, was described by Roger Ebert as "so sick, reprehensible and contemptible that I can hardly believe it's playing in respectable theaters.")

But it's precisely the extreme nature of horror that makes it such a lightning rod for debates about hot-topic issues within American culture -- like racism, women's rights, consumerism and sexuality -- along with broader issues of morality. A new book, "The Philosophy of Horror," a collection of essays from academics, edited by Thomas Fahy, the director of the American Studies Program at Long Island University, addresses the latter, with contributions about the hidden messages of everything from "The Birds" to "Hostel."

Salon spoke to Fahy over the phone from the Upper West Side of Manhattan about the rise of "torture porn," the latest slew of horror remakes, and the bizarre appeal of watching people get chopped up by maniacs.

Why have horror movies been such a fertile ground for social and political commentary over the last few decades?

On the most basic level these are films about mortality and the immediacy of the choices that we make in our lives and their consequences. They deal very directly with life and death. They invite us to think about the types of choices we make as individuals and as a society and the implications of those choices. Historically, horror movies surge during times of crisis. Think of the monster films during the Great Depression, and the horror and science fiction films of the 1950s, where the monster was a metaphor for the communist threat. More recently, horror has been addressing how we feel about war, about terrorism, the economy and the state of the world. It surges at times when we feel a lot of collective anxiety about things. I think that can be comforting because they lay out the world in black-and-white terms as good vs. evil.

Clearly the so-called torture porn genre isn't letting up. The most recent film to get a remake is "I Spit on Your Grave." The original caused outrage, most notably from Roger Ebert, when it was released because of its strong torture elements.

It reminds me of the recent remake of "Last House on the Left." In both cases, the originals are so disturbing and so violent. I do think there is a general sense in these films that we live in a cultural moment right now in which there is a great deal of violence and lawlessness and immorality. Retribution is part of the appeal of this, especially if we feel that we’re living in a time where there are people committing atrocious crimes -- including CEOs of hedge funds.

I have heard a lot of people in their discussion of these remakes argue that this emphasis on torture is a passing fad, but I actually don't think that's true. Critics tend to ignore the fact that these films are part of a very long history in which torture and public executions are part of popular entertainment, from gladiator battles to the Inquisitions to public executions in 18th century France to lynching in the U.S. in the 19th and 20th centuries. The question becomes, Why are people watching them right now?

So why are we watching them right now?

I think we’ve been talking about torture in this culture a great deal recently and these films raise a very clear question: Is it ever permissible to torture someone? It’s a hell of a lot different thinking about that when you're watching somebody torture somebody, in all of its ugliness, on-screen than when you’re watching the nightly news.

What I find interesting about them is that they're not films about mutilating and torturing women -- in the "Last House on the Left" remake, one of the torturers actually is a woman. And "Hostel" was raising a lot of really provocative questions. The protagonist who is able to escape the torture facility -- in which rich people pay to torture European backpackers -- had a different price charged for people from different countries and the most expensive people to torture are Americans. That speaks to anxieties that we have as a country.

What's the most significant difference between the original and the remakes of these '70s horror movies?

The remakes are a lot darker. When you think of "Nightmare on Elm Street" in the '80s, that is a scary movie; but the campy, ridiculous humor of it, which is part of the fun of the film, is absent from the remake. It's similar to the new James Bond films, and if you compare the "Batman" of the '80s to the current one, they couldn’t be any more different. In our current cultural moment, that kind of humor is not going to speak to people.

Well, it seems easier to joke about people dying when the general cultural mood is fairly upbeat.

When George Bush announced that there was an "axis of evil," there was a hope that you could still divide the world up into compartmentalized terms. Clearly such dichotomies have proven to be so false, and the situation to be so much more complicated, that films today and books today can't present things in those kind of terms.

The message of most of the horror films I've seen has been very conservative -- don't do drugs, don't drink, don't have sex, or you'll get stabbed to death by a maniac.

There is this politically conservative undercurrent that does seem to operate in a lot of horror films. But I think it balances out in interesting ways. The same slasher films that punish teens for drinking always have a young woman who challenges the notion of women as victims. Even if you go back to "Psycho," the protagonist, a woman, gets killed halfway through the film, but she's also an assertive woman who steals money; she stakes control of her destiny. And who steps in to fill in for her when she’s killed? Her sister. That’s a film dominated by strong female characters.

Do you still think that's true in the age of torture horror?

I think there's been a shift. The message is less about doing drugs and drinking than it is about moral questions about justice and right and wrong. These recently incredibly popular "Saw" movies -- all 5,000 of them -- are killers with moralistic agendas. They are out torturing people that they feel embody sinfulness because we live in a society so corrupt and so infused by criminality and violence that we’re apathetic, and then they use extreme violence as part of their message.

What's the most interesting horror film that you've seen recently?

I think "Paranormal Activity" taps into a couple of things that are an active part of American pop culture right -- reality television and a fascination with voyeurism. With TV shows like "Housewives of NYC" or "Jersey Shore," we know that there are editors and tons of people shaping and crafting it, but they're doing it in such a way that people feel they have honest, intimate access to the people on the screen. I think this film tapped into that.

The horror genre is constantly trying to make itself fresh by blurring that line between fiction and reality and legitimately shake you and scare you. I think that film was able to do that because it embraced that kind of reality TV culture.

It might also be that Americans are just tired of watching slickly commercial films.

When Americans remade "The Grudge," for example, they took out the more experimental structure and simplified the narrative to make it more palatable to a mainstream audiences. At the core, horror films are about making money in America. The remake of "Nightmare on Elm Street" didn't get that much buzz, and I wonder if it's because people aren't craving that kind of slick Hollywood horror film right now.

What draws you to watch horror movies?

I think at its most basic level, people like horror films because they’re an outlet. We’ve all felt anger, had negative thoughts, behaved recklessly at one time or another. We all have these characteristics or qualities in us somewhere that horror films tend to literalize or give extreme examples of. In some ways it’s a fun outlet for exploring the darker angels of ourselves. It’s an outlet for those things. Like a roller-coaster ride, it can be thrilling and fun and you feel like you confronted a certain fear and you mastered it -- once it’s over.

Shares