"Inside Job" is an angry and elegant new documentary from entrepreneur-turned-filmmaker Charles Ferguson, who took on the mismanagement of America's war in Iraq in his Oscar-nominated "No End in Sight." It might well be the most important film you see this year, and the most important documentary of this young century. In clear, ruthless and specific detail, Ferguson explains how the ongoing financial collapse that began in 2008 was itself caused by the criminal greed of the global financial elite that ordinary citizens had (unwisely) trusted, empowered by government deregulation and by the viral spread of rapacious free-market ideology.

Angry and elegant is an unusual combination, and as a wealthy, well-connected policy wonk who makes expensive movies aimed at a large audience, Ferguson has gotten a mixed reception from the documentary world and from film critics. But "Inside Job," which was the smash hit of last spring's Cannes Film Festival and reaches American theaters this month, has made me a believer. Ferguson is here to tell the world that the crisis that has wiped out trillions of dollars in wealth, thrown millions of people out of work and out of their homes, and further widened the global gulf between rich and poor was no accident. It was a crime.

Ferguson, who made millions in the software industry of the 1990s and has worked as a scholar or lecturer at MIT, University of California at Berkeley, and the Brookings Institution, is definitely no left-wing bomb-thrower or closet Marxist. But he plays one in the movies, you might say. He is both more pragmatic and more intellectual than most people in the film world, which makes him an unusual and challenging interview subject. Here's what I wrote about Ferguson and "Inside Job" from Cannes last May (edited for length and clarity), followed by an excerpt from our conversation.

"Inside Job" offers a lucid and devastating history of how the crash happened, who caused it and how they got away with it. Furthermore, Ferguson argues, if we don't stop those people -- preferably by removing them from power, arresting them and sending them to prison -- they will certainly do it again.

With a damning parade of interviews, images and public testimony, Ferguson illustrates how, by the time the 21st-century bubble reached its peak around 2006, the financial industry had ridden 20-plus years of manic free-market deregulation and neoliberal fiscal policy from one crisis to the next, surfing a rising tide of greed and corruption. There are several people in this movie, prominent among them former George W. Bush adviser Glenn Hubbard and Harvard economics chairman John Y. Campbell, who must be very, very sorry that they agreed to talk to Ferguson. Some critics have complained about Ferguson sandbagging such clearly unprepared subjects -- but, no, I'm sorry. There are some people who richly deserve public humiliation, and it's totally gratifying to see them get it.

I met Ferguson, a lean, intense fellow in his mid-50s, for a post-breakfast conversation in the oddly apposite setting of a restaurant overlooking the Cannes beachfront.

Your film and Oliver Stone's "Wall Street" sequel tackle approximately the same subject matter. He's built his movie around the financial term "moral hazard." What you show in the film -- a situation where we've deregulated the entire universe and created a strong disincentive for people to behave ethically -- isn't that the ultimate illustration of moral hazard?

Yes. Deregulation permitted, allowed and created an industry where moral hazard was the norm and the universal condition. And people took advantage. When there is moral hazard one usually finds that people take advantage and in this case a whole industry took advantage.

Do you think the deregulation of, say, the Reagan years and thereafter started from a pure ideological position? Or was it influenced from the beginning by the financial firms who had a great deal to gain?

The latter. Well, it was a combination of the two; it wasn't just that. It was both of those things. And you saw in the '80s for the first time the beginnings of this unholy alliance between the financial services industry and the academics who pushed the free-market ideological-intellectual agenda. We talk a little bit about that in the film. About the fact that Charles Keating paid Alan Greenspan to write him a consulting letter, for example. We actually have a lot more material on that that was in a rough cut of the film, which I took out for reasons of length and I have many regrets about.

One extraordinary thing that we have is a filmed interview, sometime in the late 1980s, with Sen. William Proxmire, who at the time was the chairman of the Senate Banking Committee. He says in an extremely blunt, direct way: My committee was bought off by the savings and loan industry, which led to the passage of the Garn-St. Germain Act of 1982, following which there was this extraordinary wave of criminality. So the money was there from the beginning -- both money and ideology. Over time I think the money has come to be even more dominant. Now, of course there are people who still believe in free-market ideology, but that's not the core of what's going on; the core of what's going on is the money.

This may be forcing a parallel, but here's what occurred to me: At the beginning of Marxism-Leninism, the leaders who believe in what they're selling. We can assume that Lenin and Trotsky believed that they were changing the world for the better, history was on their side, and so forth. Maybe Stalin did too, at first. By the end of the Soviet state, you have a completely corrupt environment in which nobody, including the leadership, actually believes in the Communist future. I wonder if we're seeing a speeded-up version of that same ideological decay in the world of free-market capitalism.

I think that's an extremely accurate and perceptive analogy. And it's also a very disturbing one. The idea that the United States is being taken over by this utterly cynical group of people who know that this is a rigged game and just kind of give it lip service. I think that there's a lot of that. The United States has changed over the past 30 years. America has changed. And it really is time I think for the American people to unchange it.

As you demonstrate, these guys have taken advantage of the way Congress works to fund candidates, control the process and control and actually write legislation. It's not quite enough to throw the bums out. We have to remake the political process as well.

It is an extremely daunting problem, but I wouldn't say that I'm entirely pessimistic about it. There have been times before in history where a country, a government, got taken over by some bad people who did some bad things and the population threw them out. I think there's a reasonable analogy in that regard with Watergate. There's a situation where one could have said -- and many people did say -- "Look, how are you going to get rid of the president? How are you going to get rid of a whole administration?" We did.

Just because the system has been taken over doesn't mean that that always has to be the case. I am reasonably optimistic that over time the American people are getting angrier about this. That's happening now. Will they get angry enough? Will there be enough action? We don't know yet.

One manifestation of that, I suppose, is the Tea Party movement. That represents populist anger, at least in theory. But if it's just incoherent, xenophobic rage that's ultimately in thrall to the Republican Party, that's not likely to disempower the financial elite.

Situations like this are dangerous and unstable. The Great Depression gave us Franklin Roosevelt, but it also gave us Adolf Hitler. When a system is under stress and things get extreme and people are angry, they call for reform but they are also vulnerable to exploitation, and that is disturbing.

In your film we see recent congressional testimony, from April 2010, in which Goldman Sachs executives discuss selling securities to major clients, such as pension funds, that they themselves were betting would fail. How does someone in that world justify that behavior to themselves?

In a number of conversations I've had with bankers, I've been struck that they find it surprising that somebody would raise ethical questions. They don't find it surprising that legal questions could be raised. "Could I get in trouble?" That's a discussion they're very familiar with. But, "Is this right or wrong?" That's not a discussion they have often.

As you depict it, this industry has completely absorbed the idea that there is no right and wrong, there's only making money. Maybe I'm naive, but that 's pretty shocking.

It was shocking to me. It's not like I didn't know that there were greedy people in the financial world. When I started making the film I knew that there had to have been some bad behavior, but I had no idea that on a very large scale people had designed securities with the intention of selling them and gambling on their failure. I was stunned when I discovered it.

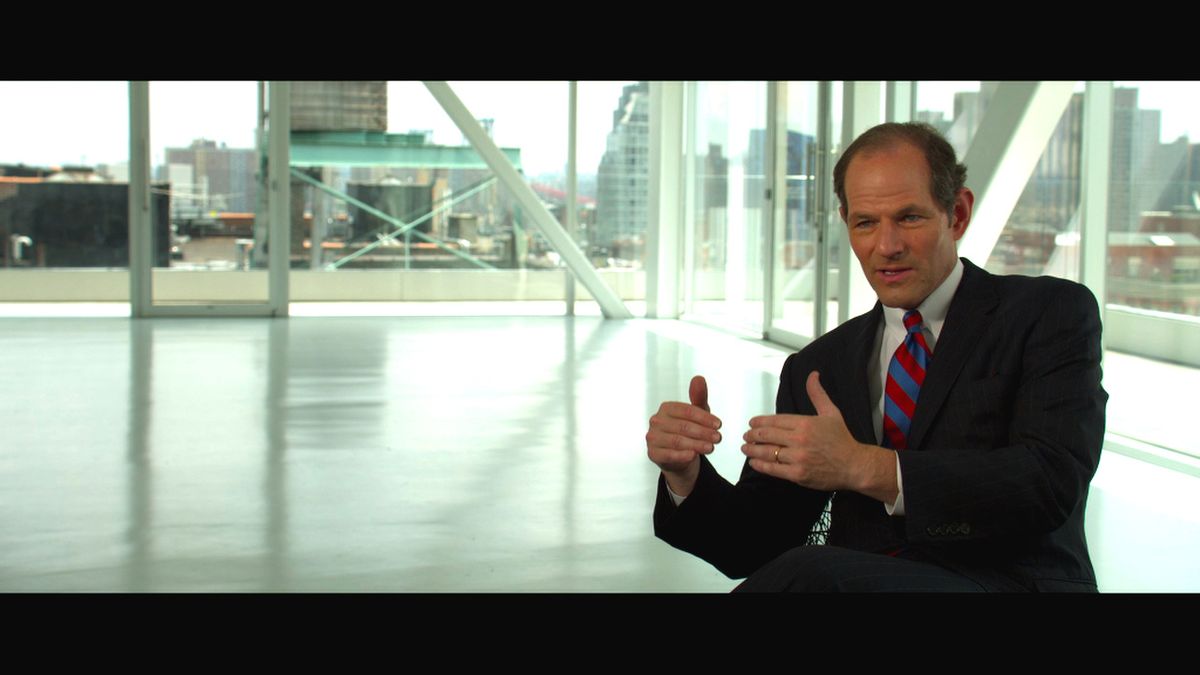

You have a fascinating conversation with Eliot Spitzer where you suggest that the financial sector has become an enormous criminal enterprise. You yourself were a high-tech entrepreneur, and what he says about the differences between the two worlds is very interesting.

I asked him about this striking, distinctive, unique level of criminality in finance, which is not restricted to the behavior that led to this crisis. There have been many other examples of criminal behavior in finance. There are now three major banks that have been convicted of large-scale money laundering for Iran. Just a few days ago, ABN AMRO signed -- I love this charming phrase -- a "deferred prosecution agreement" and agreed to pay a $500 million fine because they did it too. So it's an industry that has a very high level of criminality. It has become, I personally think, a criminal industry.

I asked Spitzer about that: Why this industry? I have some experience with high technology and the same thing doesn't happen. He agreed with me, but we actually didn't show his full answer. His full answer was: Look, high technology is an industry where you create money by doing something different. In contrast, finance is really kind of zero-sum. It's a trading game, it's a gambling game. There's a relatively fixed pool of money, but there's a lot of money and the way you make more, as a banker, is by making sure that someone else makes less. It's really hard to keep that industry ethical without appropriate legal and regulatory controls. If Intel made microprocessors that blew up the computers they're in, Intel would go out of business. The same is not true for financial services. It was a very sobering moment.

You cover the question of executive compensation in the film, the insane salaries and bonuses these guys take home. Is that a largely symbolic question, or does it speak to the corruption of the system?

Oh, it's an extremely real question. First of all it's a very obvious symptom and example of the corruption of the system, but it's much more than that. It's also systemically important. These people do these things because they can make money doing them and get away with it. And if they couldn't, they would behave differently. If there's a place in the world where you can make a billion dollars by being a criminal, that place is going to attract criminals. And if you have a system that is appropriately regulated so the only way that you can make money is by doing something worthwhile, you are not going to attract criminals to run that industry.

We now have a situation where the way that you can make the most money is by doing criminal things. And you get away with it. You can even destroy your own company. In some cases, destroying your company is the way that you make the most money. And that's bad. Personally, from the experience of researching and making this film, I think that legal controls on the structure of executive compensation are a very important part of fixing this.

By the way, from the experience of starting my software company, I can tell you that people in high technology are extremely aware of this. I dealt with the venture capital firm that invested in my company and they were extremely clear. They said: You're going to get a salary. It's going to be $100,000 a year. It's never going to go up. You will never get a bonus. You will have no outside activities of any kind. You will not make a dime doing anything else. Your stock will vest over five years. And if you want to make money, you make that stock worth something. Period. It's really simple.

"Inside Job" opens Oct. 8 in New York and Oct. 15 in Los Angeles, with wider national release to follow.

Shares