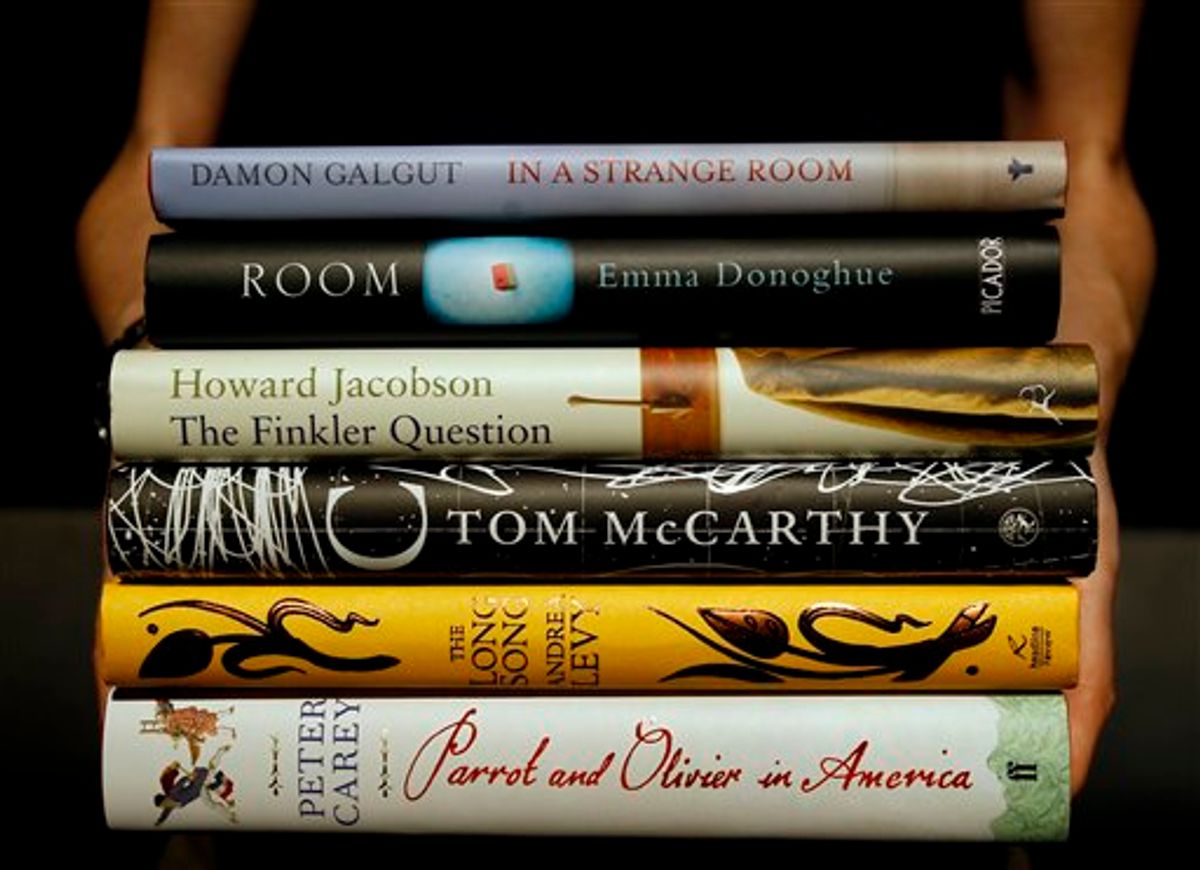

By the time Howard Jacobson's "The Finkler Question" won the Man Booker Prize in London last night, the bookmakers who famously place odds on the outcome had closed down betting on the favorite, Tom McCarthy's "C," due to a "suspicious" last-minute rush.

That's the Booker in a nutshell, a British prize that generates tabloidish buzz in the U.K. (they even broadcast the ceremony on TV) and commands a surprising amount of sales clout on this side of the pond. "C" has divided critics and readers; McCarthy is a one-man campaign for the revival of the nouveau roman, the strain of European experimental fiction pioneered by such writers as Jean-Paul Sartre and Alain Robbe-Grillet. People either love that idea, or really, really hate it, and despite all those dicey-looking, 11th-hour bets, it seems there just weren't enough lovers of high modernism on this year's jury.

"The Finkler Question," on the other hand, ruminates on the nature of British Judaism. Its author, despite having two previous novels on the Booker long list, has complained in the press that comic novels like his aren't taken seriously enough. He's got a point, but as someone who couldn't make it through "The Finkler Question," I'd suggest that this isn't necessarily due to what Jacobson has termed "a false division between laughter and thought, between comedy and seriousness."

Instead, while more or less everyone can agree that tragedy is sad, humor is far more dependent on individual predisposition. The corrosive satire that some readers find hilarious strikes others as repellently misanthropic. One man's whimsy is another's unbearable cuteness. Physical comedy leaves some people cold, while others complain that strictly verbal wit is too dry. And when a comic novel doesn't impress you as funny, then chances are that the whole book will seem pointless.

That said, the Booker will surely give Jacobson's reputation a boost in this country as well as in his own. Hillary Mantel was a writer's writer with a relatively small following of American connoisseurs before "Wolf Hall," last year's Booker winner and her first bestseller. As a general rule, booksellers and publishers think the Booker has a greater influence on American sales than even the National Book Award, its stateside equivalent. (The NBA shortlists will be announced today and the winners declared next month.) Despite a few blips -- "Vernon God Little," anyone? I didn't think so -- the Booker is seen as a more reliable indicator of quality. One longtime Salon reader, Toby Levy, has even made a practice of reading each year's shortlist; you can see his rankings here.

The most important factor in the Booker's success is the diversity of its judges. This year's panel included a dancer, a broadcaster and an author, as well as chair Sir Andrew Motion, former Poet Laureate and celebrated biographer. Although book people like to kibbitz about "typical" winners, most major awards, like the Booker, change their judges every year. (The Nobel Prize for Literature is the exception.) The line-up that picked Aravind Adiga's "The White Tiger" for the 2008 Booker is entirely different from the one that selected Alan Hollinghurst's "The Line of Beauty" in 2004. Nevertheless, the criteria used to select those judges has been consistent, and while even the most breathless prize-watchers seldom stop to consider such details, it's these criteria that determine the character of each prize.

The Pulitzer Prize for fiction -- the most influential of the American prizes -- is, for example, awarded by the Pulitzer Board, which is mostly composed of newspaper editors and journalism professors. However, the board selects its winner from a list of three candidates chosen for it by a panel of three jurors: usually a working critic, an academic and a fellow novelist. (Full disclosure: I served as Pulitzer juror last year.) So while the final choice tends to reflect the relatively mainstream tastes of the board (which famously rejected Thomas Pynchon's "Gravity's Rainbow" in 1974, despite strong recommendations from all three jurors), the winner is often the most accessible alternative among three candidates selected by readers with the expertise (and esotericism) of specialists.

The National Book Awards, by contrast, are chosen by panels of five judges in each category (fiction, nonfiction, poetry and young people's literature), who have "written and published works in that category." In theory, fellow practitioners are the best judges of excellence in a given form, but this perfectly plausible reasoning suffers from a basic flaw: Writers are rarely disinterested in their evaluations of their closest peers.

Authors are competitive and often envious. Even at their most scrupulous, they tend to assume that prizes exist to help writers, not readers. Readers want judges to tell them which book is the best, but as far as most authors are concerned, attention, that precious resource, ought to be more equitably distributed. The National Book Awards' reputation for erratic and even baffling choices, particularly in the fiction category (Susan Sontag's "In America," Lily Tuck's "The News from Paraguay," etc.), has its roots in the many clashing agendas that come into play when five novelists get together to name the year's best novel.

There's a lot to be said for including the civilian perspective, which is just what the Booker does by routinely bringing in nonwriters as judges -- not as the only judges, but as an essential part of the mix. The book world is perpetually in danger of becoming too insular, of speaking only to itself. A literary culture in which the only people who read novels are other novelists is neither healthy nor, ultimately, sustainable. Any literary prize that wants to be valued by a wide variety of readers must, like the Booker, be willing to return the favor.

Referenced in this article:

The Man Booker Prize home page

Shares