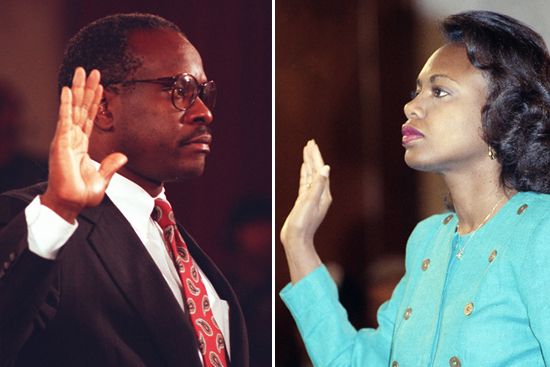

I know, I know: Looking back at Clarence Thomas’ 19-year-old Supreme Court confirmation hearings is so last week.

The story (re)exploded last Tuesday night, when word leaked of Ginni Thomas’ bizarre early morning phone call to Anita Hill, and for a few days all the ugly details that transfixed Americans in October 1991 were back on the front pages. A few days later, a former Thomas girlfriend, Lillian McEwen, finally spoke about their relationship on the record — and corroborated Hill’s claims. But then the media, as it always does, moved on, and now, to the extent anyone is still talking about it, the consensus is that we should all just let it go.

In the New York Times on Sunday, Maureen Dowd wrote that “it’s too late to relitigate” the Hill/Thomas affair, while the Washington Post’s Richard Cohen decreed on Monday that “I long ago despaired of getting to the bottom of this case, and I long ago gave up wanting to.” (Cohen also literally dismissed harassment claims against Thomas as a case of boys being boys, writing that “when it comes to his alleged sexual boorishness, he stands condemned of being a man.”)

But Dowd, Cohen and others miss the point completely: When it comes to the suggestion that Thomas sexually harassed Anita Hill in the 1980s, there’s nothing to litigate and no need to throw up your hands in confusion: He plainly did it and he plainly got away with it. And the fact that he did is plainly relevant now, given that he, his wife and his political allies are still, all these years later, intent on behaving as if they’ve been victimized.

Even before last week’s unexpected revelations, the evidence of Thomas’ guilt was considerable. Here’s what we already knew, before last week’s events:

* As Thomas’ confirmation was nearing a final vote in October ’91, an affidavit from Hill was leaked to National Public Radio’s Nina Totenberg (the source was never identified); in the document, which Hill, then a University of Oklahoma law professor, had prepared for the Senate Judiciary Committee several weeks earlier, she alleged that Thomas had repeatedly asked her out on dates and made lewd and graphic sexual comments to her when she had worked for him in the early 1980s. She made clear that the harassment had not been physical and that Thomas had never threatened her job, but said that she nonetheless felt uncomfortable and intimidated. “I felt as though I did not have a choice, that the pressure was such that I was going to have to submit to that pressure in order to continue getting good assignments,” Hill told Totenberg. She added that she had followed Thomas from job to job — first at the civil rights division of the Department of Education and then at the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission — because the harassment had briefly stopped. She was 25 years old when she first went to work for Thomas in 1981.

* Three Hill friends — Susan Hoerchner, Ellen Wells and John Carr — testified under oath that she had told them about Thomas’ conduct as it happened between 1981 and 1983. “Anita said that Clarence Thomas had repeatedly asked her out … that he wouldn’t seem to take ‘no’ for an answer,” Hoerchner told senators. “The thing Anita told me that struck me particularly and that I remember almost verbatim was that Mr. Thomas had said to her, ‘You know, if you had witnesses, you’d have a perfect case against me.'”

* Upon learning of Hill’s claims, another former Thomas employee, Angela Wright, who had worked under him as director of public affairs at the EEOC, wrote a column — not meant for publication and intended only to show potential employers at a North Carolina newspaper that she could turn around a fast and topical piece — outlining the inappropriate behavior he’d exhibited toward her. Somehow, Judiciary Committee investigators learned of the column, contacted Wright, and convinced her to sit for a phone interview, during which she detailed a pattern of harassing behavior, including an instance in which Thomas asked her what her bra size was. She was subpoenaed by the committee and flew to Washington to testify in the nationally televised hearing; the basics of her claims were reported by media outlets at the time. Her testimony would have bolstered Hill’s case — a second female Thomas underling, one who had never met or worked with Hill, accusing him of the same conduct. But the committee never called Wright, and instead simply entered the transcript of her interview into its record on the eve of the final vote. The details of her interview were buried in press reports.

* Three years later, Florence Graves, writing in the Washington Post, concluded that senators from both parties on the committee had reached a mutual agreement not to call Wright, with Republicans fearing that she’d buttress Hill’s claims and Democrats fearing that Republicans would undermine her credibility by pointing out that she’d been fired by Thomas in 1985. (Thomas told Republican Sen. Alan Simpson, one of his chief defenders on the committee, that he’d dismissed Wright for calling an employee a “faggot,” a claim that Graves and other reporters were never able to verify.)

* Rose Jourdain, who had worked with Wright under Thomas, told committee investigators that Wright had spoken to her while they worked together about their boss’ conduct. As later reported by Graves, “Though her recollections had differed slightly from Wright’s, Jourdain … had confirmed the basic elements of Wright’s account, including Wright’s anger at Thomas for what Wright had said was overtly sexist behavior. Jourdain had mentioned “comments [Wright] told me that he was making concerning her figure, her body, her breasts, her legs, how she looked in certain suits and dresses.”

* In a letter to the committee, a former aide to Thomas at the EEOC, Sukari Hardnett, wrote that many black women at the agency felt they were “an object of special interest” to their boss. “If you were young, black, female and reasonably attractive,” her letter read, “you knew full well you were being inspected and auditioned as a female.”

* In November ’94, three years after Thomas was confirmed, Wall Street Journal reporters Jill Abramson and Jane Mayer released a book, “Strange Justice,” which brought new information about the Thomas/Hill confrontation to light. As a Washington Post article described it:

“Strange Justice” uses statements from Thomas’s friends and associates to undermine Thomas’s testimony that he never talked dirty with Hill. The authors, after interviewing acquaintances as far back as his college years at Holy Cross, report that he often recounted sexually explicit films in lurid detail. Kaye Savage, a former colleague, reports that the walls of his bachelor apartment were covered with Playboy nude centerfolds. The owner of a video store near the EEOC said Thomas was a regular customer for pornographic movies.”

At his confirmation hearings, Thomas had specifically denied ever engaging in workplace discussions about pornography. Joe Biden, who had chaired the Judiciary Committee hearings, told Abramson and Mayer:

“I could have brought in the pornography stuff. I could have decimated [Thomas] with that. I could have raised it with more legitimacy than what the Republicans were doing. But it would have been impossible at that point to further postpone the hearings for more investigation into his patterns of behavior … and it would have been wrong.”

* Seven years after the publication of “Strange Justice,” the right-wing journalist who had taken the lead in trying to discredit it, David Brock, recanted. The author of “The Real Anita Hill” came clean in “Blinded by the Right” detailing his efforts to discredit Kaye Savage — whose statements to Abramson and Mayer, he wrote, represented the biggest single threat to Thomas’ credibility in “Strange Justice.”

Specifically, Brock, who had branded Hill “a little bit nutty and a little bit slutty” in a 1993 book and who had challenged Abramson and Mayer to a debate when theirs was published, detailed his coordination with the Thomas camp:

“I next set out to blow away the Mayer and Abramson story that Thomas had been a frequent customer of an X-rated video store near Dupont Circle, called Graffiti, where in the early 1980s he was alleged to have rented X-rated videos of the type that Hill claimed he had discussed with her in graphic terms. In the hearings Thomas had pointedly refused to answer questions about his personal use of pornography, other than to categorically deny that he had ever talked about porn with Hill (or with anyone in the workplace). The Graffiti story was another theretofore unknown piece of evidence for Hill’s case …”

“Now that Mark had opened up a channel directly to Thomas, I asked him to find out for me whether Thomas had owned the video equipment needed to view movies at home in the early 1980s … Mark came back with a straightforward answer: Thomas not only had the video equipment in his apartment, but he also habitually rented pornographic movies from Graffiti during the years Anita Hill worked for him. Here was the proof that Senate investigators and reporters had been searching for during the hearings.

* Wright gave an interview to NPR’s Michele Martin in October 2007, just after Thomas’ memoir was released, in which she declared that he had “perjured his way onto the Supreme Court.” On the subject of why she didn’t testify in ’91, Wright was emphatic that it had been the committee’s call:

“They wanted me to say that, please let me out of the subpoena, and then it was – you know, they wanted to portray me as having cold feet and backing out, and when we refused that deal, they finally offered me the opportunity to at least put my statement in the record. I think ultimately what happened is that they were just afraid to call me.”

All of this was known before last week, when the world learned that Ginni Thomas had placed a call to Hill on Oct. 9 asking her to apologize to her husband. Since then, we have learned more:

* In an interview with the Washington Post, Lillian McEwen, who had dated Thomas in the 1980s and who was promoted by Thomas backers as something of an alibi during his confirmation hearings, spoke publicly about her relationship with him for the first time. Now retired, McEwen said that “Hill’s allegations that Thomas had pressed her for dates and made lurid sexual references rang familiar,” as the Post put it. McEwen said that Thomas had been “obsessed with porn” and “would talk about what he had seen in magazines and films, if there was something worth noting.” She also said that Thomas would tell her about the women he worked with — even commenting to her about one’s bra size. “He was always actively watching the women he worked with to see if they could be potential partners,” McEwen told the Post. “It was a hobby of his.”

In his ’91 testimony, Thomas had told the committee to ignore Hill’s claims that he made lewd sexual comments to her:

“If I used that kind of grotesque language with one person, it would seem to me that there would be traces of it throughout the employees who worked closely with me, or the other individuals who heard bits and pieces of it or various levels of it.”

If all of this information had been known to senators in 1991, it seems clear, Thomas would never have been confirmed. As it was, he narrowly survived on a 52-48 vote. Many senators who voted for him publicly expressed reluctance, noting the “he said/she said” nature of the case.

“Both appear believable,” James Exon, a Democratic senator from Nebraska, said during the floor debate. “I intend to vote for confirmation — but without enthusiasm.”

– – – – – – – – – –

But had Wright or McEwen, who made herself available in a letter to Biden, been called to testify, or had Savage’s story about Thomas’ pornography habits been known to senators, much of that doubt would have been erased. And to those who care to review the full record now, all of that doubt has been erased. Those who say it’s time to move on may have a point, but there are several points that first need to be addressed:

* The biggest one, as I wrote last week, is that Anita Hill is owed an apology — actually, lots of apologies. She did not ask for the spotlight in 1991; her statement to the committee was leaked to the press at the last possible minute. At that point, the right turned its guns on her aggressively, challenging her motives, shredding her character and ginning up all sorts of wild conspiracy theories in order to produce some explanation for why she’d say what she was saying — other than the fact that it was the truth. Within the Senate, her chief tormentors were Arlen Specter, who browbeat her during nationally televised hearings and accused her of perjury; Orrin Hatch, who insisted that “her story just doesn’t add up”; and Alan Simpson, who notoriously spoke of how “I really am getting stuff over the transom about Professor Hill. I’ve got letters hanging out of my pockets. I’ve got faxes. I’ve got statements from Tulsa saying: Watch out for this woman.” (Simpson, by the way, is now the co-chairman of Barack Obama’s deficit reduction commission, which is due to issue its potentially explosive recommendations in December.) Richard Cohen and any columnists who continue to pretend that Hill’s testimony was anything other than credible ought to get in line, too.

* Senate Democrats dropped the ball in 1991. A second witness, Wright, was ready to testify that Thomas had behaved toward her the same way that he’d behaved toward Hill. While Republicans would have made much of the fact that Thomas had fired her, her basic claim — and the fact that another ex-Thomas employee told investigators that Wright had spoken with her about Thomas’ conduct before she was dismissed — would surely have bolstered Hill’s credibility. Back in ’91, long before he recanted, David Brock even wrote that Hill would have been more believable if a second woman had come forward. Wright has made it clear that she was ready to be that second woman. Democrats should have insisted on it.

* The lack of serious follow-up in the media, for nearly two decades, has been shameful. Mayer and Abramson did a commendable job demonstrating that Thomas — contrary to the ardent claims of his defenders during the ’91 hearings — was absolutely capable of the conduct Hill described. Given the abuse Hill took from Republicans and commentators, the revelations in “Strange Justice” should have prompted an aggressive reexamination of the ’91 hearings by the press. Instead, while the new details of the book were reported, most news coverage at the time insisted on giving equal time to Thomas’ defenders — most notably, David Brock. After a week or two of coverage, they dropped the subject altogether.

* The implications of Thomas’ confirmation were lasting. Since joining the court, Thomas has been a reliable conservative vote, key to the 5-4 decision in 2000 that made George W. Bush president. Had Thomas been rejected, George H.W. Bush might have nominated a far less strident ideologue — one more akin to his first high court pick, David Souter, who voted the other way in Bush v. Gore.

* Thomas and his wife, Ginni, are best understood as components of a conservative political machine. Thomas won his spot on the court thanks to a smear campaign organized by the right and aimed at Hill, and since joining the court, he has voted in the right’s interest in virtually every major case. In interviews and in his ’07 memoir, he has consistently presented himself as a victim of liberals and the mainstream civil rights community and has labeled Hill a “combative left-winger.” Thomas is one of six public figures whom job applicants to the Heritage Institute are asked to rate; to conservatives, reaction to his name represents an ideological litmus test.

Ginni Thomas, meanwhile, is a Tea Party activist who founded a group, Liberty Central, dedicated to dismantling much of the Obama administration’s agenda. She even signed a memo declaring the president’s healthcare reform plan “unconstitutional” — an issue that her husband may be called upon to help settle. As Dahlia Lithwick put it, “She and her husband long ago passed a point at which they worry about how they will be portrayed in the mainstream press. They stopped reading it years ago. They both live in a world in which the facts of Hill v. Thomas don’t matter. There are no facts. There are just ‘our’ beliefs and ‘their’ beliefs, just as there is ‘our’ media and ‘theirs’ and ‘our’ Civil War history and ‘theirs.'”