The night before my planned interview with Nora Ephron, I sat before the TV watching our probable new speaker of the House, John Boehner, fawn and burble over his newfound success. Something gnawed, a prickly déjà vu. It wasn't until the next day, on my way back to the office after talking with Ephron, that I realized I had been thinking about a famous line from Ephron's "Heartburn," which popped up immediately when I went searching for it: "Beware of men who cry. It's true that men who cry are sensitive to and in touch with their feelings, but the only feelings they tend to be sensitive to and in touch with are their own."

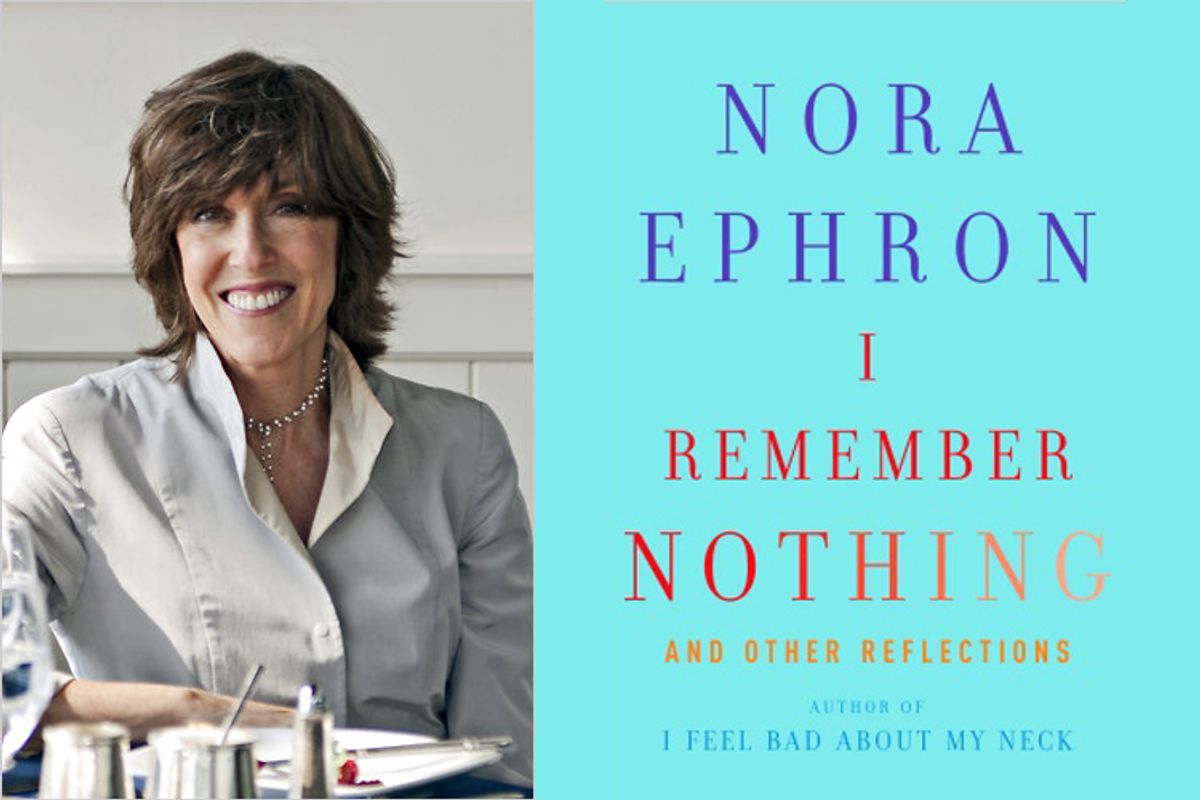

Ephron is like that. After nearly 50 years as an author, screenwriter ("When Harry Met Sally," "Silkwood"), director ("Julie & Julia," "Sleepless in Seattle"), her cultural influence is so elemental you're not always even aware of it; she's like hydrogen. But what makes her new book of essays, "I Remember Nothing" -- along with its predecessor, the best-selling 2008 collection, "I Feel Bad About My Neck" -- such a particularly big deal is not just that Ephron (who, full disclosure, I know a little socially) is a defining cultural voice, it's that she's now frequently tackling subjects -- the infuriating inevitability of getting old, and facing death -- without the gauzy sentimentality or spiritual superiority we're used to from others.

In her new collection, Ephron writes movingly about her love of journalism, and takes us through a riveting account of her rise from a wildly misogynistic Newsweek and through a rollicking New Journalism. Ephron remains a journalistic pioneer, and will be leading the Huffington Post's forthcoming section devoted to a subject, divorce, that she's been inextricably linked to since "Heartburn," her roman à clef about her failed marriage to Watergate great Carl Bernstein. There's an essay on divorce in "I Remember Nothing," as well as short takes that touch on another favorite Ephron subject, food (chicken soup, egg whites, those infernal French dessert spoons). But the power of these essays often comes from a voice clearly looking back at a riveting life with a clear-eyed wisdom and, at times, twinges of regret.

Salon spoke with Ephron at her New York apartment last week.

We're trained to talk about getting old and facing death by also talking about faith, but you're an atheist.

I said in the book that it would be helpful to believe in God. It would be helpful, but I certainly know I'm not going to be one of those people with a deathbed conversion.

Have you felt any of that tug as you've gotten older?

To faith?

Yes.

No. No, no, no. No, that would be ludicrous.

It's common, though. You must have known people who've been lifelong atheists or agnostics ...

It's entirely possible that I know people that that's happened to, but they don't spring to my head.

I was thinking about this last night as I watched the elections returns come in, the endless babble about how angry people were, and I have such a sense of how insulated we are in New York City from whatever is going on out there. We really don't have a clue. And every so often I'm with a group of people and you just run out of things to say and I say, "How many people believe in God?" In fact, the way we play the game is you have to guess how many people at the table believe in God. And it's always more than I think it's going to be. I'm always a little surprised that it's even three out of eight.

Do a lot of people hedge?

Yes, they do. "I believe there's something." They do that. But the short answer to your question is no.

Well, one of the really powerful chapters of your book is a simple listing of things you'll miss when you're dead. It's incredible to read, because I don't think many people really go there; it's uncomfortable. But obviously, you have to have some awareness after you die to actually miss something.

Well, of course. But there's nothing wrong with knowing what you're going to miss beforehand so you have quite a lot of it before it's over. I mean this is one of the worst things I remember clearly when my friend Judy -- whom I keep writing about because it was so devastating -- was dying. She had tongue cancer. And she said one day, I'm not even going to be able to have my last meal. So it seems to me, have your last meal all the time, because you have to know that the odds are very, very small that you'll be in the mood for a Nate 'n' Al's hot dog, which is my last meal.

That's in L.A.

Yes, and they FedEx.

You get them FedEx'd to you?

Oh yeah.

Why are they so great?

You know, I feel really bad that you've never had one. First of all, they have a really lovely skin on them. Not too thick, but just right.

And they're garlicky, but not too garlicky. They're spicy, a little teeny bit, but not too spicy. They're the perfect size. I mean, everything about them is sort of platonically fabulous, as hot dogs go.

I'm glad you brought up your friend's death, because there are two really memorable essays about her in this book and your last one. There are different deaths in our lives that have much greater impact for whatever reason, either they're really young and it's their first face of mortality ...

Yes, my grandfather.

Is that still very vivid to you?

No, I just had no idea what death was when my grandfather died. And I remember being told that grandpa was dead and thinking, oh, that's sad. And then about a month later I was sick and I thought Grandpa was going to come over and play casino with me. And then I realized he wasn't, ever. And that was kind of that first child's idea of, oh, that's what it means. He's not going to be there.

Was it accompanied by fear or just sadness?

No, just sadness. No, the thing with friends when you get older -- I mean this is not anything I haven't written about -- is they can't be replaced. When you're 30, you accumulate friends and you shed friends and you get closer at certain moments to some than others. And you have a huge bench of friends. And then that's just not true.

So the reason you've written about your friend's death ...

It's just that she was my very best friend. And that's that. There's never going to be another one. The person you can really talk to about anything. The person who knows your kids, whom your kids love, think of as family, all the things that happen over the years and that's gone. It's an amazing loss and almost everybody my age has that, that hole, where there used to be somebody.

You're at the age, too -- and you write about this -- when almost every week brings bad news. Do you become immune to it? Does it toughen you?

No, when it's someone you're really close to, not at all. No. But did you read the piece that Michael Kinsley did about illness and aging in the New Yorker? About how it's sort of the last piece of luck -- or bad luck. I'm paraphrasing, but I just remember reading it and thinking, oh yes, that is so true.

Luck in what kind of way?

Some people just get unbelievably lucky and they're like Kitty Hart and they live to be 94 years old and still performing at Carnegie Hall. And still with great legs. And then ...

But you've had good luck. The idea that you're 70 is shocking.

Thank you so much, thank you.

But does that help? You've been hearing that since the last book, too, people can't believe you're worried about age.

Well, I know, but you'll see someday that of course you think that, because you're young. We have very little imagination about almost anything. That's the truth.

I remember being young and looking at a table of older women having lunch. This was back in the day when older women had gray hair. And they were having this fantastically animated lunch. And I remember thinking something like, oh, look how much fun they're having. And they're so old! Now I realize they were probably younger than I am and, you know, it's one of the things that young people don't understand, that old people feel as if they're still young except in certain ways, which are all too horrible. Like the fact that you simply physically aren't what you used to be. But you really are the same person as you always were. And much wiser and yet, not. But younger people have no sense at all about older people. None. No imagination at all.

You mention "Heartburn" in this book a few times, and note that it was forged out of a grief and painful ...

No, no. Not a painful book to write. Going through [the divorce] was horrible. Writing about it wasn't horrible.

It was a product of going through this pain.

Yes. I knew, I knew I had a novel. I knew I had a something. If I could just find the voice to write and then one day I did. One day I just wrote the first eight or 10 pages of it, just like that. But I couldn't have done that while it was happening.

Do you think you're at your funniest when you're writing about something that's been painful?

Not necessarily, but I do think that if you can convert a certain kind of ... I'm already nervous about using the word "anger," because I'm not a particularly angry person, but I do think that underneath pieces like "I Feel Bad About My Neck" is some kind of actual anger about the aging process. Which then turns into a bunch of jokes. But I don't think all humor comes out of unhappiness or pain. There are simply too many funny people who had a completely, you know, normal childhood. Not necessarily happy, but who had a really happy childhood. Almost nobody worth knowing has a happy childhood.

I think there's always a portrait of you as very unflappable and impermeable. This is a very warm book. I'm wondering if that's something you've read about yourself from other people and you've taken notice of it.

Well, I think you know this: That very few people end up knowing who you are. I don't mean me. I just mean that most people are misunderstood in some way. I don't mean in a bad way. I just mean that they're not comprehended. But I don't really think about it a whole lot. And if I do think about it, I think I must do something to make them misunderstand me. But, what's for dinner?

Right. What can you do?

You write about your start in journalism, at Newsweek, in a "Mad Men" era when there was this incredible male hierarchy, and you were stuck in ...

... the girls' department.

The girls' department. I think it's an immensely confusing time for people who weren't there, because at the same time, you did have women like Lillian Ross, whom you write about in another essay, who was a big star at the New Yorker.

Well, there were exceptions to the rule. And I think there were always exceptions to the rule, fewer and fewer as you go back in time. But it was so clear in my house that we were all going to end up being writers. And that my extremely powerful, albeit eventually fairly wacky, parents would be disappointed in us if we weren't. And since our mother was a writer, you know, it all seemed like maybe this could be done, to me.

A friend of mine was a woman writer at Time -- Josie Davis, who died very young -- and you knew, therefore, that there weren't going to be any other [women] writers at Time. There was going to be one at a place. And the result of that was that there was a tremendous amount of submerged competition among the handful of us that were climbing the greasy pole. Because you really did think, is she going to get it? Or am I? There was never any sense that there was room for all of you. It seems to me that a great deal of that is gone now.

You then entered probably the hottest era in American magazines, writing for both Harold Hayes' Esquire and Clay Felker's New York. Were there more women there?

Clay had lots of women. Esquire didn't have many and, by the way, still doesn't.

But when I watch "Mad Men," it frustrates me so much, because it's 1964 and Don Draper is still wearing a hat? I don't think so! This is the stuff I get completely obsessed with.

In the book you talk about this, how it's a curse being older and knowing when the period details are wrong. Do they mistakenly have takeout pizza on "Mad Men"?

No, they don't. That was in "A Beautiful Mind." In 1948, takeout pizza in Princeton, N. J. I don't think so.

Does that just stop you cold?

It does. And then if you say that to anyone connected with the movies, they say, if you're thinking that you're not really in the movie. And I go, yeah, exactly. Exactly! That's what I'm trying to say to you.

I can't imagine you feel huge pangs of nostalgia seeing Newsweek teeter on the brink, but what do you think about the death, or pending demise, of some of these great publications?

I don't think I ever thought Newsweek was so important. Esquire is still with us. New York magazine is booming. New York is as good as it has ever been. I think I feel worse about places where I never worked.

But if you were graduating from college right now, where would you want to work?

I think I'd probably want to write for New York magazine.

Still.

Yeah, because print is still print. I found it fascinating that Tina Brown wanted to run a magazine, when she's done this great website. And we all know that Web is the future and print is the past, but you know, yeah sure. Even Rolling Stone I would be happy to write for. Even though I don't know anything about music.

But now you're a Web pioneer. Is it different? Is it exciting in different ways, writing for the Web?

Well, I just think for a handful of websites, you can't confuse what's on the Web with journalism. You know, [Salon has] actual journalism and there are a few other places that do. But mostly everybody else is just feeding off the carcass of the New York Times. So if I came to New York and wanted to be a journalist, I would want to work at a place where there's still journalism.

Were there any essays that were particularly tough to write?

Yes, yes, several of them. I would write them for a while, then just leave them unfinished.

The one about a famous story about a run-in between your mother and Lillian Ross that you were never quite sure was true or not.

The one about my mother and Lillian Ross was not so hard to write.

Really? I don't want to ruin it for anybody who will read it, but I thought it really tapped into a deep desire to justify hero worship in our parents. What made it easy to write, and why did you write about it now?

I think I was ready to write it. And believe me, if it were a triggering mechanism, I would not be able to tell you what it was, because I would have forgotten. But I don't remember having any struggle with it.

It's also just a great story.

Well, and it's always been a good story. And when it happened, when that part of it happened, when the pure Lillian Ross of it happened, it was such a coin dropping. It was such an amazing, oh my god, this is an extraordinary thing. But I've obviously known it for 30 years and never quite written that thing about my mother. Because it's really about my mother.

Although you've written a lot about your mother.

I have indeed, yes.

Is that one of your favorite stories about her?

Oh, I don't know. I think we all have a lot of stories about her. I was the luckiest of the sisters because I was the eldest. My mother used to always say, "You are not the eldest, you are the oldest." But I had more good years than any of them.

Because her condition deteriorated after you left.

She just didn't really become an alcoholic until I was 14 or 15 years old.

You include a painful scene about when she came to visit you at Wellesley when you graduated, and how you just hoped that she wouldn't embarrass you.

Yes, but my sister Delia's stories about her are so much darker and more horrible than mine. She got left with it. I want off to college and Delia was left with it.

The other Lillian essay in the book is about your one-time friendship with Lillian Hellman, and your regret over how it ended.

That was a very weird thing because in the course of writing it all came back to me how much fun she was. That memory had been so buried in all the stuff she had done later and in the end of it, you know the relationship kind of ended in its own way.

You recount all the excuses you had for shunning her, and really they're all ...

Perfectly good excuses.

Really good excuses.

I know, I know.

So is the sadness now at the way it ended a recent realization?

I had no idea I was going to end up there when I wrote it. I had no idea what it was. Sometimes you just say, I think I'll try writing about this and it doesn't work. There's a whole bunch of stuff that didn't work for this [book]. But that, I really didn't know where it was going. And it sat there for quite awhile. Then I started rereading her letters that were in a drawer, and I just felt everything. I felt the, oh this is so charming, oh this is so wonderful, oh I'm so lucky to get this, oh I'm so bored. There it all was. She was so divinely problematical until she was problematical. And I just hadn't come anywhere near all of that. And of course I wrote a play about her. So I had truly managed to push away any feelings I had toward her that might have made me feel guilty about having a certain amount of fun with her.

In a different essay, you talk about how getting old involves constantly thinking about reflecting on the great things, but also the little mistakes along the way that haunt you.

Or the big mistakes.

Or the big mistakes. Is that one of those little mistakes?

Well, I think I just feel that I could have been kinder. Big deal. You know? Especially when you're young, you're so puffed up with your standards. That's probably one of the only good things about being older is you have fewer and fewer standards.

Sure, and big deal, but at the same time, reading that essay in particular, it does make you think, gosh, will there be a lot of that? Will there be a lot of looking back and going ... oh.

Yes, there is. There is. That I can tell you.

Do you think it makes you a nicer person now?

No. Well, maybe it does. Maybe it does. You know. Somebody died this year, Daniel Schorr, whom I wrote about when he got fired by CBS [for Esquire in 1976]. And in retrospect, it's one of several things I've written in my life that I just think, oh get over yourself. Just really. How self-important could anyone have been. And he died and it just came marching back at me. Because you certainly write things when you are young, especially, that you just go, "Moving on... " It hurt someone's feelings and you just don't even think about it.

Last question. I imagine you love Thanksgiving. What's your go-to Thanksgiving dish?

You know, we've now aced the turkey.

Do you really like turkey?

I love turkey. I love it. In fact, I'm having turkey pangs right now, because it's time for turkey. But you don't ever have turkey from Oct. 1 to November something, because ...

It might ruin it.

It might ruin it. But we've discovered the way to cook a turkey, which I'm going to bore you with. Which is you take the turkey and you salt and pepper it, and you can put Lowry's seasoning salt on it if you want to, and you stick it in the pan at 450 and you do not do one thing to it. You don't baste it, you don't ...

Do you cover it?

You might have to cover it at certain point. And you might have to drain some of the fat that comes off, but it's all these years of endless basting for nothing, it turns out.

So your revelation is to do nothing.

Yes.

Shares