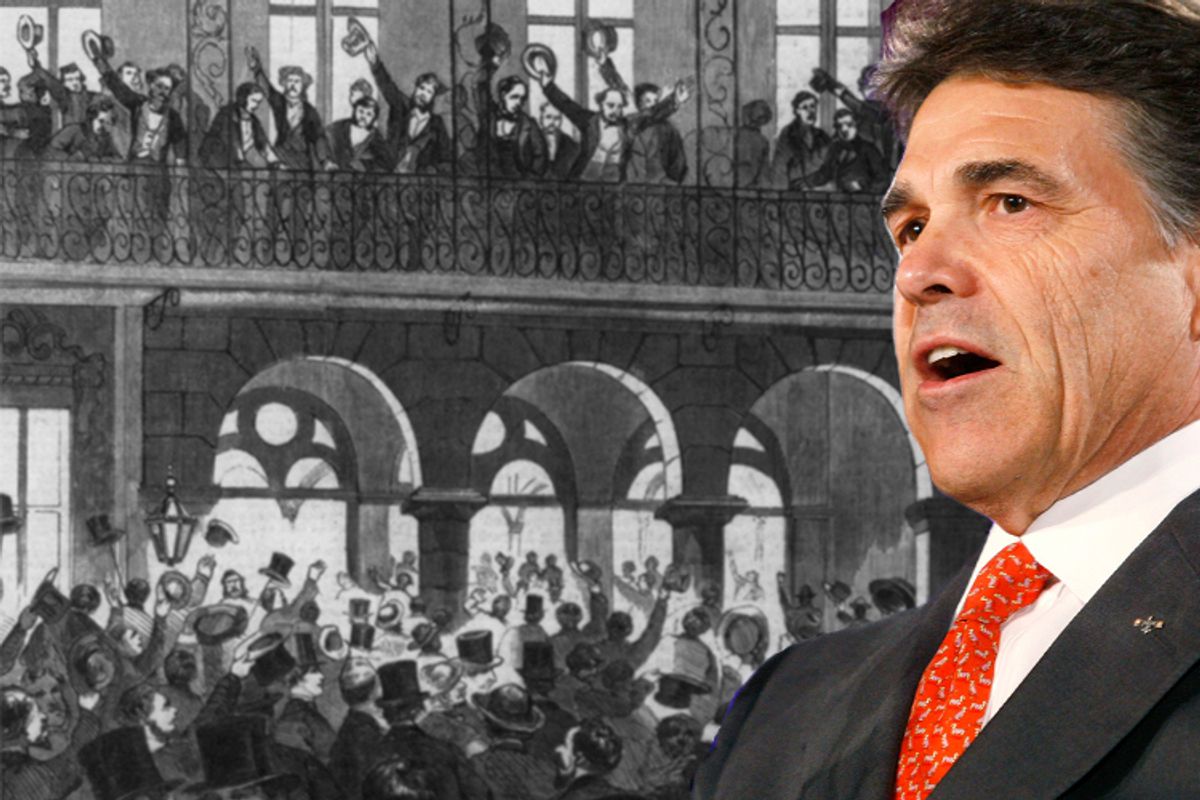

Secession is making a comeback. Tomorrow is the 150th anniversary of South Carolina’s secession from the Union, a political act that set in motion the events that led to the Civil War, but one needn’t look very far into the past to hear the rumblings of disunion and the rhetoric of states’ rights. In April 2009, Rick Perry, the Republican governor of Texas, suggested that his state might ponder secession if "Washington continues to thumb their nose at the American people." In response, the audience began to chant, "Secede, secede," hoping, one assumes, that everyone there would soon begin to party like it was 1860. The Texas House of Representatives quickly passed a resolution that seemed to threaten secession, and Gov. Perry just as quickly endorsed the resolution.

Yet if you think that all this secession bluster is only a symptom of some peculiar Texas Tea Party madness, you need only Google the word "secession" to find that the radical right believes, apparently in growing numbers, that the Constitution does not prohibit secession and that states can leave the federal union whenever they want. Worse, a Middlebury Institute/Zogby Poll taken in 2008 found that 22 percent of Americans believe that "any state or region has the right to peaceably secede and become an independent republic." That’s an astounding statistic, one that means that nearly a quarter of Americans don’t know about the Civil War and its outcome. Sadly, it also means that for 1 out of every 4 Americans, the 620,000 of their countrymen who died during the Civil War gave their lives in vain.

If by defeating the Confederacy during the Civil War, the Union did not prove conclusively that secession could not be legally sustained, the point was made emphatically clear in the 1869 U.S. Supreme Court decision, Texas v. White. In the majority opinion, written by Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase (a Republican appointed by Lincoln), the court ruled that under the Articles of Confederation, adopted by the states during the American Revolution, "the Union was solemnly declared to ‘be perpetual.’ And when these Articles were found to be inadequate to the exigencies of the country, the Constitution was ordained ‘to form a more perfect Union.’ It is difficult to convey the idea of indissoluble unity more clearly than by these words. What can be indissoluble if a perpetual Union, made more perfect, is not?" Chase, of course, was an activist judge, like his modern Republican successor John G. Roberts, but Lincoln had earlier made the same point about secession in his distinctively simple and disarmingly coherent style: "It is safe to assert that no government proper, ever had a provision in its organic law for its own termination." In his mind, secession was nothing short of anarchy. It was also treason. "No State, upon its own mere motion" he said in his first inaugural address, "can lawfully get out of the Union, -- that [secession] resolves and ordinances to that effect are legally void; and that acts of violence, within any State or States, against the authority of the United States, are insurrectionary or revolutionary."

Surprisingly enough, secessionist extremists (called fire-eaters in the parlance of the times) in the South agreed -- at least at first. In 1858, William Lowndes Yancey of Alabama proclaimed that the time had come to "fire the Southern heart -- instruct the Southern mind -- give courage to each other, and at the proper moment, by one organized, concerted action we can precipitate the cotton States into a revolution." After Lincoln’s election in November 1860, Sen. Judah Benjamin of Louisiana told a political ally that "a revolution of the most intense character" was moving forward and that it could not be "checked by human effort" any more than a prairie fire could be extinguished "by a gardener’s watering pot." When South Carolinians decided unanimously in their secession convention to leave the Union, the Charleston Mercury declared: "The tea has been thrown overboard. The revolution of 1860 has been initiated." One of the delegates admitted that the convention worked "to pull down our government and erect another." In Louisiana, a broadside declared: "We can never submit to Lincoln’s inauguration; the shades of Revolutionary sires will rise up to shame us if we shall do that." Many Southerners saw themselves as carrying the banner of their ancestors who had fought a revolutionary war against a tyrannical king; by rebelling against the United States, secessionists believed they were engaged in a revolution to restore the principles of 1776. When Texas left the Union on Feb. 1, 1861, the secessionists there proudly announced that "for less cause than this, our fathers separated from the Crown of England."

But talk of revolution was dangerous. Alexander Stephens, who would become the Confederacy’s only vice president, warned that "revolutions are much easier started than controlled, and the men who begin them, seldom end them." In many of the Southern states, Unionist sentiment remained strong, and several secession conventions were divided among those who wanted to leave the United States immediately, those who wished to wait for the Southern states to cooperate together by jointly seceding, and those who sought to prevent disunion entirely. Eventually the fire-eaters prevailed by whipping up passion -- that prairie fire mentioned by Benjamin -- and using fear tactics (e.g., Lincoln was an abolitionist bent on destroying the Southern way of life, meaning slavery) to convince moderates and conditional Unionists that secession was their only political option. By the time the Confederate government was formed in Montgomery, Ala., in February 1861, many Southerners -- like Jefferson Davis, the new Confederate president -- jettisoned the extremist rhetoric and espoused moderation, denying at the same time that secession constituted revolution. "Ours is not a revolution," Davis maintained. "We are not engaged in a quixotic fight for the rights of man; our struggle is for inherited rights." He claimed, in fact, that the Southern states had seceded "to save ourselves from a revolution."

His statement has led some historians to conclude that Southern secession was less a revolution than a counterrevolution -- a dubious interpretation that relies solely on taking Davis and some other Southerners at their word, when, in fact, what these Confederates were really attempting to do was justify secession by relying on the right of revolution articulated in the Declaration of Independence (or on the Lockean theory of "natural rights") rather than on anything found in the Constitution. In other words, Davis and his brethren did not want to be called traitors, even though they were leading a blatant political (and later an armed) rebellion against the existing government. To call secession a counterrevolution amounts to saying that Lincoln’s election to the presidency, which was accomplished legitimately under the law, was in itself a revolution. That proposition is, of course, preposterous.

More to the point, Confederate Vice President Stephens plainly asserted in March 1861 that the "present revolution," which had brought about the creation of the Confederate States of America, "is founded ... on the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery -- subordination to the superior race -- is his natural and normal condition. This, our new government, is the first in the history of the world based upon this great physical, philosophical, and moral truth." Other Confederates cringed at the persistent description of their revolution as a revolution (but not at the admission that the preservation of slavery was their primary motive for seceding) and turned instead to defending their actions by arguing that secession was, in fact, legal and not revolutionary at all. Harking back to the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions of 1798, written by James Madison and Thomas Jefferson in response to the Federalist Party’s enactment of the draconian Alien and Sedition Acts, Southerners advanced the idea that the Union under the Constitution consisted of simply a compact among the states and that any state, by means of its retained sovereignty, could divorce itself from the Union if it ever desired to do so. Confederates also based their rationalization of secession on John C. Calhoun’s notion of nullification, which held that a state could declare a federal law null and void. But Calhoun -- a South Carolinian who had served in Congress, as secretary of war under Monroe, as vice president under John Quincy Adams and Andrew Jackson, and later as the South’s most famous (or infamous) senator -- went further in his states’ rights arguments than Jefferson or Madison had ever done. In his view, states were not only sovereign, they were virtually independent; thus states were simultaneously in the Union and out of it. In 1832, President Andrew Jackson, a fellow Southerner, forced South Carolina to nullify its nullification of a federal tariff. Instead of reinforcing the idea of a perpetual Union, the nullification crisis simply laid the groundwork for the South’s later secession.

For many Southerners, the Union created under the Constitution was never meant to be a nation in perpetuity; they regarded it, instead, as a voluntary federation of autonomous states. To reach such a conclusion, of course, required tortured logic, since there was nothing in the Constitution that hinted at the possibility of a state seceding from the Union, just as there was nothing in the newly established Confederate Constitution that enabled any of its member states to secede. (The Confederate Constitution mimicked the U.S. Constitution in most of its particulars, except for legalizing slavery, limiting the president to a single term of six years, and giving the executive a line-item veto on budget matters.) What could be found in both constitutions, however, was a provision allowing for powers not delegated to the central government, "nor prohibited by it to the States," to be reserved to the states or to the people "respectively" (U.S. Constitution, Tenth Amendment; Confederate Constitution, Article VI, Section 6).

Not surprisingly, South Carolina in part based its secession on what it regarded as inherent rights granted by the Tenth Amendment. Modern secessionists like Rick Perry and other neo-Confederates (some of whom call themselves "Tenthers") also look to the Tenth Amendment to justify their disunionist -- and sometimes anarchic -- rants. The problem is, however, that if one is to be a consistent Jeffersonian in these matters, then a strict construction of the Tenth Amendment does not allow for any reading between the lines. Unfortunately for South Carolina in 1860 and Tenthers in 2010, the Constitution -- and especially the Tenth Amendment -- is silent on the issue of secession. The silence, despite all the hyperbole of secessionists old and new, does not mean that the Constitution condones the right of secession.

In any event, Southern secessionists believed that it did, so they came to see themselves as conservatives, not revolutionaries. This position entrapped them in the contradiction of wanting to overthrow the government of the United States while also remaining under the protection of the Constitution. As a result, Southern justifications of the constitutionality of secession and their own conservatism became almost surreal. The Reverend George Carter of Texas argued that secession, "so far from being a destructive process, was eminently conservative in its effects." Secession, in other words, did not tear the nation apart; rather, it provided the means by which true American virtues and principles could be conserved (while, of course, tearing the nation apart). In 1863, as the Civil War raged on, Carter told an enthusiastic crowd of like-minded disunionists: "Secession was conservative in the true sense. It preserved our rights and institutions by rejecting the control that sought to destroy them." As historian George C. Rable has insightfully noted, the Southern protests avowing conservatism and denouncing revolution eventually became Orwellian in their logic and rhetoric. "Submission is revolution; Secession will be conservatism," cried John M. Daniel, the editor of the Richmond Examiner. Just how twisted his logic had become was more fully revealed when he exclaimed: "To escape revolution in fact we must adopt revolution in form. To stand still is revolution -- revolution already inflicted on us by our bitter, fanatical, unrelenting enemies." Probably he knew what he meant, but what seems to have been at the core of his pronouncement was the hope that by simply saying a revolutionary act like secession was not really revolutionary would ensure that Confederates could not be branded as revolutionaries or traitors.

Even a conservative Confederate like Robert E. Lee, however, admitted that "secession is nothing but revolution." Despite this belief, he willingly broke his solemn oath to defend the Constitution, followed Virginia out of the Union, and became the Confederacy’s greatest warrior and its foremost national symbol. When the war was over, he sought a federal pardon. Implicitly he seemed to understand that his actions required absolution. But a war-torn nation was unforgiving. Lee’s rights as a citizen of the United States were not restored to him until 1975. Nevertheless, he was never charged with treason before his death in 1870, although he worried that he would be.

Jefferson Davis, however, was indicted for treason. Under the inept administration of Andrew Johnson, who bumbled his way through his presidency, federal prosecutors and Chief Justice Chase, a legal formalist, could not agree on anything beyond Davis’s indictment. Political fears and effective Northern Democrats, who had catered to Southern interests since the 1830s, led federal officials to satisfy themselves with keeping Davis incarcerated at Fortress Monroe in Virginia, where he spent a few days in shackles and later lived comfortably in a four-room apartment with his wife. After posting $100,000 in bail (raised in part from a secret Confederate fund kept in England), Davis was released; the federal government, continuing to stumble and to appease Southern demands, did not drop the case against him until early 1869. In 1978, the nation -- suffering from a bad case of historical amnesia as it often does -- restored Davis’ rights of citizenship.

One of America’s worst traitors, a man who had committed or condoned far worse acts against his country than Benedict Arnold, was allowed to go home after his brief detainment in Virginia. But even that lenient punishment was enough to elevate Davis to Southern martyrdom. Rumors were spread throughout the South about his mistreatment at Fortress Monroe, although Davis himself said the stories were untrue. Until his death in 1889, he found a stronger voice in passionately defending the right of secession and extolling the nobility of the Lost Cause. He became, like so many of his fellow Confederates, an unreconstructed rebel. As one might expect, he never believed that he had committed a single traitorous act; in fact, he boldly, even arrogantly, affirmed that every one of his actions was legal and constitutional. Unlike Lee, he never sought a pardon, which is just as well because he probably would not have gotten it (although President Johnson, who was courting the Democratic Party at the time, could have easily caved in on this issue). But he also never uttered a single word of regret or remorse for the bloody revolutionary war he had willfully led against his country.

It is, in fact, rather odd that Confederates should have denied so vehemently their revolutionary actions, especially when one considers their voluntary, even enthusiastic, taking up of arms against the United States, their desperate fight for independence from the United States, and their conscious modeling of their behavior on the Old Revolutionaries of 1776. The patriots of the American Revolution understood fully that their own rebellion began as a political protest against Great Britain’s imperial policies and involved what Americans like Jefferson and John Adams and Benjamin Franklin believed to be an effort to restore their rights as Englishmen -- what we might call a conservative political uprising. But in doing so, those patriots held firmly to an ideology of republicanism that was radical in all its implications: that the Creator had endowed all men with the inalienable rights of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. At the heart of this republican ideology was the extremely radical idea of equality. In the end, what began as a political controversy within the British empire resulted in the formulation of a new, original political science that, in turn, brought about the movement for independence and the establishment of an entirely new nation. The Founders fully understood that they were revolutionaries. They also famously grasped the reality that if their revolution failed, they would all be hanged. What had begun as a politically conservative protest climaxed in the radical act of founding a new country.

For decades after the Civil War, former Confederates emphatically denied that they were revolutionaries and traitors, although they continued to insist that their actions were equivalent to those taken by their forefathers, the Old Revolutionaries. Today’s Red State Republicans, Tea Party supporters, Tenthers and other right-wing extremists, particularly neo-Confederates, make the same arguments. Confederates then and now deny that they are traitors for championing nullification and secession. But that is precisely what they are.

How can anyone possibly be a patriot by calling for the destruction of the country one professes to love and honor? At the root of the theory of secession is an undemocratic impulse that calls for the splintering of the country into separate, sovereign entities. What the Tenthers seem to want here in the United States is the kind of implosion that led to the obliteration of Yugoslavia and the collapse of the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc countries in recent times. If the Founders had wanted to create a federation of independent nations, such as the modern European Union, they would have done so. If they had wanted to create a union of autonomous countries aligned under a single head of state, such as the United Kingdom’s Commonwealth of Nations, they would have done so. But they did not. Instead, they brought forth a new republic, a new nation, in which sovereignty was not placed in the hands of the executive authority (such as a monarch or a president), or in the hands of a legislature (such as Parliament or Congress), or in the hands of the separate states (as the Confederacy tried to do and failed), but in the hands of the people -- which is precisely why the Constitution begins with the words, "We the People." Recent threats of secession, like the ones made so forcefully by Gov. Perry, are dangerous because they are, in essence, anti-American. They threaten to tear apart the country, just as the Southern slave states did by seceding and then by engaging in an armed rebellion against the United States.

But even peaceful disunionist sentiments -- like the ones Confederate secessionists had when they believed that the federal government would let them abandon the nation without any resistance -- are also potentially treasonous. You either give your full allegiance to the United States or you don’t. You may not like the president, the Congress, your local dog catcher, but even if your own personal political preferences aren’t currently in effect, you can’t simply say "hasta la vista, baby," and set up your own separate Republic of Me. I say this without invoking the old bumper-sticker platitudes of "My Country, Right or Wrong" or "America -- Love It or Leave It." I am simply pointing out that the Civil War ended the debate over whether a state can leave the Union. The answer is no, it can’t, but if you think it can, then you are falling far short of your duty and responsibility as a citizen of the United States.

Rhetoric is one thing, action another. The political blather of extremists on the right or left is something the nation can endure -- it always has, it always will. Southerners threatened secession for decades leading up to the Civil War and succeeded mostly in convincing Northerners that their talk was nothing more than a bluff. When Confederates finally took up arms, proving their words were no bluff, the North started shooting back at them. It should be obvious, then, that any serious suggestion of secession in our own time is perilous. And, quite frankly, when it comes to secession (and not just the more benign "opting out" of federal programs, which in some cases are voluntary anyway), words put into action would become treason. Nor does the right of revolution -- enshrined in the words of the Declaration of Independence -- allow you to foment rebellion without paying the consequences. You have every right to rise up in revolution. But when you do so, you become an enemy of the United States. There is no gray area, no wiggle room, that allows you to claim that because the Constitution does not mention secession, it therefore must be legal, and, oh, by the way, beginning on Tuesday Texas will henceforth be an independent republic. If Texas desires to leave the Union, then the president and Congress are duty-bound to prevent it from doing so. The aphorism "Don’t Mess with Texas" has no relevancy. Neither Texas nor any other state can secede from the Union without paying the consequences (or, for that matter, paying back to Washington all the federal dollars it has received since 1845, when it very willingly entered the Union). That’s what the lesson of the Civil War is, although Tenthers and other potential disunionists seem not to have learned it.

Where I come from (New England), there are many people who would be very willing to let Texas leave the Union while wishing it a hearty bon voyage (not me, necessarily -- my paternal grandparents lived for a long time in San Antonio and loved the place; I’m rather fond of the Alamo and the Riverwalk, and Austin’s OK, too). It might even be conceivable that the rising tide of secession sentiment in this country could eventually lead to a state deciding to leave the Union for good; it might also be conceivable for such an event to take place while a weak-willed president occupied the White House -- someone more like, say, James Buchanan than Abraham Lincoln. If so, that act of secession would be the beginning of the end of the United States. For once the theory of secession is put into practice, there would be no stopping the fragmentation. The nation -- and all that it stands for, all that it has meant -- would be finished forever. As the sociologist Immanuel Wallerstein points out, "Once the logic of secession is admitted, there is no end except in anarchy." In pledging allegiance to the flag, Americans vow to uphold "one nation, indivisible." For Lincoln, the issue was straightforward. Secession was revolution. Secession was treason. There still should be no doubt about that, especially as we ponder the meaning of the 150th anniversary of South Carolina’s ignominious -- and traitorous -- secession from the Union.

Shares