(updated below)

One of the more eye-opening events for me of 2010 occurred in March, when I first wrote about WikiLeaks and the war the Pentagon was waging on it (as evidenced by its classified 2008 report branding the website an enemy and planning how to destroy it). At the time, few had heard of the group -- it was before it had released the video of the Apache helicopter attack -- but I nonetheless believed it could perform vitally important functions and thus encouraged readers to donate to it and otherwise support it. In response, there were numerous people -- via email, comments, and other means -- who expressed a serious fear of doing so: they were worried that donating money to a group so disliked by the government would cause them to be placed on various lists or, worse, incur criminal liability for materially supporting a Terrorist organization.

At the time, I dismissed those concerns as both ill-founded and even slightly paranoid. From a strictly legal standpoint, those concerns were and are ill-founded: WikiLeaks has never even been charged with, let alone convicted of, any crime, nor does it do anything different than what major newspapers around the world routinely do, nor has it been formally designated a Terrorist organization, nor -- I believed at the time -- could it ever be so designated. There is not -- and cannot remotely be -- anything illegal about donating to it. Any efforts to retroactively criminalize such donations would be a classic case of an "ex post facto" law unquestionably barred by the Constitution. But from a political perspective, the crux of the fear was probably more prescient than paranoid: within a matter of months, leading right-wing figures were equating WikiLeaks to Al Qaeda, while the Vice President of the U.S. went on Meet the Press and disgustingly called Julian Assange a "terrorist."

But more significant than the legal soundness of this fear was what the fear itself signified. Most of those expressing these concerns were perfectly rational, smart, well-informed American citizens. And yet they were petrified that merely donating money to a non-violent political and journalistic group whose goals they supported would subject them to invasive government scrutiny or, worse, turn them into criminals. A government can guarantee all the political liberties in the world on paper (free speech, free assembly, freedom of association), but if it succeeds in frightening the citizenry out of exercising those rights, they become meaningless.

So much of what the U.S. Government has done over the last decade has been devoted to creating and strengthening this climate of fear. Attacking Iraq under the terrorizing banner of "shock and awe"; disappearing people to secret prisons; abducting them and shipping them to what Newsweek's Jonathan Alter (when advocating this) euphemistically called "our less squeamish allies"; throwing them in cages for years without charges, dressed in orange jumpsuits and shackles; creating a worldwide torture regime; spying on Americans without warrants and asserting the power to arrest them on U.S. soil without charges: all of this had one overarching objective. It was designed to create a climate of repression and intimidation by signaling to the world -- and its own citizens -- that the U.S. was unconstrained by law, by conventions, by morality, or by anything else: the government would do whatever it wanted to anyone it wanted, and those thinking about opposing the U.S. in any way, through means legitimate or illegitimate, should (and would) thus think twice, at least.

That a large percentage of those brutalized by this system turned out to be innocent -- knowingly innocent -- is a feature, not a bug: that one can end up being subjected to these lawless horrors despite doing nothing wrong only intensifies the fear and makes it more effective. The power being asserted is not merely unlimited and tyrannical, but arbitrary. And now, the Obama administration's citizen-aimed, due-process-free assassination program, its orgies of drone attacks, its defense of radically broad interpretations of "material support" criminal statutes, and its disturbing targeting of American anti-war activists with subpoenas and armed police raids are all part of the same tactic. Those contemplating meaningful opposition to American action are meant to be frightened. The anguished, helpless cries of 18-year-old American Gulet Mohamed, after a week of being disappeared and brutalized by America's close ally, serves an important purpose.

* * * * *

Consider how this expresses itself with regard to WikiLeaks. Jacob Appelbaum was first identified as a WikiLeaks volunteer in the middle of 2010. Almost immediately thereafter, he was subjected to serious harassment and intimidation when, while re-entering the U.S. from a foreign trip, he was detained and interrogated for hours by Homeland Security agents, and had his laptop and cellphones seized -- all without a warrant. He was told he'd be subjected to the same treatment every time he tried to re-enter the country (and his belongings, months later, have still not been returned). And he was one of the individuals singled out in the DOJ's court-issued subpoena to Twitter.

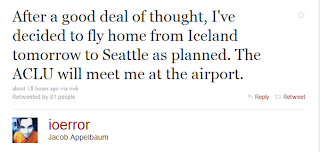

Since that airport incident, Appelbaum has been extremely (and understandably) cautious about speaking out publicly on anything having to do with WikiLeaks. In other words, he passionately believes in the cause of transparency promoted by WikiLeaks, but is afraid to exercise his free speech rights to advocate for that cause. Two weeks ago, he left the U.S. for the first time since that incident and has talked about the trepidation he feels when returning. Last night, he posted this on Twitter:

That's an American citizen who has never been charged with any crime: afraid to return to his own country, and then deciding to do so only with ACLU lawyers meeting him at the airport.

That's an American citizen who has never been charged with any crime: afraid to return to his own country, and then deciding to do so only with ACLU lawyers meeting him at the airport.

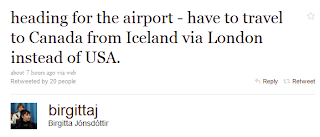

Or consider Birgitta Jónsdóttir, the former WikiLeaks volunteer and current elected member of Iceland's Parliament whose Twitter account was also the target of the DOJ's snooping (prompting Iceland's government this morning to summon the U.S. Ambassador for an explanation). She was scheduled to leave on a long-planned trip to Canada for a conference and last night wrote this about her travel plans:

That's an elected member of the Parliament of a NATO country who -- after having the DOJ use the federal courts to snoop through her private online information -- is now afraid to fly through the U.S.

And these fears are well-justified. Anyone connected to WikiLeaks -- even American citizens -- are now routinely detained at the airport and have their property seized, their laptops and cellphones taken and searched and retained without a shred of judicial oversight or due process. And this treatment extends to numerous critics of the government having nothing to do with WikiLeaks. In the past month, I've spoken with American writers, photographers and filmmakers -- who are not ready yet to go public -- who have experienced similar and even worse harassment when entering the U.S. Notably, like anyone remotely connected to WikiLeaks, all of them -- given the government's broad surveillance powers -- insist upon communicating only behind multiple, highly fortified walls of encryption. The U.S. Government plainly wants any genuine critics to feel fear, and is willing to use any means -- no matter how lawless and extreme -- to induce it.

Yesterday, computer security expert Chris Soghoian documented how little the DOJ can hope to learn from the court-ordered Subpoena issued to Twitter (given how limited is the information stored on Twitter). But that's the point: the goal of that Order isn't to learn anything; it's to signal to anyone who would support WikiLeaks that they will be subject to the most invasive surveillance imaginable. I met two months ago with a former WikiLeaks volunteer who believes as fervently as ever in its cause, but ceased working with them because his country has a broad extradition treaty with the U.S. and he was petrified that his government, upon a mere request by the U.S., would turn him over to the Americans and he'd disappear into the world of the Patriot Act and "enemy combatants" and due-process-free indefinite detention still vigorously applied to foreigners.

This is the same reason for keeping Bradley Manning in such inhumane, brutal conditions despite there being no security justification for it: they want to intimidate any future whistleblowers who discover secret American criminality and corruption from exposing it (you'll end up erased like Bradley Manning). And that's also what motivates the other extra-legal actions taken by the Obama administration aimed at WikiLeaks -- from publicly labeling Assange a Terrorist to bullying private companies to cut off ties to chest-beating vows to prosecute them: they know there's nothing illegal about reporting on classified American actions, so they want to thuggishly intimidate anyone from exercising those rights through this climate of repression.

Beyond the erosion of freedom, there's a serious cost to all of this. Virtually the entire world uses Twitter now, and the efforts by the U.S. Government to invade people's accounts -- including an elected member of Iceland's Parliament -- made headlines around the world. Many Americans may not perceive it, but much of the world, as a result of such actions, sees the U.S. not as "Leaders of the Free World" but one of the greatest threats to privacy and other core liberties. Watching people afraid to fly through the U.S. -- including its own citizens -- is just remarkable. And the spectacle of Homeland Security agents detaining whomever they want, and then unilaterally stealing their laptops and cellphones and keeping them and digging through them for as long as they want -- all without a warrant -- is a powerful sign of how far things have fallen.

Beyond the erosion of freedom, there's a serious cost to all of this. Virtually the entire world uses Twitter now, and the efforts by the U.S. Government to invade people's accounts -- including an elected member of Iceland's Parliament -- made headlines around the world. Many Americans may not perceive it, but much of the world, as a result of such actions, sees the U.S. not as "Leaders of the Free World" but one of the greatest threats to privacy and other core liberties. Watching people afraid to fly through the U.S. -- including its own citizens -- is just remarkable. And the spectacle of Homeland Security agents detaining whomever they want, and then unilaterally stealing their laptops and cellphones and keeping them and digging through them for as long as they want -- all without a warrant -- is a powerful sign of how far things have fallen.

* * * * *

As always, many people would respond to claims of this sort by believing they're hyperbolic. The reason for that is obvious: none of this happens to them. And the reason it doesn't is because they're not engaged in any actual dissent; they're not opposing the U.S. Government in any meaningful way. They're Good Citizens, supportive of their government (or critical only in the most tepid and deferential ways), and thus not targeted by such measures. So they don't perceive them, or if they do, don't believe they're a problem. But that's how repression always works: it's targeted only at the faction that is actually adversarial to political or other elite power.

People who spout pieties are never targeted with censorship, since there's nothing to censor. Only those whose views are threatening or marginalized are subjected to such measures. Identically, media outlets that engage in government-subservient reporting are not the target of the government's wrath; only those whose reporting undermines government interests (such as WikiLeaks) are so targeted. And most people are not being detained at the airport and having their laptops searched, seized and copied -- or having their Twitter and other communications invaded -- because they're not doing anything to bother the government; it's those who are who experience that intimidation. But political liberties are meaningless if they're conditioned on obeisance to political power or if citizens are frightened out of exercising them in any way that matters.

There has been much talk over the last several days, in the wake of the Arizona shooting, about attempts by some citizens to instill physical fear in elected officials. That's a worthwhile and necessary topic, but the fear that government officials are attempting to instill in law-abiding, dissenting citizens is far more substantial and sustained, and deserves much more attention than it has received.

UPDATE: 4 related items: (1) The Los Angeles Times has a surprisingly strong editorial today condemning what it calls the "indefensible" conditions of Bradley Manning's detention; (2) McClatchy's Nancy Youssef has a very good article examining why American journalists -- in contrast to journalists from around the world -- refuse to defend WikiLeaks from government attacks; (3) Forbes notes that in the wake of speculation that the DOJ's pursuit of Twitter data may include the names of those who follow WikiLeaks on Twitter (I personally don't think it does include that), WikiLeaks quickly lost 3,000 followers on Twitter, presumably people now too afraid to continue to follow them; and (4) The Miami Herald's Carol Rosenberg notes the latest glorious milestone of our National Security State: "Guantanamo prison camps enter their 10th year tomorrow."

Shares