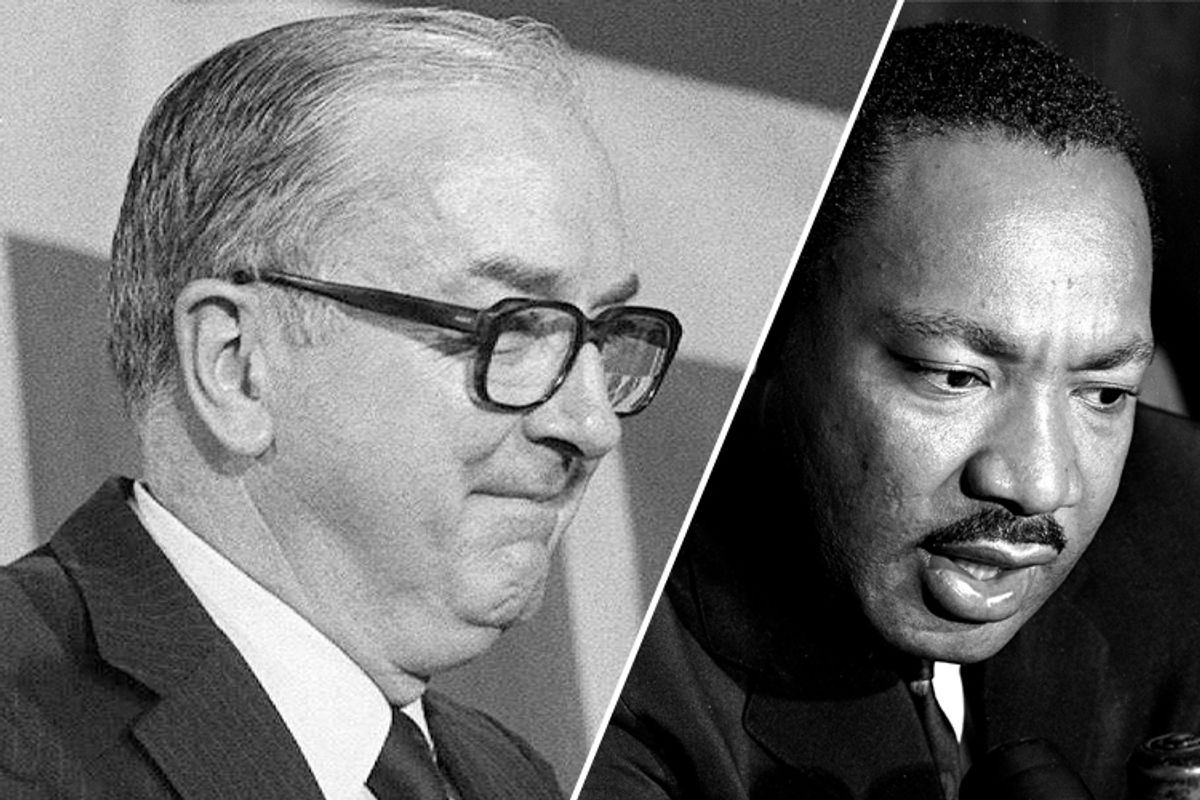

The national holiday commemorating Martin Luther King that we celebrate today comes with a bitter irony: Its creation nearly three decades ago was instrumental in rescuing and extending the career of one of the most notorious race-baiters in modern American politics.

It was the fall of 1983 and Jesse Helms seemed destined for political extinction. The staunchly conservative senator was due to stand for reelection the following year, and polls in North Carolina showed him running far, far behind the Democrat who was gearing up to oppose him, Jim Hunt.

That Helms was even in the Senate was something of a fluke; the coattails of Richard Nixon, who carried North Carolina by 40 points over George McGovern in 1972, had been the main reason for his eight-point victory in his first campaign. And even in the early '80s, North Carolina was still filled with culturally conservative white voters who had been trained from birth to support Democrats. One survey showed Hunt, a moderate who was finishing his second term as governor, 22 points ahead of Helms. Another put the margin at 19. Incumbent senators just aren't supposed to overcome those kinds of deficits.

But those polls were taken before the first week of October '83, when the bill to create a federal holiday honoring King -- which had easily cleared the House over the summer -- landed in the Senate. Two of the chamber's top Republicans, Howard Baker and Bob Dole, embraced it and urged their colleagues to do the same. The GOP had once been the party of civil rights, and they hoped to attract black voters back into the fold -- both for the '84 Senate elections and for the long-term future of their party.

Helms, though, saw a much different opportunity: to give those conservative white voters in his state a reason to buck their partisan heritage and side with their Republican senator in '84. Thus it was that he declared his intent to filibuster the King holiday, claiming the slain civil rights hero had been a devotee of "action-oriented Marxism" and that the movement he'd led had actually been a haven for Communists.

It didn't matter that he stood little chance of prevailing in the legislative fight. By the fall of 1983, even Ronald Reagan, like Helms a hero of the New Right (whose political career was probably saved by Helms' assistance in North Carolina's 1976 presidential primary), had come around to supporting the idea of a King holiday -- or at least to saying that he'd sign the bill if it reached his desk. Previously, Reagan had offered the standard line of King holiday opponents that giving federal workers a new day off would be too expensive. As J. Bennett Johnston, a Democratic senator from Louisiana, explained to the New York Times, "If you took a secret poll, the Senate would not want additional holidays. But the symbolism of it is so strong, that sweeps aside those arguments very quickly.''

But Helms wasn't interested in the outcome; he was interested in the show. Undoubtedly, then, he was tickled when one of the first Democrats to lash out at his filibuster was Ted Kennedy -- precisely the kind of unabashedly liberal, integrationist Northern liberal who reminded those white Southern Democrats why they'd been abandoning their party in recent presidential elections. "Everybody who disagrees with Mr. Kennedy is a racist and right-winger," Helms sneered. With a massive push underway to register black North Carolinians to vote, Helms was asked if his stand might hurt him in 1984. But he knew better: "I'm not getting any black votes, period."

Within days, Helms struck a deal with Baker, then the chamber's majority leader, to give up his filibuster. In exchange, the final vote would be put off for two weeks, which would give Helms time to pursue a legal bid to force the Justice Department to release the files that J. Edgar Hoover's FBI had compiled on King. This, too, was a doomed mission, not that Helms cared. What it really meant was two more weeks at the center of a national media firestorm, making one more stand for old Dixie against Kennedy and the rest of the liberals.

The Senate debate kicked off on Oct. 18, a Tuesday, with Helms -- his legal effort squelched by a federal judge the day before -- offering a motion to send the bill back to the Judiciary Committee so that King's ties to "elements of the Communist Party USA" could be fully explored. What he was really trying to do, though, was bait Kennedy into a face-to-face showdown. The Massachusetts Democrat, fully aware of what Helms was looking for, had already indicated that he wouldn't respond personally to any of Helms' claims. But his thinking changed when Helms brought up Kennedy's two slain brothers, John and Robert, who had approved a temporary wiretap of King in the fall of 1963.

"His argument is not with the senator from North Carolina," Helms said of Kennedy. "His argument is with his own dead brother who was president and with his dead brother who was the attorney general."

That brought Kennedy to the floor to declare that "I am appalled at the attempt of some to misappropriate the memory of my brother Robert Kennedy and misuse it as part of this smear campaign. Those who never cared for him in life now invoke his name when he can no longer speak for himself.'' Kennedy also accused Helms of making a "false" statement -- that the King bill never received committee hearings. Helms immediately objected to Kennedy's language, claiming that it was a violation of rules that prohibit senators from questioning each other's honor. Baker convinced Kennedy to substitute the word "inaccurate," though Kennedy did manage another swipe: "The senator," he said of Helms, "needs to learn the rules."

On and on it went, with one outraged liberal after another rising to defend King's name and to take exception to Helms' words. In a particularly memorable scene, New York's Daniel Patrick Moynihan held up a binder of documents about King that Helms was promoting, pronounced it a "packet of filth," and dropped it on the ground. Even Dole, who served as the bill's floor manager, took on Helms, saying of his claim that the holiday would waste money, "Since when did a dollar sign take its place atop our moral code?"

Eventually, Helms' motion was rejected, 76-12. So were a series of other motions designed to derail or alter the proposed holiday. The next day, the vote on the main bill was finally called, and it passed with ease, 78 to 22. "It's a tyranny of the minority!" Helms roared.

Very quickly, it became clear that Helms' grandstanding hadn't been in vain. By the time the King fight was over, polls showed Hunt's lead vanishing -- down to single digits, less than half of what it had been months earlier. As the campaign unfolded, racial resentment became Helms' prime weapon. Helms fliers and mailers featured large photos of Hunt and Jesse Jackson and cast the black voter registration drive as a sinister effort to disenfranchise whites. Helms himself told audiences that Hunt was a racist because he was relying on black voters, and in the closing stretch, he reminded voters that Hunt needed "the bloc vote" to win. Asked what he meant by that, Helms didn't mince words: "the black vote."

On Election Day 1984, Helms did what had looked impossible just over a year earlier: He beat Hunt. Divide and conquer had worked brilliantly. Whites went for Helms by a 63-37 percent ratio (the spreads were much bigger in rural areas). Blacks went for Hunt 99 to 1 percent. Overall, the ratio was 52 to 48 percent for the incumbent. On that same day, Reagan was reelected in a resounding landslide, while Republicans held on to their Senate majority. When it came to 1984, the King fight, clearly, hadn't hurt the GOP.

And yet it was a momentous occasion in the rise of the modern Republican Party. For a century after the Civil War, the GOP had been the progressive party when it came to race and civil rights. But it all changed, virtually overnight, when the burgeoning conservative movement succeeded in nominating Barry Goldwater -- who had joined the Southern filibuster of the Civil Rights Act that Lyndon Johnson signed in 1964 -- to run against LBJ. This was the moment that white Southern conservatives like Helms, who had been Democrats their whole lives, began a steady, decades-long migration to the GOP. The King vote in '83 demonstrated how far along that process was. Of the 22 "no" votes, 18 came from Republicans. Just two decades earlier, all but six of the 29 votes to filibuster Civil Rights had come from Democrats.

When the King holiday cleared the Senate, Dole called a press conference and heralded the fact that 37 Republicans had voted for it. It reflected, he claimed, his party's inclusive spirit. But the scandal was that 18 of them hadn't. And the message that most African Americans seemed to take from this was simple: The party that makes a home for Jesse Helms doesn't deserve to be my home.

Shares