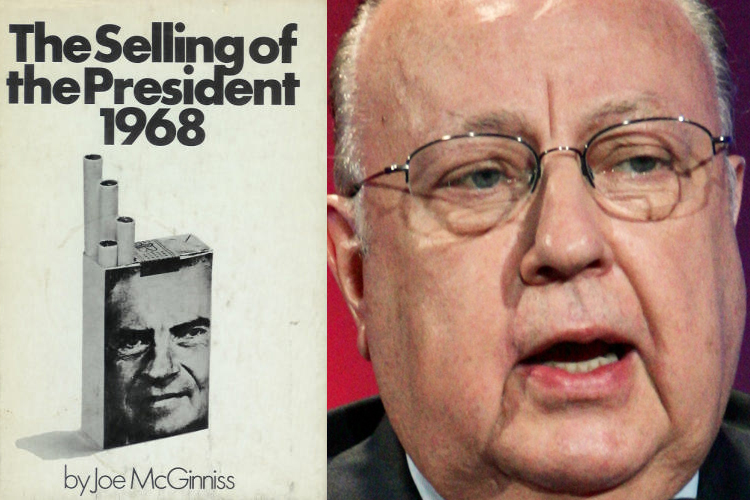

The Internet is buzzing about Tom Junod’s Esquire profile of Roger Ailes, and with good reason: It offers some great details and terrific writing. It also offers an excuse to look back at Joe McGinniss’ “The Selling of the President” (1969), the classic of campaign reporting that first introduced many readers to the stage-managed world of political theater — and to a 27-year-old Roger Ailes, the man who decades later would create the Fox News Channel.

McGinniss based his book on the unlimited access granted to him by Richard Nixon’s media team during the 1968 presidential campaign. “Voters are basically lazy,” read one memo obtained by McGinniss. “Reason requires a high degree of discipline, of concentration; impression is easier. Reason pushes the viewer back … Impression can envelop him, invite him in.” Ailes deftly applied these principles to a series of televised town halls that proved crucial to Nixon’s victory. Even today, McGinniss’ book can tell us something about Ailes. Considered in the context of Junod’s new profile, though, it can also tell us something about the evolution of political journalism.

While Harry Treleaven and Frank Shakespeare took care of Nixon’s television ads, Ailes handled the town halls, which ran in 10 different markets. Ailes settled on a format where Nixon appeared before a friendly studio audience and answered questions from a pre-selected panel of six or seven people. “Let’s face it,” Ailes told McGinniss — and his book’s strengths come from its frank dialogue and McGinniss’ deadpan tone — “a lot of people think Nixon is dull. Think he’s a bore, a pain in the ass. They look at him as the kind of kid who always carried a bookbag … Now you put him on television, you’ve got a problem right away. He’s a funny-looking guy. He looks like somebody hung him in a closet overnight and he jumps out in the morning with his suit all bunched up and starts running around saying, ‘I want to be President.’ I mean this is how he strikes some people. That’s why these shows are important. To make them forget all that.”

Ailes loved explaining how he helped his audience forget. And in McGinniss’ book, as in Junod’s profile, he comes across as competitive, vindictive — and very, very good. With his town halls, Ailes controlled the smallest details. (After the first broadcast, he wrote an exhaustive, itemized memo: “F-2: I may try slightly whiter makeup on [Nixon’s] upper eyelids.”) He obsessed over the presentation. (“I’m going to fire this fucking director. I’m going to fire the son of a bitch right after the show,” Ailes said during another broadcast that lacked sufficient close-ups. “I want to see faces. I want to see pores. That’s what people are. That’s what television is.”) He refined Nixon’s delivery. (Ailes pushed Nixon to cut a 2 minute 35 second answer on the economy to 1 minute 10 seconds. “I don’t want to take a chance of missing the shots of the audience crowding around him at the end,” he explained.)

But Ailes remained most concerned with his panels, which he balanced according to age, ethnicity and occupation. While prepping a Philadelphia broadcast, Ailes admitted that “on this one we definitely need a Negro … U. S. News and World Report this week says that one of every three votes cast in Philadelphia will be Negro. And goddammit, we’re locked into the thing, anyway. Once you start it’s hard as hell to stop, because the press will pick it up and make a big deal out of why no Negro all of a sudden.”

McGinniss seemed particularly struck by Nixon’s region-specific rhetoric. For example, the campaign designed specific ads to run during wrestling and “country and western programs.” But Nixon also customized his message for Ailes’ broadcasts — “nothing big enough to make headlines,” McGinniss writes, “just a subtle twist of inflection, or the presence or absence of a frown.”

This won’t surprise anyone who’s witnessed Fox News’ narrow-casting. But in 1969, it was a revelation. Already, McGinniss could (and did) quote Daniel Boorstin and Marshall McLuhan on the superficial, celebrity-driven nature of television. But he backed up their theories with concrete examples and translated them to the political arena. Theodore White, who, by this point, had actually copyrighted the phrase “The Making of the President,” didn’t even mention Ailes in his book on the ’68 election. McGinniss used Ailes to show how modern campaigning worked.

McGinniss, a 26-year-old sports columnist, stumbled across his book’s topic while taking a train to New York. A fellow commuter had just landed the Hubert Humphrey account and was boasting that “in six weeks we’ll have him looking better than Abraham Lincoln.” McGinniss tried to get access to Humphrey’s campaign first, but they turned him down. So he called up Nixon’s, and they said yes.

“The Selling of the President” spent more than six months on best-sellers lists, and McGinniss sold a lot of those books through television, appearing on the titular shows of Merv Griffin, David Frost and Dick Cavett, among others. On “Today,” Barbara Walters tore into McGinniss on air — because, he later learned, she was friends with Ailes (she referred to him as “Roger”) and worried the book would end his career. In fact, Ailes loved the book. He even did a radio show with McGinniss to promote it, and Ailes was surely as proud and funny and profane as he is in the pages of “The Selling of the President.”

But that was then, and this is now. For his Esquire profile, Junod did a ton of reporting — enough to sustain not only the story, but also an ongoing series of interviews and outtakes. But he never got Ailes to open up in the way McGinniss did. The best contrast comes in their handling of Ailes’ blue-collar background. Ailes keeps pitching himself to Junod as an ex-ditch digger, “an average guy from flyover country.” In “The Selling of the President,” though, Ailes doesn’t seem to care. It’s not just that he runs around skydiving for pleasure and ranting at hotel staffers (and, for that matter, firing the close-up-challenged director); it’s that he sees the residents of flyover country as nothing more than a political variable. At one point, Nixon’s staff suggests that Ailes include a farmer on one of his television panels. “No! No more farmers,” he replies. “They all ask the same goddamn dull questions.”

It’d be easy to chalk this shift up to Ailes’ increased media savvy. After all, “Barbara” aside, Ailes fed Junod the same line about avoiding Manhattan media parties that he did the New York Times a year ago. But the change in Ailes is also a change in the reporter’s focus. Even in 1968, people were surprised by the candor of Ailes et al. (William Buckley assumed McGinniss had relied on “an elaborate deception which has brought joy and hope to the Nixon-haters.” But even Buckley liked the book.) More important, Junod seems less interested in Ailes’ methods than in his motivations. The Esquire profile doesn’t contain anything like the recently leaked Fox News memos because that was never its point.

A comparison of Ailes in 1968 and 2011, then, suggests that journalism itself has become more personality-driven. This doesn’t mean it’s worse, as some of Junod’s best moments center on trying to understand Ailes. But it does suggest we’re now less interested in how the sausage is made or sold than in why someone got into the sausage business in the first place. This is true of McGinniss, too. His 2011 self is writing a book on Sarah Palin, and access has been hard to come by.