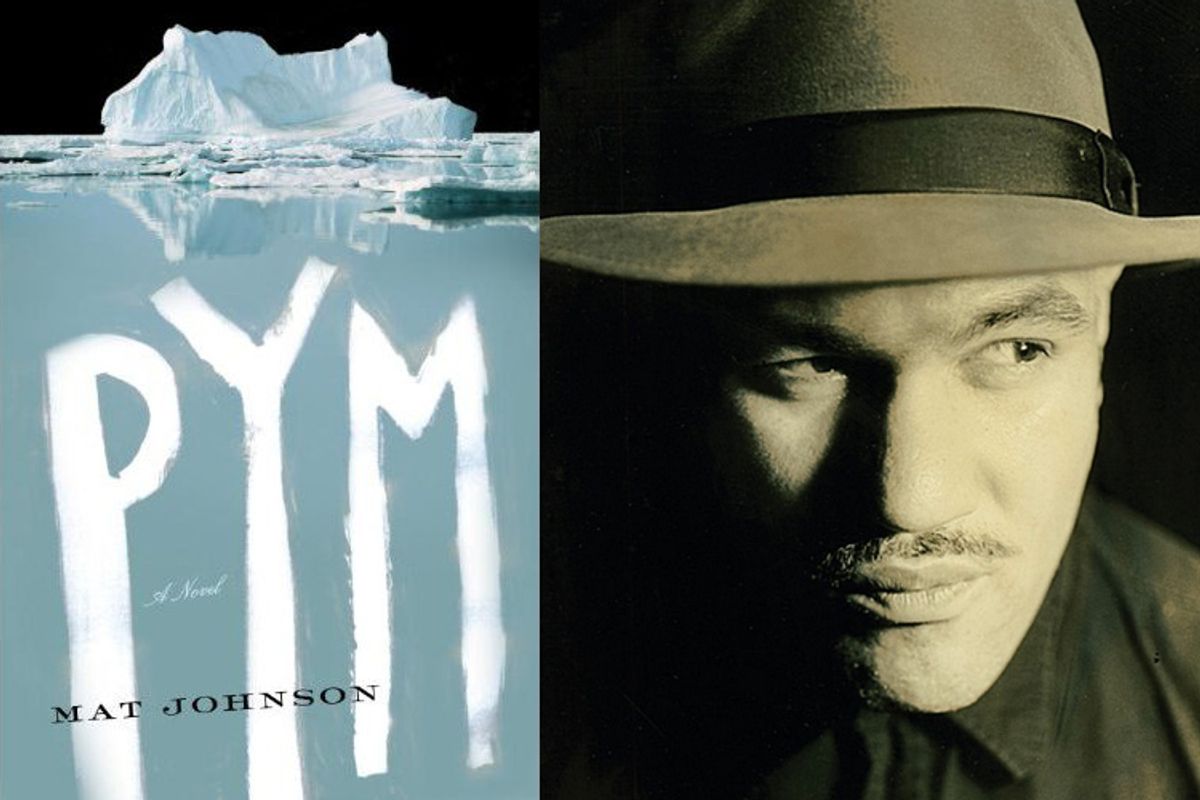

"Pym," by Mat Johnson is a blisteringly funny satire of contemporary American racial attitudes -- which is quite an accomplishment when you consider that most of the novel is set in the wilds of Antarctica. It's the story of Christopher Jaynes, a "blackademic" at a small liberal arts college in the Hudson River Valley who fails to make tenure, in part because of his refusal to sit on the Diversity Committee. "The Diversity Committee," he explains to his successor (a "Hip-Hop Theorist"), "has one primary purpose: so that the school can say it has a diversity committee. ... People find that very relaxing. It's sort of like, if you had a fire, and instead of putting it out, you formed a fire committee."

But the real reason why Jaynes loses his job may be his obsession with "The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket," the only novel written by Edgar Allan Poe and surely one of the weirdest texts in the American canon. It describes the eponymous Pym's adventures sailing the South Seas and ends, prematurely, with an enigmatic vision of a towering figure, shrouded in white, looming over a foaming cataract in Antarctica. " 'Pym' that is maddening, 'Pym' that is brilliance, 'Pym' whose failures entice instead of repel," Jaynes rhapsodizes about this strange book at the beginning of one chapter, sounding like Humbert Humbert and nearly as far gone.

Yet Jaynes can't convince anyone else that in Poe's 'Pym' he has found the key to "Whiteness, as pathology and as mindset ... the primal American subconscious, the foundation on which all our visible systems and structures were built." Accused of neglecting the beat he was hired to cover, he insists that he's not "an apolitical coward, running away from the battle. I was running so hard toward it, I was around the world and coming back in the other direction."

And soon he is literally going around the world. Jaynes stumbles across a manuscript that suggests that Arthur Gordon Pym really existed -- which means that the island of Tsalal, a place so black even the water is colored, must exist, too. Determined to find this "great undiscovered African Diasporan homeland ... a society outside of time and history," he puts together an expedition. Its crew includes the ex-girlfriend he's been pining after for seven years (and the slick entertainment lawyer he didn't know she'd married), a gay couple who film their stagily heroic exploits for the Internet and his best friend, Garth, a laid-off city bus driver with a serious addiction to Little Debbie snack cakes. Their captain and leader is Jaynes' older cousin, Booker, a civil rights movement veteran with a dog named White Folks, who meets Jaynes downtown, sitting "in the back of the room staring intently at the front door, Malcolm X style, which considering we were in an organic juice bar was a little heavy for the scene."

The novel's early chapters, all set in America, are clever enough that I wouldn't have minded if Jaynes' ship had never sailed. Tracking down the descendants of Pym's racially ambiguous traveling companion, he stumbles across the Web page of one Mahalia Mathis, "a self-proclaimed "Singer, Actor, Poet, Novelist, Dancer, Actress and Noted Psychic Person.'" He attends a meeting of the Native American Ancestry Collective of Gary (Indiana), a confederation of wishful thinkers who, underneath their feather headdresses and buckskin, "looked like any gathering of black American folks." He tries to talk Garth out of his devotion to billionaire artist Thomas Karvel, "The Master of Light," whose uberkitschy paintings of English cottages look, in Jaynes' words, "like the view up a Care Bear's ass." (Garth defends his taste for these narcotic scenes by protesting "I got stress!")

Jaynes and company do finally set sail, embarking on a series of escapades that Garth summarizes as "Negroes on Ice." Johnson's novel evolves into a full-fledged and fiendishly inventive inversion of Poe's, a series of bizarre encounters I can't bring myself to spoil, each one more deliciously pointed than the last. Suffice to say that they include death-defying treks across the permafrost, underground caverns, chases, multiple betrayals and even a climactic explosion -- also, be aware that matters of great import will hinge on Garth's stash of Little Debbie cakes.

"Pym" departs from its 19th-century inspiration in more than just the way it repurposes motifs of blackness and whiteness: Unlike "The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket," it is hilarious. (Much of this is due to Garth, who deserves a bust in the comic sidekick's hall of fame.) It's also a novel that doesn't soft-pedal the bitterness instilled by slavery and its racist legacy yet avoids lapsing into bitterness itself. It is a work filled with chagrined realizations, beginning with its very premise: that a fed-up black man might find his promised land in the pages of a book by a half-crazy, pro-slavery white guy. Nothing can be truly separated from that which is conceived of as its opposite. In Johnson's vision, the races are running away from each other so fast, they end up circling the globe and colliding again on the other side.

Shares