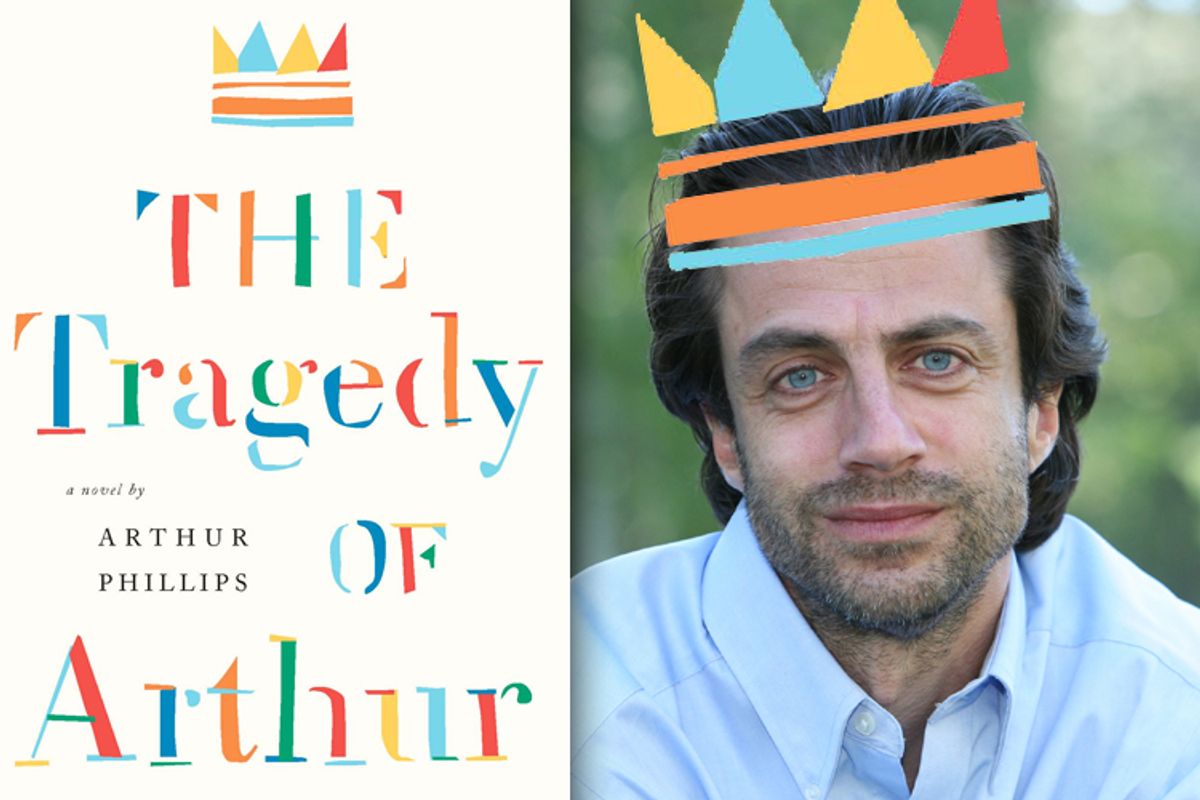

Arthur Phillips may or may not resent Shakespeare; it's hard to say for sure. But "Arthur Phillips" certainly does bear a grudge against the bard. Phillips is the author of four novels, including the sparkling debut, "Prague," and Arthur is a character in the most recent of them, "The Tragedy of Arthur." Arthur shares much of his creator's history: He's also the author of a novel titled "Prague" and has the same editor, agent and publicist as the real-life Phillips. But presumably the real Phillips is not the son of a small-time con man and the reluctant editor of a play experts have anointed as a long-lost work by Shakespeare.

As a rule, I'm leery of novels in which one of the characters has the same name as the author. Once upon a time, this seemed a clever gambit, calling attention to (among other things) the too-common tendency for readers to confuse novelists with their creations. By now, however, it's gotten a bit stale, and provokes many readers into rolling their eyes and muttering darkly about "postmodern tricks."

Nevertheless, "The Tragedy of Arthur" earns an exemption from such skepticism. This is a novel about authorship -- real, false and contested -- yet it's far from the sort of arch and arid exercise in formalist tail-swallowing that most people think of when they refer to "postmodern tricks." The novel is, indeed, a tragedy of authorship, but it is also the story of a man whose self-inflicted, tragicomic woes are as affecting and wincingly believable as those endured by the hero of any conventional fiction. That Arthur's spectacular crash-and-burn comes nestled in a web of ingenious and very funny literary allusions only makes it that much more of a treat.

Here's the premise: Arthur's narration is the introduction to the play, which makes up the final third of the novel (and is a fine Shakespearean pastiche). Although he once (briefly) believed it to be genuine, he's now convinced it was forged by his father (also named Arthur Phillips) -- no matter what forensic and literary scholars say to the contrary. Trapped in an elaborate legal snare that makes it impossible for him to withdraw the thing from publication, Arthur has, however, retained the right to force his disillusioned introduction into the book and to bicker in the footnotes with the scholarly editor retained by his publisher.

Fuming, Arthur explains how he found himself in this excruciating situation. He describes an early childhood of idyllic companionship with his twin sister, Dana, and his charming father, who beguiles him with a telescope that shows people on Saturn looking back at the boy with their own telescopes. Later, he enlists both children in creating bogus crop circles in a farmer's field. The father portrays his deceits as a campaign to replenish "the world's vanishing faith in wonder," but since he also applies his forgery skills to making a living, he ends up doing several stints in jail, breaking his daughter's heart, ruining his marriage and enraging his son.

"I loved him without reservations until reservations were required," Arthur explains, but the truth is a bit more complicated. Even before the first arrest, he was jealous of the bond between his father and his sister, cemented by their shared adoration of Shakespeare, a writer who leaves Arthur cold. Every so often, the disgruntled son takes a break from his narrative to rant about bardolatry, which he derides as "a trick of perspective, a rolling boulder of PR, a general cowardliness in us, a desire for heroes and easy answers," and it must be said that some of his jibes deliver palpable hits. Does Shakespeare epitomize what we find great in literature, Arthur asks, or have we cut our conception of greatness to fit his form because we want so badly to believe that "one guy had it all"?

And now a word about the extracurricular attractions of "The Tragedy of Arthur." Surely the modern world's most extravagant bardolater is Yale professor Harold Bloom, who, as Arthur puts it, "traveled all the way to the maximalist and insane thesis that Shakespeare invented how people now live, communicate and think." What Arthur doesn't explain is that Bloom is perhaps most famous for "The Anxiety of Influence," a book that advanced the theory that every great writer is locked in an oedipal struggle with the great writers of the previous generation and that these competitive feelings fuel artistic inspiration. Arthur is no exception. "You're the first person ever to suffer from a double oedipal complex," is how Dana puts it. "And one of your dads is four hundred years old."

But if the fictional Arthur fantasizes about surpassing Shakespeare, the real-life Phillips has a different artistic daddy in mind, a writer whose name is never mentioned in "The Tragedy of Arthur," although he is referred to once, obliquely. Phillips' novel is, of course, a tribute to Vladimir Nabokov's "Pale Fire," which takes the form of an annotated long poem that is eventually submerged in the ravings of its demented and homicidal editor. Phillips' Nabokovian flourishes are on ample display in "The Tragedy of Arthur," as when he compares a snail to an "ornate, restless 2" or worries that his father's forgery will find favor with an academic champion, "some tenure-famished conniver ready to authenticate to make a name."

But I'll stop there, for fear that this will come to resemble Mary McCarthy's famous review of "Pale Fire," a piece titled "A Bolt From the Blue," that is -- in my opinion -- over-celebrated. The review consists almost entirely of a listing of Nabokov's literary references, and amounts to little more than McCarthy showing off her parochial-school erudition. (Literary critics, too -- even the female ones! -- have their oedipal grudges.)

Besides, you don't need to know all this for "The Tragedy of Arthur" to work as a novel about a man whose refusal to believe that he is sufficiently loved causes him to alienate the people who really do love him. Like a lot of us, Arthur half-recognizes what he's doing, but just can't stop himself. "I refused to resemble my father in any way," is how he describes his attitude at one crucial juncture, and of course that's exactly whom he ends up resembling. There's irony in that, but not the facile, sterile irony that many people think of when they talk about postmodern tricks. Instead, this is the hard-earned irony of lived experience, and if it sometimes laughs, that doesn't mean it hasn't known its share of tears.

Shares