Fact No. 1: That “ObamaCare” and its individual mandate represent a freedom-killing abomination is an article of faith to today’s Republican Party base.

Fact No. 2: Mitt Romney, who entered the 2012 cycle as the GOP’s nominal White House front-runner, championed, signed into law and spent years defending a universal healthcare program in Massachusetts that included an individual mandate and that served as the model for “ObamaCare.” Moreover, Romney has a lengthy history of supporting the mandate concept, and as recently as December 2007 was holding up his own Massachusetts law — mandate and all — as a blueprint for other states, predicting that eventually “we’ll end up with a nation that’s taken a mandate approach.”

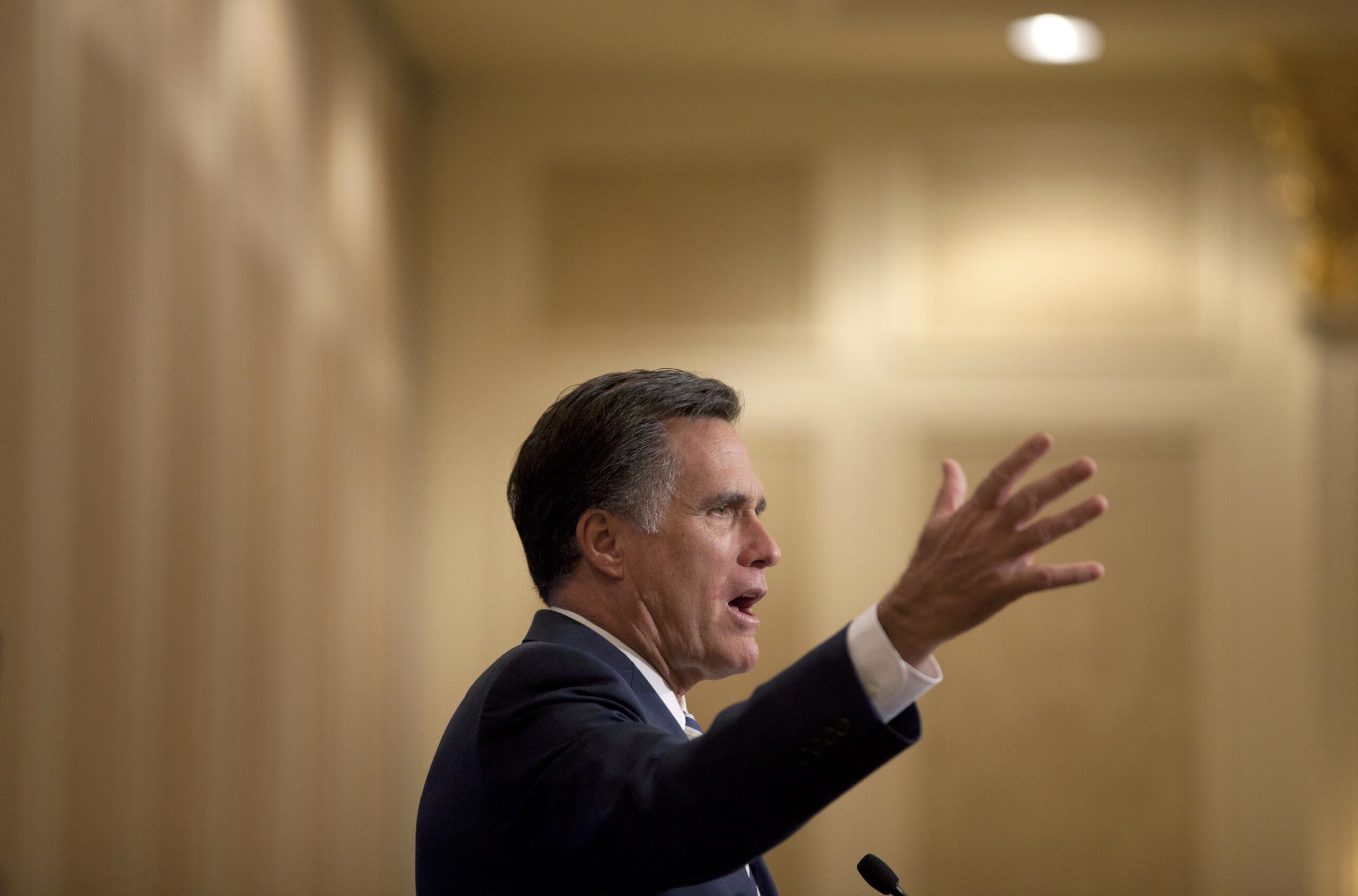

This certainly seems damning for Romney. He has tried and failed for the past year to reconcile these two facts, and he’s set to take yet another pass on Thursday, with a major speech on healthcare at the University of Michigan. Indications are that he won’t radically alter what has been his basic message on the subject — meaning that he won’t renounce the Massachusetts law but will suggest (without much specificity) that it was flawed, and that he will again demand that “ObamaCare” be repealed and that healthcare be left to the states. (This was the theme of a USA Today Op-Ed penned by Romney and released online late Wednesday afternoon; it didn’t once mention the word “mandate.”)

The pundit consensus is that this approach will prove thoroughly inadequate. As Jonathan Chait put it a while back:

Conservatives are dying to run a 2012 campaign based on full-throated opposition to the Affordable Care Act, repeal of which they have convinced themselves (through endless selective cherry-picking of polls) is wildly popular. They understand perfectly well that Romney would find it very difficult to run a campaign like that.

Thus, the thinking goes, Romney’s best — and only — chance of overcoming his healthcare problem would be through declaring the Massachusetts law a failure, expressing his remorse for signing it, and running as a born-again anti-mandate crusader. But given that he recently authored a book called “No Apology” and that he’s taken enormous grief for walking back so many other positions on major issues, Romney is (at least for now) understandably reluctant to declare that his signature achievement as governor of Massachusetts — something he insisted for years he was quite proud of — is actually a total and complete disaster.

As irrational as it seems, he may actually get away with it.

Yes, from a strictly rational and logical standpoint, it should be impossible for Romney to win the 2012 GOP presidential nomination after imposing an individual health insurance mandate on millions of American citizens and refusing to say he was wrong for doing so. But that’s OK, because the right’s fanatical opposition to “ObamaCare” is rooted much more in reflexive, emotion-driven resentment of President Obama and his fellow Democrats than in a rational, logical assessment of the law.

The fact that Romney is in this jam is proof of this. When he signed the Massachusetts law in April 2006, he was in full-on pander mode with the national GOP base. If a policy was anathema to the right, he was opposed to it — and if there’d been any indication that endorsing a mandate would significantly affect his ability to get to John McCain’s right, Romney wouldn’t have done it. (Don’t forget, he made sure to bring a representative of the Heritage Foundation to the bill-signing ceremony.) The mandate concept has always been opposed by a fair number of conservatives, but in 2006 it had plenty of casual support from Republicans (who saw it as friendly to the private sector and encouraging of individual responsibility) and wasn’t particularly controversial in GOP circles. It didn’t, for instance, prevent Romney from winning the support of South Carolina’s Jim DeMint, perhaps the most conservative member of the Senate; DeMint, in fact, publicly defended Romney’s program.

But now, of course, DeMint and most other conservatives who were supportive of (or who weren’t instantly offended by) mandates a few years ago have changed their tune — a posture that grew out of their instinctive opposition to Obama and his agenda. DeMint is walking away from Romney, now, and he’s not alone, but this entire evolution ought to be instructive about the psychology of the right: A deep-held principle — that a healthcare mandate is a freedom-killing violation of our nation’s sacred founding values — has emerged from a fundamentally emotional reaction to a Democratic president. Putting the true believers (i.e., conservatives who hated mandates even before 2009) aside, most of the passionate arguments Republicans have offered against “ObamaCare” represent either a product of this emotional reaction or an effort to cater to it.

How does this help Romney? It means that his cover story on healthcare doesn’t necessarily have to be rational for GOP elites to ultimately rally around him and to help sell him to rank-and-file GOP voters. It may be enough to cater to the basic sensibility that now animates the right (“ObamaCare must be repealed!”) and to gloss over his own Massachusetts record with confident gobbledygook about states’ rights and … whatever else he offers by way of a cover story. He needs GOP elites to decide that he’s their best bet as a nominee. If they do that, then they’ll create all sorts of rationalizations for backing him — and ignoring “RomneyCare.”

Granted, this might not work at all. Certainly, there will be plenty of influential conservatives on whom it will never work. But a somewhat useful parallel can be drawn here to John McCain, who crossed the GOP base on immigration in the run-up to the 2008 primaries. The GOP base of 2007 and ’08 was just as passionate about “amnesty” as it is about “ObamaCare” now. After watching his campaign nearly collapse in the spring of 2007, McCain ended up modifying his immigration stance, backing off support for a pathway to citizenship for undocumented workers and emphasizing stepped-up border enforcement. But it was hardly a convincing transformation. Even after abandoning his bill, McCain continued to send profoundly mixed messages on the subject. He never offered the dramatic, full-throated apology that many say Romney needs to provide now. And he didn’t exactly win over the opinion-shaping conservatives who cared most about immigration; they continued to accuse him of backing amnesty.

But in the end, McCain did just enough to win. His chief GOP rivals all had liabilities of their own, and as the first primaries and caucuses approached, conservatives who had previously denounced McCain and written him off for dead began uniting around him. They’d discovered that, for different reasons, they didn’t like their other options and they concluded that McCain was electable in the fall. Then they began making their arguments. A pivotal moment for McCain, for instance, came when the Manchester Union Leader endorsed him a month before the New Hampshire primary. On paper, McCain had no business winning the paper’s support; even before the immigration storm it had disliked him intensely. But they went with him anyway. So did other conservatives. As the late Robert Novak described it in a December 2007 column:

This scenario does not connote a late-blooming affection for McCain among the party faithful. Indeed, he remains suspect to them on global warming, stem-cell research, tax policy and immigration controls, not to mention his original sin of campaign finance reform (with authorship of the McCain-Feingold Act). Rather, his nomination would result from him being the last man standing, with all other candidates falling. Rudy Giuliani’s baggage is getting too heavy to carry. Fred Thompson never got started. Huckabee’s Republicanism is even less orthodox than McCain’s and seems unviable beyond Iowa. Romney is burdened with anti-Mormon prejudice and the accusation he is “plastic.”

Romney can potentially benefit from the same phenomenon. His GOP rivals — just like McCain’s — all have their own shortcomings. Tim Pawlenty is trying as hard as he can and he makes considerable sense on paper. But conservative activists and opinion-shapers have been very slow to sign on; his utter blandness may keep them away for the entire campaign. (In a way, I’m tempted to compare him to Phil Gramm, who made just as much sense on paper in the run-up to the 1996 GOP primaries — but who also turned off activists and opinion leaders and never got off the ground.) Mitch Daniels is also bland and has already aroused suspicions from cultural conservatives with his call for a “truce” on social issues. And so on. Just like they finally came back to McCain in late 2007 and managed to rationalize it, GOP elites may end up doing the same with Romney. Not all of them, of course — but this was the case with McCain, too. Rush Limbaugh, for instance, urged his listeners to resist McCain all the way to the end.

But we’ll know Romney has survived if December rolls around and, say, Sean Hannity announces on his Fox News show: “I have to say, I don’t agree with what he did in Massachusetts, but the bottom line with Mitt Romney is that we’d get rid of ObamaCare …”