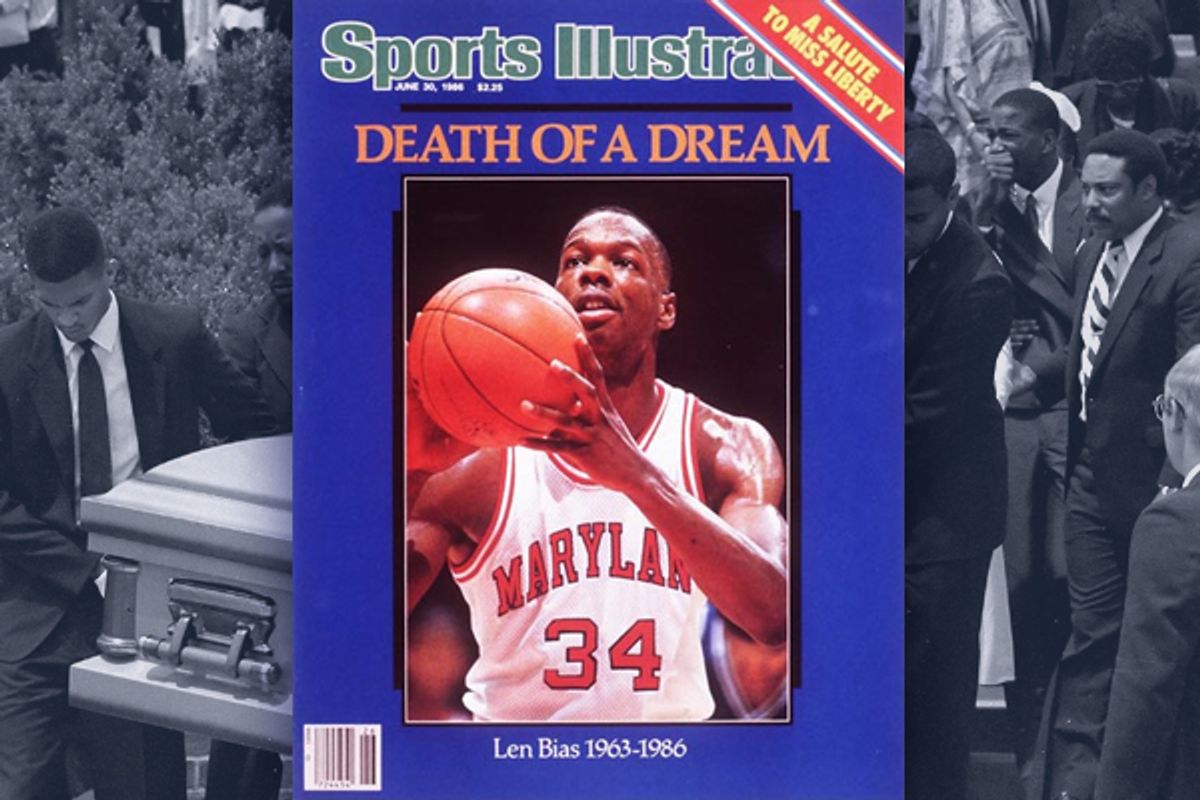

On June 19, 1986, 25 years ago Sunday, University of Maryland basketball star Len Bias died of cocaine intoxication. Many believed the 6-foot 7, 220-pound small forward possessed a level of talent equal to that of Michael Jordan, and only two days earlier he'd been selected as the No. 2 overall pick in the NBA draft by the reigning champion Boston Celtics.

In Ronald Reagan's America, Bias instantly became the poster child for what could happen to anyone who didn't just say no. His sudden, shocking death dominated the headlines and unnerved millions of Americans, who were told that the cardiac arrhythmia he suffered was the result of casual, one-time experimentation with drugs. "Leonard's only vice," his college coach, Charles "Lefty" Driesell, had declared just days earlier, "is ice cream."

Responding to this outpouring of grief and fear, Congress promptly passed (and Reagan signed) the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986. In their haste, they may not have fully grasped what they were doing.

The law has resulted in 25 years of disproportionately harsh prison sentences for defendants who are disproportionately black. It called for felony charges and mandatory minimum prison sentences for anyone caught with even a small amount of cocaine; inexplicably, it triggered the mandatory sentences for crack cocaine possession at 1/100 the amount of powder cocaine. Rather than rooting out the traffickers, it filled the country’s jails with blacks and Hispanics, who in some cases serve more time for possession than convicted murderers. It was only after '86 that the number of blacks surpassed the number of whites in prison for the first time, and many of the offenders who were picked up that year are still locked up.

Richard Nixon formally declared America's war on drugs 40 years ago, but the 1986 law was the first significant piece of legislation related to it. To mark the 25th anniversary of the tragedy that led to the drug war as we now know it, we spoke with Eric Sterling, who served as counsel to the House committee that drafted the '86 law. Now president of the Criminal Justice Policy Foundation, he discussed the legislative frenzy that followed Bias' death and its consequences, and what might have been if Bias had lived.

Remind us of Len Bias the rising basketball star, before he became a symbol of the drug war.

Len Bias grew up in the D.C. area where he was a high school basketball star. By 1986 he was an All-American at the University of Maryland, which was one of the top basketball programs in the country. He was a player on the same scale as a Michael Jordan -- they were essentially contemporaries.

And then what happened?

After the NBA draft, he caught a plane back to Washington -- he was still living on campus at the time. He was celebrating the signing with some of his friends, they were drinking, and then one friend came over and they started snorting cocaine. He had a seizure in the early morning and someone called 911, but before the morning was over he was dead. That morning the newspapers still had stories about his signing and pictures of him at the draft, but if you turned on the radio or TV there were stories that he was dead. It was a tremendous scandal.

So it was a tragic, sensational story, but Congress doesn't jump on every headline like they it here. Why did they seize on this one?

Any member of Congress who watched sports in the '80s had seen Len Bias dozens of times driving to basket, making these incredible shots, blocking and rebounding -- he was a hardworking, effective and beautiful athlete. The Boston Celtics drafted him and they had just won the NBA championship the year before. Len flew up to the Boston Garden for the draft and appeared at a press conference where there were something like 25 TV cameras around him for the signing. He had also just signed a multimillion-dollar shoe contract with Reebok. He was the biggest college basketball star of his time, so aside from the sports angle, this was just a big news story.

And it coupled well with another big news story of '80s, which was the cocaine problem.

That’s right. There was this growing problem of crack cocaine and there was a lot of the violence that surrounded the trade that really increased the stigma of it. In 1984, Reagan was able to convince voters that he was stronger than Walter Mondale on the issues of drugs and crime, so the Democrats were looking for a way to regain control of that story. [House Speaker] Tip O’Neill was about to retire, and as a swan song he thought he could help the Democrats regain control by getting tough on these issues.

And it just sort of escalated from there?

It became the sole focus of legislative activity for the remainder of the session on both sides of the aisle. Literally every committee, from the Committee on Agriculture to the Committee on Merchant Marine and Fisheries were somehow getting involved. Suddenly, the Len Bias case was the driving force behind every piece of legislation. Members of Congress were setting up hearings about the drug problem and every subcommittee chairman was looking to get a piece of the action. They were talking about Len Bias at every press conference and it was all tied together -- the Len Bias tragedy and the potency of drugs and this evil that was killing America’s youth. He became shorthand, a high-profile symbol for all of these issues. People were shouting about how crack cocaine was the most addictive or dangerous substance to ever exist, and one lawmaker was calling for the death penalty for some drug-related offenses. It was hyperbole piled on top of exaggeration.

And the story that was pushed in the media made it even scarier?

Bias was a clean-cut guy. To be that kind of an athlete and to operate at that level he had to be. Had he used cocaine before? Possibly. But there wasn’t any evidence that he was an addict. So there was this idea that if it can happen to this healthy kid, it can happen to anyone. The story became that if you try it even once, it can kill you. That was the story of Len Bias and cocaine.

How did the legislation come together?

Usually when you want to introduce a new bill, you sit down and carefully write the policy. Are we clear on what the implications are? You write a draft and maybe circulate it around for ideas. You ask federal judges, prisons, prosecutors, U.S. attorneys, the DEA, law professors, sentencing commissions, criminal defense lawyers and the ACLU how it will affect things. You have hearings. All of this was skipped [for the drug sentencing bill]. Both sides were trying to be quicker and tougher than the other.

So the DEA came up with numbers to define high-level trafficking, but a congressman from Kentucky said he would never be able to use the law because they didn’t have trafficking that high in his area. So we needed new numbers. Nobody stopped to say, "But Louisville isn’t Miami or Hollywood or New York. You should be lucky you don’t see this in Louisville." Suddenly, these numbers just wouldn't work -- we needed "better" numbers. So I called a very respected narc named Johnny St. Valentine Brown, whose nickname was Jehru, to detail to the committee what the numbers should be on minimum trafficking violations.

So a narc was responsible for the 100-to-1 crack-to-powder ratio?

Yes. And later he turned out to be a perjurer and went to federal prison. He had lied for years about graduating from Howard University’s School of Pharmacy and being a pharmacist. In preparation for his sentencing he provided some letters attesting to his good reputation from various figures in D.C., including judges. It turned out he had forged the letters he was submitting to the court to get a more lenient sentence!

Anyway, there was no conversation to determine if crack was even more dangerous than cocaine, or what quantity a mid-level crack dealer might carry in comparison to a mid-level cocaine dealer. It was a seat-of-the-pants judgment from this one narc about what the drug trade in one part of the country might have looked like at that moment in time.

That’s insane.

And those were last-minute items thrown into the first bill that was passed by the House. At the time, the Senate was controlled by Strom Thurmond and the Republicans. They looked at it and said: "OK, well if the Democrats have a sentence of five years to 20 years, let's up it to 10 years to 40 years. And if the Dems say 20 grams, we’ll make it 5!” Nobody looked at the proper ratios based on how harmful it was. It was completely detached from science. Nobody could say that crack was 100 times more dangerous than powder.

What were the social effects of these laws?

In 1986 the federal prison population was 36,000. Today it’s 216,000. And in the 25 years since, more than half of federal prisoners are brought in on drug charges. The prison population is disproportionately black and Hispanic. The federal government does about 25,000 cases a year and only one out of four of those defendants is white. Also, it’s widely believed that crack cases are mostly minorities, while the powder cocaine cases are mostly white, but that’s a myth. It’s true that only one in 10 crack cases are white, but the overwhelming majority of powder cocaine defendants are still black or Hispanic.

From that angle it certainly looks like intentionally racist legislation.

There were all of these mythologies about how Congress did this intentionally because powder was only used by whites. The way it was put together wasn’t racist, it just wasn’t thought out.

But the other thing that was skewed was that the Department of Justice was supposed to be focusing on high-level traffickers. You look at global trafficking -- this stuff is coming in on boats by the ton, but more than a third of federal cases involve less than an ounce of crack cocaine.

So the federal government is looking at insignificant local cases and handing out long sentences to defendants that are predominantly black or Hispanic. No matter what the intentions were in 1986, if these measures had been carried out by a local D.A. instead of the federal government, that D.A. would be indicted for violating civil rights laws.

Have the laws changed at all in the last 25 years?

Attorney general after attorney general has utterly failed to say the first word on this. The drug czars continue to ignore the fact that people of color are being given inconceivable sentences. It’s outrageous, but it can be a tricky thing. I remember Charlie Rangel proposed the Crack Cocaine Equitable Sentencing Act, but those words don't mean anything! How are you going to convince people to vote for something when it sounds like the Let Crack Dealers Out of Prison Early Act? You have to call it something like the Cocaine Kingpin Punishment Act.

But anyway, in 2010 they passed the Fair Sentencing Act, which raised the amounts that triggered minimum sentencing, and lowered the crack cocaine ratio from 100-to-1 to 18-to-1.

Is that ratio still just as arbitrary?

Yes.

What other changes would you still like to see?

The Department of Justice is the most powerful law enforcement agency in world. They can use the CIA and the military, they can take on money laundering investigations and look at wire transfers at every bank in the world. If they were focused on the drug trade instead of helping sheriffs break down doors, we would see a big change.

Another change could be done administratively. The attorney general could tell attorneys not to make it a federal case if it’s under 200 kilos, unless it involves a homicide or intimidation of a witness or something like that. There are 1.7 million state and local drug arrests every year and 300,000 state felony convictions. We’re already prosecuting crack dealers all over the country. The feds are just piggybacking on the local guys.

Len Bias would be 48 this year. How would the world be different if he hadn’t died of a cocaine overdose in 1986?

The world would be completely different. Hundreds of thousands of people would never have gone to jail if Len Bias had not died.

This story has been updated to reflect the following changes:

It was originally reported that Bias flew to Madison Square Garden for the draft. This has been changed to the Boston Garden. Also, it was not the Senate Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition and Forestry involved in the legislation, but rather the House Committee on Agriculture.

Shares