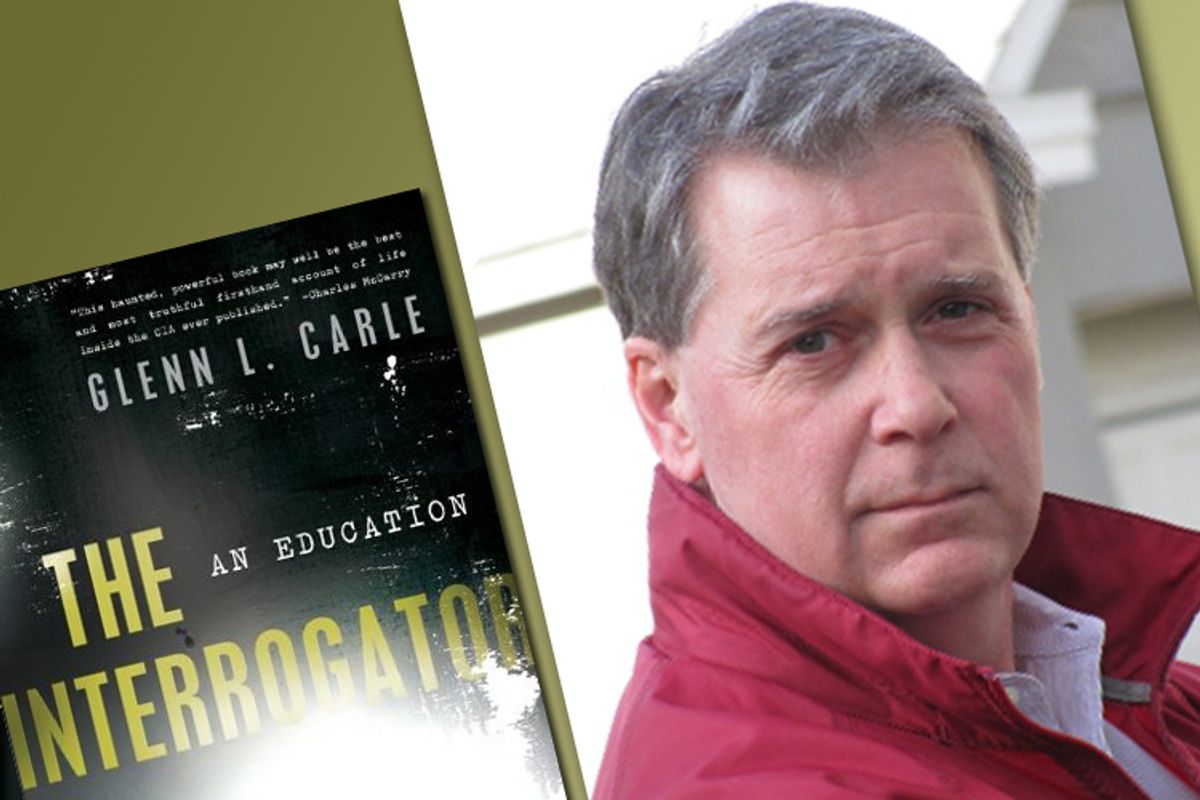

"The situation had become Kafkaesque," writes Glenn Carle toward the end of "The Interrogator: An Education," his new memoir. Boy, he ain't kidding; the author of "The Trial" and "The Metamorphosis" would have appreciated this narrative on any number of levels. Carle worked for the CIA for 23 years, in Africa, the Balkans and Latin America, among other locales, but the focus of his book is the several-month period he spent questioning a suspected leader of al-Qaida in two countries he is not permitted to name.

There's quite a lot Carle isn't allowed to say in "The Interrogator." Many lines and words on these pages have been masked with black bars to indicate what "the Agency" forbade him to publish. "I have written this book literally a dozen times over," the author notes in his afterword, explaining that he was willing to address "legitimate" CIA concerns when it came to revelations about its "sources and methods."

But such objections were, as Carle makes abundantly clear, amply mixed with ludicrous pettifoggery and ass-covering. This annoyed him enough that he decided to leave in the redacted bits, complete with black bars, and add the occasional withering explanatory footnote, like one that reads: "Apparently the CIA fears that the redacted passage would either humiliate the organization for incompetence or expose its officers to ridicule; unless the Agency considers obtuse incompetence a secret intelligence method."

Warning: A Severe Acronym Advisory is in effect for the next paragraph and for much of "The Interrogator." Carle was a veteran CO (case officer) who worked in the DO (Directorate of Operations, aka, where the action is), when he was invited to do a TDY (temporary duty) interrogating a HVT (high value target) being held by authorities in a Middle Eastern nation friendly to the U.S (I'm guessing Jordan). This was in 2002, and despite being one of the best speakers of "the language" (presumably Arabic) the agency had on staff in the scramble following 9/11, he was doing administrative work. A year earlier, Carle had made a dumb mistake during a period of turmoil in his home life; taking this assignment was his big chance to get back in the game.

This back story serves to indicate how high the stakes were for Carle, and therefore how much he risked, when, months later, he tried to tell the agency that the prisoner he'd been questioning, whose mistreatment ("what some will consider torture") he was obliged to condone, was largely innocent. This man -- known by the code name CAPTUS -- was, Carle became convinced, not even a member of al-Qaida, let alone a kingpin. The luckless fellow had played roughly the same role as "a train conductor who sells a criminal a ticket." Any further details Carle chose to relate on CAPTUS' activities and the "enhanced interrogation" techniques used on him by persons unknown have been obscured by CIA censors. (Confidential to the Agency: This makes the latter seem even more vile than they probably are.)

Carle blames multiple factors for this horrific situation, from the cluelessly belligerent interrogator he replaced through the higher-ups who were overly invested in what appeared to be "one of the premier coups and cases in the administration's War on Terror." However, the greatest responsibility, in his opinion, originates with that "small number of senior officials who drafted the legal rationalization for the coercive interrogation methods, and the government officials who ordered them to do so." We all know who they are.

And they were wrong -- morally and practically. Carle firmly believes that coercive methods don't work, and that they deliver less intelligence, and of poorer quality, than the techniques outlined in his bible, something called the KUBARK manual. (Parts of this CIA handbook were regarded as "controversial" back in the 1980s, and the fact that it was considered too mild by the Bush administration is sobering.) He contends that it is always a carefully built (although, of course, manipulative) relationship between the prisoner and the interrogator, rather than fear and pain, that produces the most and best results. Recent events seem to confirm that view. The intelligence used to target and kill Osama bin Laden is said to have been obtained through the psychological methods recommended by KUBARK, after torture fell short.

A lot of "The Interrogator" recounts Carle's frustrated attempts to change CAPTUS' status, and in particular to keep him from being sent to a secret CIA prison into which the detainee seemed likely to vanish forever. He illustrates how difficult it can be to swim against the current of institutional inertia, and how his decision to work internally and diplomatically (the only way, he believed, to have any real effect) left him feeling more and more implicated in actions he saw as both illegal and un-American. Although Carle had always embraced the challenge of working in a morally ambiguous "gray world" -- where he was called upon to lie and scheme in order to serve his country -- the CAPTUS case was categorically dark, and his experience with it permanently damaged his faith in the agency.

For Carle did have faith in the CIA, believing it to observe a certain brand of honor and to be a force for good in the world. From an old Massachusetts family, Harvard-educated and fond of reading Lucretius in nightclubs, he emerges as an odd and admirable, if not always entirely likable, character in "The Interrogator." Witnessing this prickly, rigidly upright man trying to wrest meaning from his bleak dilemma becomes the most compelling aspect of "The Interrogator." He occasionally gets broody, and drives off to explore the desert on camel back and talk philosophy with enigmatic locals. He looks at the "moonscape" surrounding the secret prison -- where CAPTUS does, ultimately, end up -- and quotes T.S. Eliot.

Carle's longest and most absurd struggle was simply to obtain CAPTUS' identification papers, which were languishing in the CIA station of the country where he was nabbed. This proved impossible -- there was never enough staff to courier the documents, despite the high-profile nature of the case. Eventually, Carle didn't even expect to get them, but kept making the request anyway. He was long past irritation or outrage -- even if his readers will not be -- and regards the pointless ritual as "perversely amusing." Like the man said: Kafkaesque.

Shares