Nicholas Meyer's bestselling 1974 novel, "The Seven Percent Solution," isn't mentioned once in "An Anatomy of Addiction: Sigmund Freud, William Halsted and the Miracle Drug Cocaine" by Howard Markel, but any of Markel's readers who have also read Meyer's highly entertaining Sherlock Holmes pastiche will think of it often all the same. The novel "reveals" that Holmes' "Great Hiatus" (the three years between his false death at Reichenbach Falls and his reappearance in "The Adventure of the Empty House") was actually a period of recovery from cocaine addiction after his treatment by the great Viennese therapist Sigmund Freud. The founder of psychoanalysis brought exceptional insight to bear in providing this cure; he once abused cocaine himself.

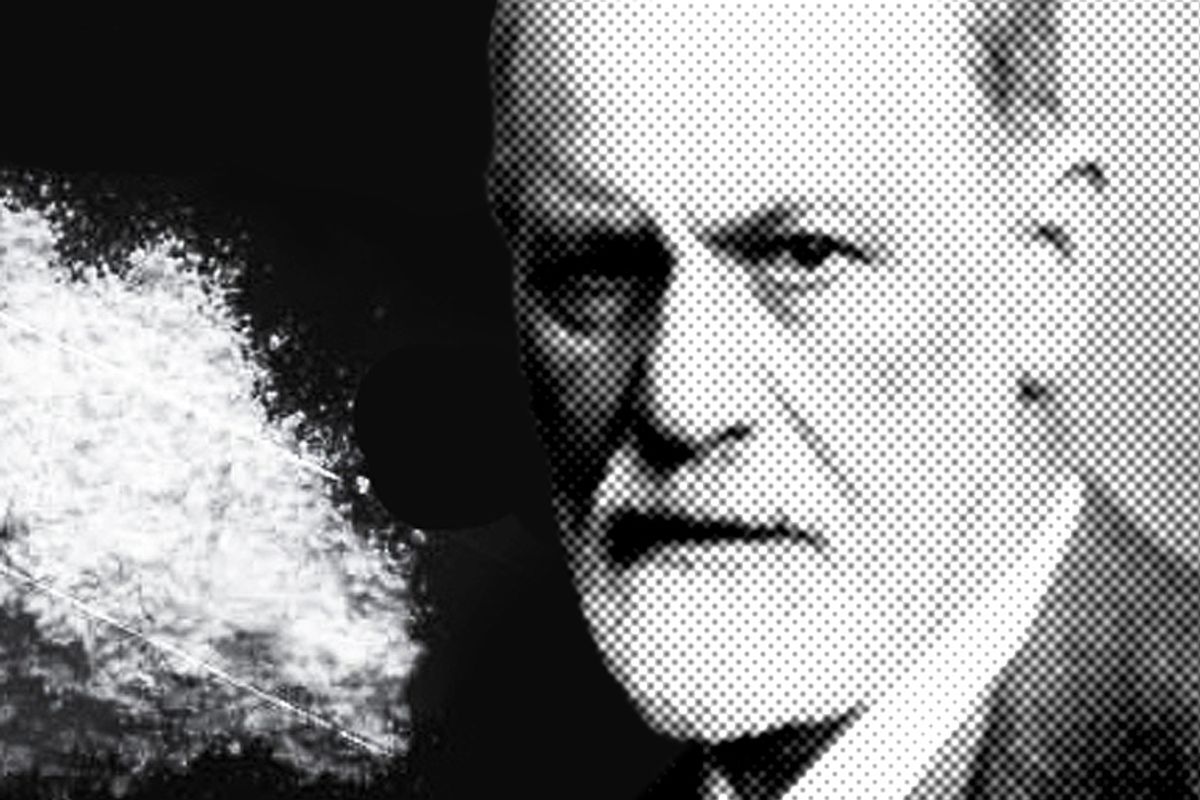

Markel's provocative book is a dual addiction biography of Freud and his contemporary, William Halsted, arguably the greatest surgeon of his time, a founding professor at Johns Hopkins Hospital and deviser of at least a half-dozen revolutionary surgical techniques and procedures still employed today, such as the use of rubber gloves. Both were unquestionably great men, but they also wrestled with dangerous drug habits that imperiled their work. Both sought to conceal or downplay their drug use and, as a result, information on that use and how, if at all, they managed to stop it is pretty sparse on the ground. If Meyer's novel is the story of a doctor investigating the psyche of a great detective, then "An Anatomy of Addiction" is the work of a doctor -- Markel is an M.D. and director for the Center of the History of Medicine at the University of Michigan -- who plays detective to understand the secret lives of two medical giants.

Halsted and Freud never met, and came from very different backgrounds, but they were both ambitious and energetic young doctors in the 1880s, when cocaine was being celebrated as a new wonder drug whose full potential had yet to be explored. In Austria, Freud wrote a prominent paper touting the newly isolated alkaloid as a treatment for morphine and opium addiction. He tested it on a close friend who had become hooked on the morphine he used to manage a chronic injury.

What Freud missed, and what became the drug's chief medical use for the next decade or so, was cocaine's value as a local anesthetic. Halsted, an indefatigable and daring young surgeon (he successfully removed his own mother's gall bladder on the family's kitchen table at 2 a.m., with his untrained father and siblings attending), was as eager to explore its possibilities as he was to adopt the new antiseptic protocols advocated by Joseph Lister. Like many doctors of the time, including Freud, he tested the drug's properties on himself, his colleagues and his students. "In a matter of weeks," Markel writes, "Halsted and his immediate circle transformed from an elite cadre of doctors into active cocaine abusers."

Halsted shot up; Freud snorted. Halsted was rich and well connected; Freud was close to broke and struggling to make a name for himself in a profession afflicted by expanding pockets of anti-Semitism. Freud by all accounts figured out how to give up the drug, while Halsted, Markel believes, would go on occasional binges throughout the rest of his distinguished life. At least twice, Halsted resorted to staying at a Rhode Island sanitarium to get clean. He also used morphine, probably daily. Behavior that many of his students and colleagues shrugged off as eccentricity -- lateness, incommunicado periods, a refusal to look people in the eyes (and thereby reveal his dilated pupils) -- were read by a handful of astute observers as signs that the drug use he'd supposedly abandoned before arriving at Hopkins was still going on.

Freud, on the other hand, seems to have entirely stopped using cocaine by the turn of the century. For the rest of his days he strove to downplay the effect it had on his life and work. Markel will have none of this, arguing that cocaine played a major role in Freud's friendship with Wilhelm Fliess, a general practitioner who espoused the crackpot theory that many physical and emotional problems could be cured by intensive surgery to the nose (with liberal applications of cocaine). Freud recommended one of his own patients to Fliess, who proceeded to disfigure and nearly kill the young woman in a case of flagrant malpractice. Freud made excuses for him.

The Fliess affair seems less a case of cocaine-induced incompetence than an example of Freud's propensity for stubbornly idealizing a particular friend to the point of delusion. Similarly, it took him far too long to admit he had understated the dangers of cocaine, even after he'd witnessed its eventual, disastrous effect on his morphine-addicted friend. All discussions of Freud are further complicated by the fact that the brilliance of his ideas and his writings was not mirrored in his therapeutic success rate. He was a major thinker, but an indifferent doctor. Far better to be his student than his patient.

For the most part, however, "An Anatomy of Addiction" is persuasive and engrossing. Markel is especially good at capturing the hierarchical, ultra-competitive, pressurized world of 19th-century medicine, with its revered masters and mentors presiding over students and young doctors desperately striving to make an impression and a reputation. Perceptively, he traces the birth of psychoanalysis to Freud's use of himself as an experimental subject in documenting the effects of cocaine. For the first time, Freud "incorporates his own feelings, sensations and experiences into his scientific observations."

Freud was always at his best when contemplating the subject of his own psyche. (His weaknesses, furthermore, often spring from a tendency to overgeneralize from it.) If his cocaine experiments nudged him in that direction, then perhaps we do owe some of the most influential ideas of the last century to the influence of Bolivian Marching Powder. More's the pity, then, that pride or fear or something else kept Freud from recounting how he kicked the habit.

Shares