Three weeks ago, a black candidate earned enough votes to advance to the run-off for the Democratic gubernatorial nomination in Mississippi -- the first time in the state's history this had ever happened in either party. And on Tuesday night, that candidate, Johnny DuPree, won the run-off, defeating a white businessman by 10 points, another historic first.

Now DuPree, the mayor of Hattiesburg, a small city where the population is split almost evenly between blacks and whites, will represent his party in the fall campaign against Republican Phil Bryant, who has served as Haley Barbour's lieutenant governor since 2007. The obvious temptation is to smile at this breakthrough in the heart of the Old Confederacy: This is what progress looks like, right?

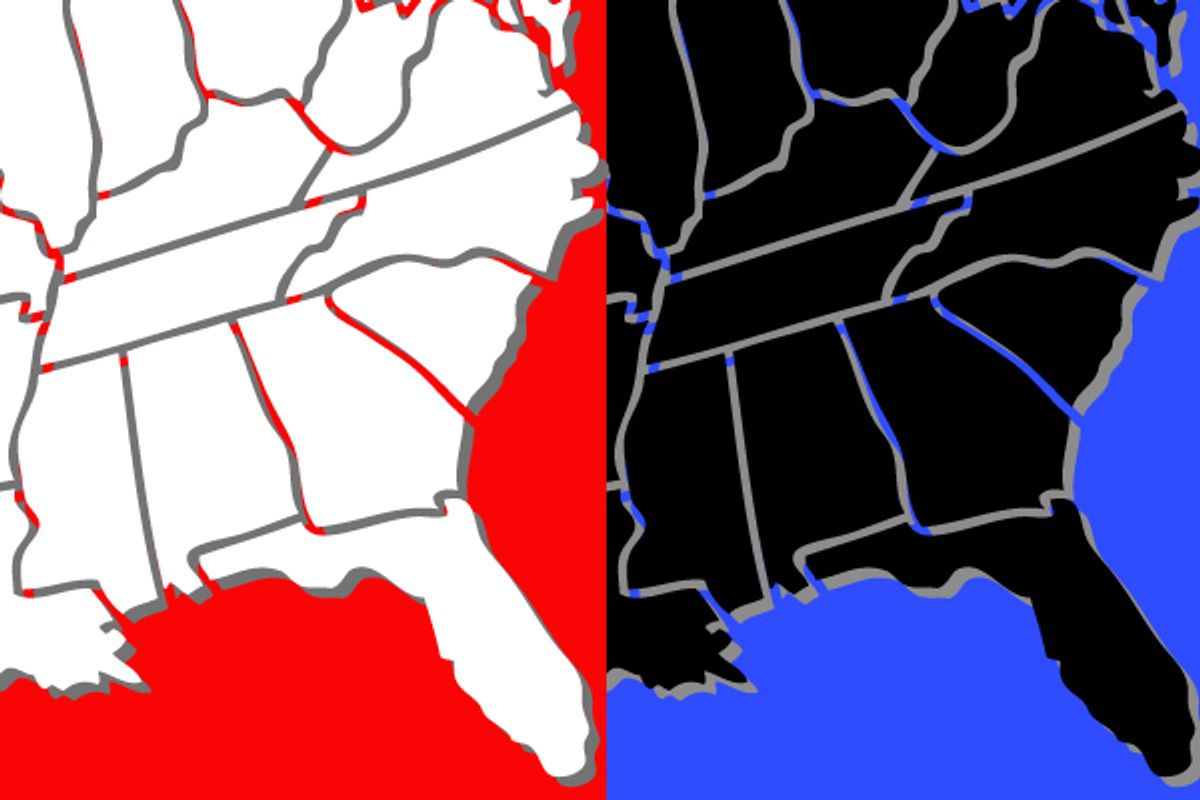

The reality, though, is far more complicated. While DuPree certainly deserves credit, it's hard not to look at his victory as the product of a rather depressing evolution of voting patterns in the Deep South, where race has increasingly become synonymous with party identification. It is this same evolution that will almost certainly doom him to a lopsided defeat in Mississippi this fall -- just as it dooms most Democrats, black or white, who run for statewide office in Dixie these days.

The story begins about a half-century ago, back when the right to vote in the South was the almost exclusive domain of white people. In those days, the Republican Party barely existed in the region. White Southerners had been raised on horror stories of the indignities visited upon their forebears by the Reconstruction that followed the Civil War, a project of Yankee Republicans. Through the middle of the 20th century, there was no more loyal component of the national Democratic coalition than the South. When, for instance, Franklin Roosevelt ran for reelection in 1936, he tallied more than 80 percent of the vote in six Southern states -- including 99 percent in South Carolina and 97 percent in Mississippi.

The shift came when civil rights emerged as a leading national issue, one that ultimately forced the Democratic Party to choose between pro-integration Northerners (led by urban leaders whose machines were increasingly dependent on black voters, many of whom had fled the Jim Crow South) and the reliable South. The fateful moment, if there was one, took place in 1964, when LBJ signed the Civil Rights Act and Republicans spurned the racially liberal Nelson Rockefeller for their presidential nomination, instead picking Barry Goldwater, who had joined the Southern Democratic filibuster of the new law. Dixie's swing in that fall's election was dramatic. Even as Goldwater lost in an epic landslide nationally, he carried five Southern states. His tally in Mississippi: 87 percent.

But the '64 results were only a hint of what was to come. Southerners did not begin checking off Republican names up and down the ballot overnight. For years to come, in fact, Goldwater's success looked more like an aberration, at least when it came to statewide and local elections. White voters remained emotionally connected to the Democratic identities they'd inherited and receptive to the Democratic candidates -- many of them conservatives who would today be recognized as Republicans -- they saw on their ballots. And in most pockets of the South, Republican organizations were only beginning to show signs of life. Except at the presidential level, the South remained an overwhelmingly Democratic region through the 1970s.

Which created what, in hindsight, looks like a magical era of racial and political reconciliation, with a wave of newly registered black voters flocking to a Democratic Party that Southern whites were still mostly loyal to -- and with politicians responding in kind. It was in this period that a classic Mississippi populist named Cliff Finch, who would tote his own lunch-bucket on the campaign trail, bragged of forging a "redneck-blackneck" coalition, a biracial union of working-class voters all responding to his attacks on Big Business. Finch won the governorship in 1975.

Four years later, a Washington Post reporter checked in on the race to succeed him and noted with surprise that both the Democratic candidate (William Winter) and the GOP nominee (Gil Carmichael) had seen fit to plead their cases before a group of black leaders:

The meeting was in a dingy gymnasium on the south side of Jackson, not far from Jackson State University. Much of the state's black leadership was there, wearing three-piece suits. Many, like Aaron Henry and Charles Evers, were veterans of some of the nation's most brutal civil rights battles during the 1960s, a time when the governor of the state, Ross Barnett, once said "The Negro is different because God made him different to punish him."

Mississippi politicians no longer attack blacks; they court them. And every white candidate for statewide office was at the meeting, each promising more brotherhood than the one before.

In the same article, a long-time Mississippi journalist was quoted as saying:

"This is the high-water mark in Mississippi politics. I've never seen two people of such quality in one race in this state. Nobody will be ashamed of whoever is elected.

"I've never been able to say that before. We've punished ourselves too long in Mississippi by electing buffoons, racists, negativists and people who have become governor by attrition."

Such a high-minded contest was possible because both parties were in a state of flux. A racial progressive could win a statewide Democratic nomination with the support of new black voters, white liberals and some rural whites, then prevail in the fall thanks to the lingering partisan loyalty of other white voters. At the same time, a fair number of white conservatives had switched from the Democratic Party to the GOP, but their numbers weren't yet big enough to prevent a moderate Republican from winning a statewide nomination.

This was all essentially a fluke, though. Ronald Reagan's 1980 triumph, after a campaign in which he'd expressed his reverence for "states' rights" in a speech at Mississippi's Neshoba County Fair (the same county where three civil rights activists from the North had been murdered by Klansmen in 1964), helped cement the South as a thoroughly Republican region at the national level. State and local Republican organizations in the region grew stronger, conservative Democratic officials began switching parties, and voters slowly replaced retiring Democratic officeholders with fresh-faced Republicans. Southern whites came to regard the South's version of the Democratic Party as a mere extension of the national Democratic Party -- a haven for liberals and minorities.

There would be the occasional good year for Democrats in the South, but the evolution continued through the '90s and the '00s. Last year's midterm elections were a particular milestone, with the region's white Democratic congressmen all but wiped out and Republicans claiming a majority of Southern state legislative chambers for the first time since Reconstruction. It has taken decades, but white loyalty to the Democratic Party has all but vanished in the South, and today -- particularly in the Deep South -- race has emerged as one of the easiest predictors of a voter's partisan leanings.

Mississippi may be the most dramatic illustration of this. For instance, in the 2008 election, John McCain carried the state by a 55 to 44 percent margin. But the racial divide that produced that result is staggering: an 88-11 percent spread for McCain among whites, and a 98-2 percent margin for Obama among blacks. Nor was the gap appreciably narrower in 2004, when John Kerry ran against George W. Bush. Increasingly, this same divide is coming to define statewide contests in Mississippi. When he unseated Democratic Gov. Ronnie Musgrove (who had been celebrated for his supposed ability to keep rural white voters in his party's fold), Haley Barbour earned nearly 80 percent of the white vote, and he did even better in his 2007 reelection victory. It wasn't until 1991 that the state elected its first post-Reconstruction Republican governor (Kirk Fordice), but the only victory for Democrats since then was Mugrove's in 1999 (when he earned less than 50 percent of the popular vote and was elected by the state legislature).

And there's no reason to think that DuPree will put an end to the GOP's dominance this fall. There are many reasons why he's the heavy underdog against Bryant, but the simplest may be this: Five decades after desegregation, it is more possible than ever for a black candidate to win a Democratic nomination for a major office in the Deep South -- but just as impossible as ever for that candidate to actually win the election.

Shares