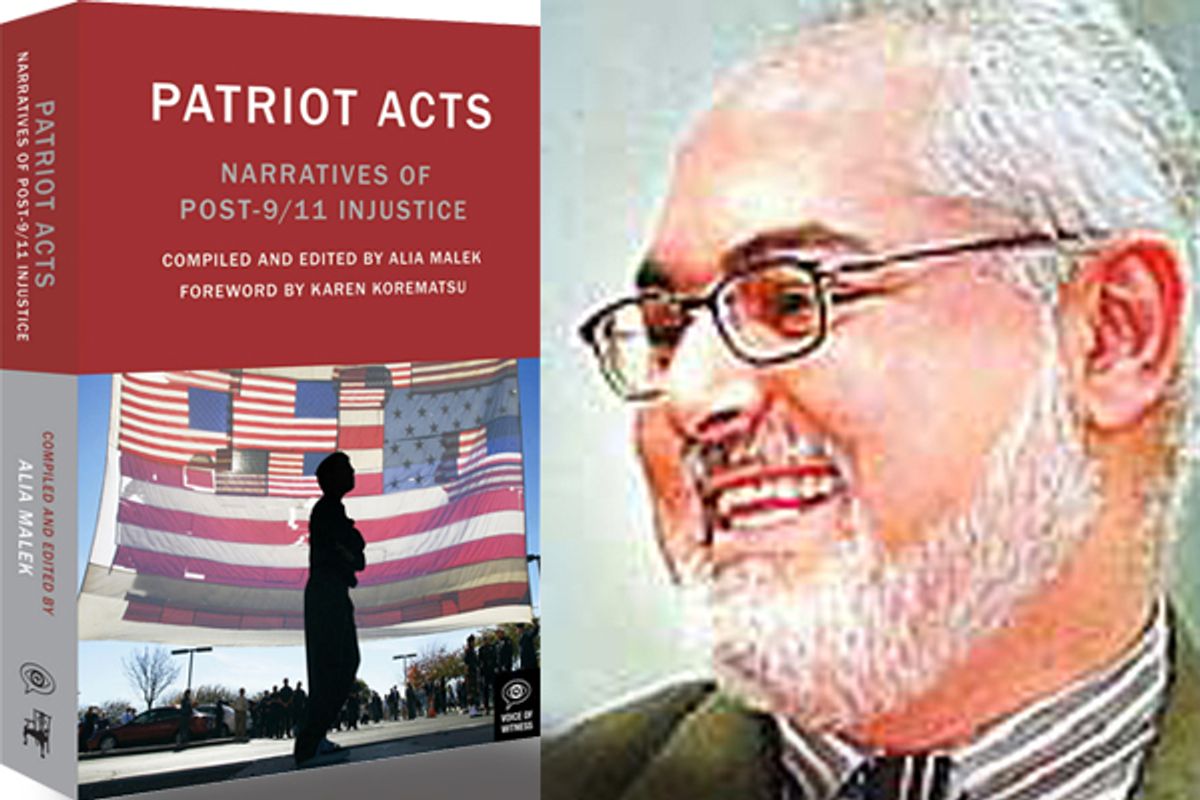

Every day through Sept. 11, we'll offer a new story from "Patriot Acts: Narratives of Post-9/11 Injustice," about men and women caught in the war on terror's crossfire.

Sara Jayyousi, now 15, was just 9 years old when her father, Kifah, was arrested in March 2005 and charged with providing material support to terrorists and with conspiracy to murder, kidnap and maim in a foreign country. The charges against him were the result of charitable contributions he made to an organization in Bosnia in the 1990s. Prior to his arrest, Kifah had been chief facilities director for the Washington, D.C., public school system, and then an adjunct professor at Wayne State University. He had also served in the U.S. Navy. When he was convicted in 2007, the judge noted for the record that there was no evidence linking Sara’s dad to specific acts of violence anywhere. The judge also said that he was “the kind of neighbor that people would want in a community.” In June 2008, Kifah was transferred to the federal Communications Management Unit (CMU) in Terre Haute, Ind.

On August 17, 2007, my dad and mom were going to court on the last day of the trial. That was the day the verdict was to be delivered. "High School Musical" was playing on the Disney Channel, and my sisters and I had never seen it before, so we were super-excited to watch it. We made popcorn and got situated around the TV. As my father and mother were getting ready to leave, my dad told us to come hug him before he left. He was holding his brown leather briefcase. He has had it as long as I can remember. He took it with him every day of the trial.

So I walked up and gave him a hug really fast and pulled away. I wanted to hurry back to the TV because "High School Musical" was starting in a couple of minutes! I didn’t know that was the last hug I was going to give him for a very long time.

My parents told us they would both be back in three hours. They had that much hope that my dad would be found innocent.

Four hours passed with me and my sisters watching "High School Musical," playing on the computer and messing around. Then we all started to get worried, and we didn’t want to be alone. So we called my mom’s friend, and she picked us up and took us to her house, where we swam in her pool. We just left a message on my mom’s cell phone telling her where we were going. We swam for two hours with my mom’s friend’s kids.

I was carefree and super-happy; it would be the last time I felt that way.

Suddenly, my mother appeared on the patio outside, next to the pool. Her face was red and puffy. I was freaking out because my dad wasn’t beside her, and she was holding his briefcase in her hands.

She sat us all down when we got out of the pool. She said our dad had been found guilty.

I burst out crying. She said he wasn’t going to come back. And I knew, from her holding his briefcase, that he really wasn’t coming back.

Before she told us all this, it had felt so hot. But then suddenly I got cold. I was shivering, a lot. I was in my wet bathing suit; it felt like snow.

Then I felt this pumping in my head. Everything was weird, it was all going wrong. I felt like my family had been put on pause, like everything else was moving, except us. I’d never felt that kind of pain in my life before.

I remember going back in the pool because I didn’t want anyone to see me crying. I remember my big sister came after me, hugging me. I cried a lot that day, more than I have ever done.

When we got home, my dad’s clothes were still were where he had left them in his room. That made it even harder for me.

That night, I remember me and my little sister piled in with my mom, and we slept next to her. I’ve never seen my mom so sad before.

We still have my dad’s briefcase. It has his smell in it. A cologne that smells really sweet and manly at the same time.

Handprints on the glass

Sara’s father was sentenced to 12 years and eight months. He began serving his sentence in Florida. On June 18, 2008, he was transferred to the CMU in Terre Haute, Ind., and was then moved to the CMU in Marion, Ill.

After he was put in the CMU in Terre Haute, telephone calls were every Wednesday and Sunday for 15 minutes. The thing about telephone calls is that we share them with my grandparents, so we get every other Wednesday but every Sunday. When he was in Terre Haute, we would visit him whenever we had a break at school, so every few months, but we’ve only been to Marion once because it’s a lot farther to get to. We always have non-contact visits, with a heavy glass in between us.

I have not touched my father since December 2007. If I had known, I could have made that hug longer.

Now, when we travel to Terre Haute, I stay in the car most of the time because my mom and I get stared at a lot for wearing hijabs. Like when we enter Olive Garden, everyone turns around. I can just hear them talking and whispering. I imagine them saying, “Isn’t that a terrorist?” or “Oooo, look, it’s an Arab.”

I don’t know what they say exactly. I’m glad I don’t.

I just don’t feel safe. I hate stares. I hate angry people.

* * *

The CMU visits are horrible. The visitation room there is so, so small, and it’s hot and uncomfortable. It’s surrounded by Plexiglas, and we’re separated from my father by a Plexiglas wall in the middle of the room. We are all locked in. I wanna break that Plexiglas wall.

We have to use a black telephone to talk to my father through the glass. Running through the glass are all these wires. The wires reflect on the glass, so it’s checkered and I don’t get a clear view. I can’t even see my father’s full face.

I want to see his face clearly. I want to notice the littlest things, down to every little dimple or freckle, so I can keep it in my head and remember them until the next visit. In Florida, I got to hug and kiss my dad. I got to smell him and see him as he is, without a checkered pattern from a glass on his skin.

One time we asked if we could hug him on a holiday, and the guards said no, because they didn’t have enough security. It’s not like he’s gonna kill us or hurt us. I mean, we are his daughters. It hurts so much knowing that he’s right there but you can’t touch him at all, like he’s an animal, like he’s gonna hurt you.

When it’s over, you hear the guard’s keys rattling on the door. That sound hurts so bad. All you see at the end of our visits are the handprints on the glass.

From "Patriot Acts: Narratives of Post-9/11 Injustice," edited by Alia Malek and published by Voice of Witness. This oral history collection tells the stories of men and women who have been needlessly swept up in the war on terror. Narrators recount personal experiences of the post-9/11 backlash that have deeply altered their lives and communities. For more information on the book and to learn more about Voice of Witness visit www.voiceofwitness.org.

Shares