(UPDATED)

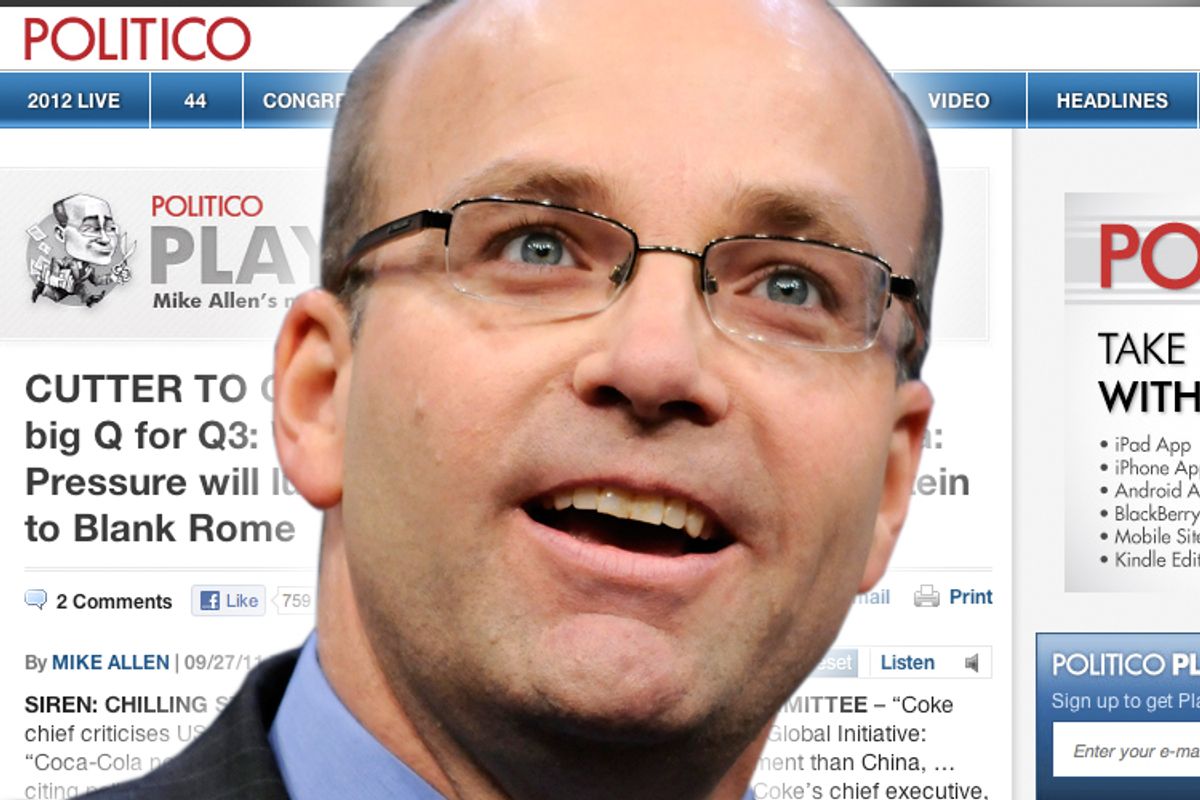

I actually have a soft spot for Playbook, the early morning political news round-up that Mike Allen writes for Politico. It's probably the most influential of the Beltway tip sheet genre, and it's generally an efficient way to learn what Washington is talking about at the start of each day.

But today's edition is just ridiculous. Allen leads with an extensive recap of an interview that Coca-Cola CEO Muhtar Kent gave to the Financial Times in which Kent contends that "in many respects" it's now easier for American companies to do business in China. He blames the "very large tax burden" on businesses in the U.S. and makes an argument that is commonly heard from wealthy executives these days:

However, Mr Kent said that US tax burdens and political polarisation were creating uncertainty for businesses and hurting investment.

“I believe the US owes itself to create a 21st century tax policy for individuals as well as businesses,” he said.

After presenting Kent's claims, Allen follows up with a commentary of his own under the heading "PLAYBOOK FACTS OF LIFE":

This is a massive wakeup call for official Washington, which keeps patting itself on the back for solving crises that shouldn’t be crises, while ignoring the crumbling of the system’s pillars. The Coke dude’s sentiments, which we hear CONSTANTLY and CONSISTENTLY from executives around the country, explain why an independent presidential candidate could have historic support, and why big money is panting after New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie. This certainly reflects the loss of business confidence in President Obama, which has occurred with startling finality. BUT WISE UP, GOP: These people don’t like or trust you, either, dawg. The story of the year ahead: Will/can anyone lead?

There are a few things worth addressing here. First of all -- "dawg"? If Allen was trying to make us think of Sean Connery in "Finding Forrester," maybe he succeeded. Otherwise, yikes.

But the real issue is his apparent willingness to accept at face value "the Coke dude's" gripes about tax policy -- and to instinctively frame Washington's inability to make him happy as some catastrophic bipartisan failure.

Complaints like Kent's are probably better addressed with a healthy dose of skepticism and critical thought. Let's face it, business executives almost always believe their taxes, whether corporate or personal, are too high. This is true whether the economy is weak or strong. I have no doubt that Allen hears complaints about corporate tax rates from executives all the time. But that doesn't automatically mean they're valid.

I'm reminded of the summer of 1993, when Bill Clinton pushed through a deficit-fighting plan that raised taxes on the top 1.8 percent of income earners. The country was just emerging from a painful recession, and business leaders screamed that Clinton was flirting with disaster. As Clinton's plan made its way through Congress, a survey from the National Federation of Independent Business found that small business owners' confidence in the economy was crashing -- a fact that congressional Republicans, who universally opposed Clinton's plan, made much of. But the plan passed anyway and it ended up having none of the horrific consequences that opponents had forecast.

When it comes to Kent's specific claims, it's probably worth keeping in mind that corporate taxes actually account for a fraction of the share of federal revenue and GDP that they comprised back in the 1950s. And while China may offer some inducements to business that the U.S. doesn't, there are trade-offs. As Kris Broughton explains:

The inhabitants of the executive suites in a lot of our U.S. corporations often display split personalities. One minute they are the CEO as warrior king, ready to brave whatever challenge may come, the next minute they are the CEO as Chicken Little, ready to proclaim that the sky is falling because our government has the gall to ask them to pay the cost of doing business in America.

Broughton also argues that:

Every CEO in the country needs to remove the word “uncertainty” from their vocabulary. It is a non-specific word that might mean anything, in the way that the word “discomfort” could describe the kind of pain you feel when you have a cramp in your leg or the kind of pain you feel when you have a broken neck. In CEO speak, “uncertainty” is a word that is usually delivered in an ominous tone when they are being interviewed, because we all know that CEO’s are being paid millions of dollars a year to assemble successful business strategies as simply and easily as kids snap together Legos.

The point here isn't that CEOs who say they or their companies are taxed too much should automatically be ignored. It's just that they shouldn't be afforded an exalted status in America's political debate. They have their own interests and their own blind spots, just like everyone else -- and that's the way they need to be treated.

Update: The Nation's George Zornick provides a thorough explanation of exactly what's going on here. Basically, Kent wants a tax break that will allow Coca-Cola to repatriate profits that it has parked in offshore tax havens (at a savings of hundreds of billions of dollars). Lest you think the repatriation of these profits will spur growth here, Zornick points out that a repatriation tax holiday in 2004 resulted in almost no new investment and that more than 90 percent of the money brought back ended up going to executives and shareholders. He concludes:

So, what Muhktar Kent is really saying: though his highly profitable company’s already-low federal tax rate is abetted by hiding profits overseas, he’d like to bring back those profits at an outrageously low rate so that his company can get even richer. Otherwise they'll keep the money in China, or Brazil, or wherever. That’s fine for Kent—it will certainly help his shareholders, which is his only true motivation. Just don’t tell Mike Allen.

Shares