“But all I could think about was Daddy”

–Alexandra Styron, “Reading My Father: A Memoir”

“Ocean’s Kingdom,” a ballet composed by Paul McCartney, with costumes by his daughter, fashion designer Stella McCartney, had its starry premiere in New York in late September, marking the first formal collaboration between a father and daughter who are famously close — and the happy antidote to what has otherwise been the year of Embittered Daughters of Famous Men.

In recent months, we have seen high-profile memoirs by the daughters of writers Joseph Heller and William Styron. Dubbed the “daughterati” by the New York Times, Alexandra Styron and Erica Heller both chronicled difficult, distant relationships with fathers so absorbed in their own careers and personal miseries they barely seem to notice their offspring. Jane Fonda’s latest self-help book, “Prime Time,” again revisits her famously prickly relationship with her aloof father — a relationship already explored at length in her 2005 memoir (and in Patricia Bosworth’s new Fonda biography as well).

But while all of these women have built successful lives in spite of their fathers’ varying degrees of emotional neglect, they can’t entirely seem to let them go, or even to stop engaging with them. These daughters seem less interested in revenge so much as comprehension: Why did I matter so little to him? They circle their subjects compulsively and the critical rigor of their analysis of their fathers’ weaknesses and failures feels even more intimate than a love song. They want to get close. Devoting a year, two years, even more to their fathers means extending a relationship that never satisfied.

What is it about these high-achieving daughters that seems to make them want to keep revisiting (through books, interviews, articles) their relationship with the man they feel has wounded or neglected them? There are many easy answers, such as financial rewards or attention, though none of these women — Fonda least of all — seem to be seeking either. The most oft-cited rationale (especially on book-jacket copy) is one we know so well from the pop psychology shelves: “closure.” But, as James Ellroy has said countless times about his own relationship with his mother, about whom he has written two books and several essays, “closure is bullshit.” By writing about them, talking about them, these daughters are able to continue the “dance with dad” another year, two years, even more, the book leading to book promotion, interviews, articles — more opportunities to extend the relationship indefinitely. When Fonda titles the chapter about working on the film “On Golden Pond” with her father “Closure,” you don’t believe her anymore than the speaker of Sylvia Plath’s “Daddy,” when she insists, in the closing line, “Daddy, daddy, you bastard, I’m through.”

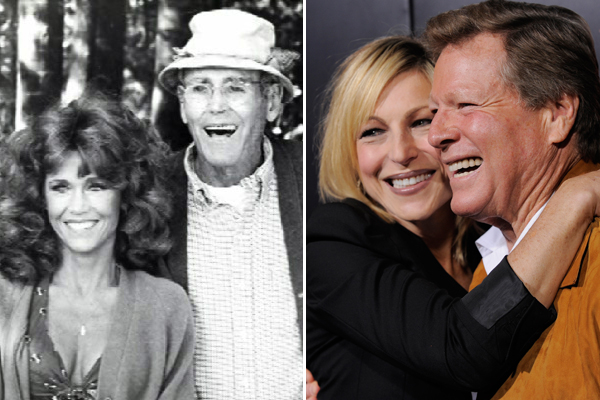

As is often the case, however, the most fascinating and extreme manifestation of this trend is its tabloid variation: the tormented relationship between Tatum and Ryan O’Neal. This summer marked the publication of Tatum O’Neal’s memoir, “Found: A Daughter’s Journey Home,” and the airing of an accompanying TV show on the OWN Network.

“Ryan & Tatum: The O’Neals” documents (or, more accurately, dramatizes) her attempts at reconciliation with her father, with whom she has been estranged for most of her life. From age six to 16, Tatum lived with her dashing movie-star father when her mother lost custody due to problems with speed, alcohol and boyfriends who liked to beat her children with fig-tree switches. After a decade of being her father’s partner in crime, however, Tatum watched her father “abandon” her for Farrah Fawcett, leaving his daugher to raise herself and her younger brother, Griffin. This abandonment — told, retold and told again in both of Tatum’s memoirs (this is her second) and the TV show and in countless interviews — is the Dominant Narrative of their relationship and, in some ways, Tatum’s life.

For women of a certain age, Tatum O’Neal was the “cool girl” ideal — sophisticated beyond her years, with her knowing turns in “Paper Moon,” “Bad News Bears” and “Little Darlings.” Now, we see her nearly 40 years later — blonde, beautiful and yet clearly broken — still playing the part of the desperate, attention-seeking little girl role with her father.

Their dynamic is perpetually pained and stoked regularly — even (or perhaps especially) during the media frenzy following Farrah Fawcett’s death. Few who heard the tale can forget it: Ryan hitting on Tatum after Fawcett’s funeral, not realizing, behind her sunglasses, it was his daughter. As he told Leslie Bennetts in Vanity Fair: “I had just put the casket in the hearse and I was watching it drive away when a beautiful blonde woman comes up and embraces me … I said to her, ‘You have a drink on you? You have a car?’ She said, ‘Daddy, it’s me — Tatum!'”

“That’s our relationship in a nutshell,” Tatum told Bennetts. “You make of it what you will.” Sighing, she added. “It had been a few years since we’d seen each other, and he was always a ladies’ man, a bon vivant.” It’s a complicated reaction to what one might expect to be a rather appalling Freudian moment. First, she asserts that her father’s seduction attempt was not an oddity but a fundamental feature of their relationship. Then, she tries to explain away the mistake. Finally, she points to his Don Juan qualities in a way that feels almost a sneaking celebration of him, and of herself for attracting his attentions.

You would not require this backstory, however, to find “The O’Neals” a dizzying, squirmy and occasionally deeply haunting experience, in particular the ways Tatum turns herself inside out for her father. Most of the time, she is the rueful daughter, still suffering and raging, while Ryan plays the befuddled helpless dad, seducing his daughter with attention and with sly attempts to get her to take care of him.

Unlike Styron, Heller and Fonda, Ryan O’Neal is the opposite of remote. Always ready to try to charm her and, more particularly the camera, he “gives” the most, always willing to stir up his daughter’s snarl of emotions and past grievances. He will feed his daughter’s rage and longing forever and still never give her exactly what she wants. The question is, what does she want?

The series’ most telling (and canny) scene is titled, on the OWN website, “He Said, She Said: Hot Tub Therapy.” As they lounge, Tatum speaks pensively of her desire to repair their relationship and Ryan dodges and dances his way through. It is a scene that recalls the famous father-daughter reconciliation scene between the Fondas in 1981’s “On Golden Pond,” daughter Jane, in exquisite aerobicized form in a bitty red bikini, trying desperately to connect with remote father, his eyes constantly drifting from her, refusing connection. Ryan O’Neal, however, gives Tatum everything Henry Fonda held back.

Then comes the inevitable moment when Tatum brings up, for what appears in the ten-thousandth time, her father’s desertion of her for Fawcett. Like a weary Spencer Tracy, Ryan insists, “You were not a kid. You were one of the most sophisticated 16-17 year olds I ever met.” Then he lets the hammer fall: “I know what I wanted,” he says to her, over the steam, over his own misty memories of Farrah. “I wanted her.” Quickly, Tatum, as if a wounded puppy, retreats, blaming their estrangement on his “temper.” His reply seems even more crushing. “It was the temper,” he concedes. “I fight with everybody, Tatum. Not just you. It’s nothing personal.”

Tatum stares at him a moment, then rests her head on ledge of hot tub, defeated. Because, of course, she desperately wants it to be personal. She wants to be just about her. She wants it to all have been about her.

One recalls Erica Heller recounting her horror over reading the gloomy portrayal of the protagonist’s daughter in her father’s autobiographical novel, “Something Happened.” When she confronted him, he replied, “What makes you think you’re interesting enough to write about?”

Ultimately, this string of daughter tales begs the question: what are we, the readers and viewers getting from it, other than a little schadenfreude over the difficulties these charmed girls have endured? How is it for women in particular seeing figures as accomplished as Alexandra Styron or Erica Heller still circling in that Freudian “remembering, repeating and (never quite) working through” dynamic, perpetually? One wonders how much of it might have to do with a possible curse of a generation (or two) of women who identified more with their fathers than their frequently career-less, unhappy or self-sacrificing mothers. Indeed, while women may not identify with their glamorous upbringings, those of us in the second or third wave of feminism may understand more than a little what it means to feel, all too strongly, the burdens associated with feeling, always, like one’s father’s daughter. After all, these are women who, to varying degrees, have followed not in their mother’s footsteps but their fathers.

Were they sons rather than daughters, we might immediately see these women as attempting, Oedipus-style, to overthrow their fathers, take his place. But instead we seem to be watching daughters trapped between identifying with their artist-fathers and sympathizing with their mistreated mothers with whom they cannot identify at all. But, perhaps most of all, they are stricken a terrible yearning. They want to, at least in part, be their father but also have his love as no one else has. There is a hunger in it that is desperate but also strangely moving. In her memoir, Jane Fonda cites a quote from psychologist Terrence Real, “Sons don’t want their fathers ‘balls’; they want their hearts.” “Daughters too,” Fonda adds — an addendum as rich in Freudian fervor as any you could hope for. In some ways, with these memoirs, they seek both.

Meanwhile, we might savor the seeming ease and contentment of the Paul and Stella McCartney relationship, which has led to “Ocean’s Kingdom,” the crown jewel of the New York City Ballet’s fall season. “I am a daughter working with her father, which is an incredibly remarkable experience in life no matter who your father is,” Stella told the Daily Mail. “It’s also quite an emotional thing.” After the premiere performance, she joined her father on stage to take a bow. “Ocean’s Kingdom” is, by the way, the story of a king and his daughter.

Megan Abbott is the Edgar award-winning author of four novels. Her latest, “The End of Everything” (Reagan Arthur Books), was published in July 2011.