The key to the U.S. government's case against two Iranian-born men charged Tuesday with plotting to assassinate the Saudi ambassador in Washington is an anonymous member of a Mexican drug cartel who has been charged with narcotic-related offenses and is currently on the payroll of the U.S. government.

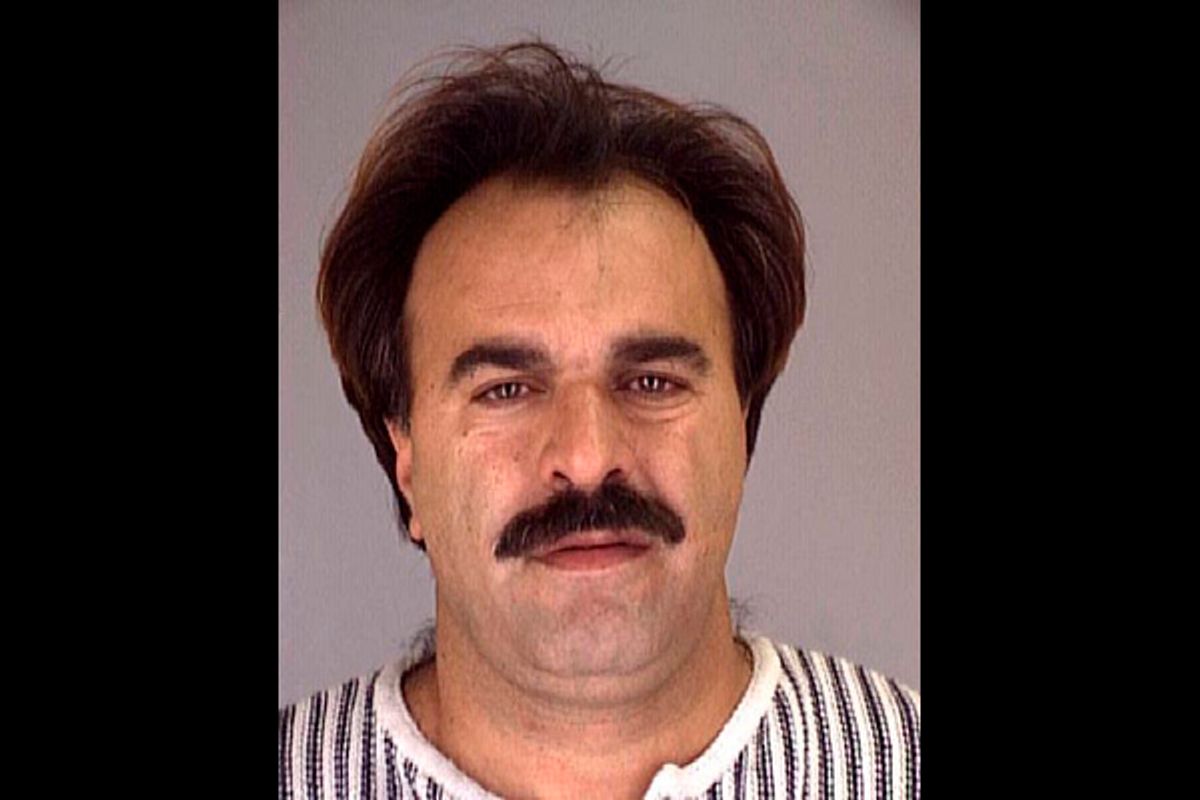

One anonymous source is not considered the basis of a credible news story but "CS-1," as he is identified in court papers, appears to be the linchpin to the U.S. government's five-count indictment of Mansoor Arbabsiar, a naturalized U.S. citizen, and Gholam Shakuri, allegedly an Iranian intelligence officer. The Obama administration has seized on the indictment to mobilize the U.S. government worldwide to a more confrontational stance against Tehran, something advocates of U.S. military action against Iran have long sought.

Within hours, the indictment revived talk of war betweeen the United States and Iran. The Wall Street Journal called the indictment "a sobering wake-up call" for those opposed to military action. The Iranian government called the charges a threat to "the peace and stability in the Persian Gulf region."

While the indictment has provoked skepticism among independent observers, and ridicule from Salon's Glenn Greenwald, the critical role of an anonymous informant in the government's case has drawn less attention. Virtually all of the overt acts alleged in the indictment took place in the presence of the informant or in response to his offer to carry out violent acts. His account of the alleged terror plot is driving U.S. foreign policy yet his veracity is far from established.

The informant's bona fides as a disinterested witness to criminal behavior are impossible to corroborate. According to the indictment, CS-1 was once charged in "connection with a narcotics offense" in an unnamed U.S. state, but those charges were dropped in return for his cooperation in various drug investigations. The informant has reportedly "provided reliable and independently corroborated information" leading to "numerous seizures" of narcotics, but no specific examples are given. A U.S. official who anonymously briefed selected journalists on the indictment on Wednesday did not offer any more details of the informant's past performance either.

The informant is said to be associated with an unnamed "large, sophisticated and violent" Mexican drug cartel, according to the indictment. ABC News reported that the informant presented himself as a member of the Zetas, one of Mexico's most notorious drug gangs. The indictment says he "posed" as a member of a cartel. But that doesn't mean that he was a member of the Zetas. He may be a member of another cartel who is just be a good actor. In any case, the informant is dependent on U.S. government officials for safety and money.

While the indictment says that CS-1 is a DEA informant, a footnote explains that he has been paid "by federal law enforcement officials" for his work. Given the CIA's escalating involvement in the Mexican drug war, the possibility that the informant works for the Agency should not be ruled out. As the New York Times reported this summer, "the United States has trained nearly 4,500 new federal police agents and assisted in conducting wiretaps, running informants and interrogating suspects." [emphasis added]

The U.S. team working with the Mexican counterdrug officials is based at the Pentagon's Northern Command (in an undisclosed location), so the secretive U.S. counterdrug policy in Mexico must be viewed as part of U.S. military posture worldwide. The possible role of the CIA and the Pentagon in cultivating cartel informants is obviously relevant to an indictment that has mobilized the U.S. government worldwide to a more confrontational stance against Tehran, something advocates of U.S. military action against Iran in both agencies have long sought.

Yet the government's sensational charges depend largely on one unknown informant's credibility, a situation reminiscent of the run-up to the invasion of Iraq. Then the uncorroborated claims of one anonymous source, known as "Curveball," proved to be influential in justifying war. They were also completely fabricated.

Curveball's allegations were used by the Bush White House to drive policy toward Iraq, just as the Arbabsiar indictment is being used by the Obama White House to drive Iran policy. Curveball claimed he had worked on Iraq's weapons of mass destruction program; the indictment says Arbabsiar and Shakuri sought to obtain "weapons of mass destruction" to carry out the assassination. One disillusioned CIA official later described Curveball as "a guy trying to get his green card" -- which might be CS-1's goal too, if there is any truth to his reputation ratting out legendarily vicious Mexican drug traffickers.

Whether CS-1 is a Mexican Curveball remains to be seen. CS-1's credibility will be tested when Arbabsiar is brought to trial and prosecutors will have to disclose much more of their evidence. (Shakuri is believed to be in Iran and is unlikely to see the inside of a U.S. courtroom.)

But the indictment indicates the government may have difficulty corroborating at least some of CS-1's claims. For example, Arbabsiar initially told CS-1 that he was interested in talking C-4 explosives, according to one passage in the indictment. Another passage says that after his arrest Arbabsiar waived his Miranda rights and immediately confessed. Arbabsiar reportedly said he had approached CS-1 with the idea of kidnapping the Saudi ambassador. Leave aside whether a man serious about organizing a political assassination in Washington would immediately tell the U.S. government about his plans. The contradiction in the indictment remains: Did Arbabsiar concoct a kidnapping plot or a bombing scheme?

The first several meetings between the two men were not recorded, according to the indictment. U.S. officials had to rely on CS-1's account of the meetings, suggesting that Washington has no independent means of confirming how the relationship between CS-1 and Arrabsiar developed.

The informant did arrange an audio recording of a meeting on July 14, 2011. According to the FBI agent who signed the indictment, "a draft transcript" of the meeting shows that the informant helped Arbabsiar develop the alleged plan telling him he would need "at least four guys" to carry out a bombing of a Washington restaurant where the Saudi ambassador was known to eat.

If that happened it would be a first, says Eric Olson, a specialist in Mexican security affairs at the Woodrow Wilson Center.

"I know of no case where the cartels have worked with any terrorist or foreign organization to carry out attacks in the United States," Olson said in a telephone interview. Olson said it was not even clear what the informant's relationship to the cartel was.

"Remember the Zetas are not organized as a military organization the way the Iranians are," Olson said. "They are much more diffuse."

In short, the Iranian terror case is an improbable story based on a unknown source that is shaping U.S. policy. Writing in the Huffington Post, Reza Marashi and Trita Parsi of the National Iranian American Council said:

Hawks in Washington will use these new allegations to support their preconceived notions on why defusing the Iran crisis cannot be done -- the timing isn't right; we need to garner more leverage by escalating the pressure; this regime needs enmity with America for its survival and so forth. Ironically, their counterparts in Tehran will echo similar sentiments.

And yet no one outside of the U.S. government knows if the source at the heart of the story is talking straight or throwing a curveball.

Shares