“When people say there is too much violence in my books, what they are really saying is that is there is too much reality in life.” --Joyce Carol Oates

The argument about whether young-adult fiction has become too adult in its subject matter is a long-standing one. My concern is not this debate -- in fact, I consider it to be moot. The YA category is a marketing distinction, not a moral one, however much parents would like it to be a synonym for “safe.”

But you are raising a child, possibly the least safe enterprise imaginable. And if this child is also a reader, there is a high probability that, closely preceding adolescence, his or her literary curiosity will hit an exponential curve -- one that will be made apparent in a taste for books intended for the adult market. Let’s call this the V.C. Andrews Curve, after the author of "Flowers in the Attic." It can be attributed more or less to two phenomena: first, with a simple increase in reading comprehension, adult genre fiction will be of considerable appeal owing to the accessibility of the prose and story lines. Second, irrespective of age, human beings have an innate attraction to the dramatization of issues around life’s central mysteries: its genesis and termination. Put another way, not only will your kids survive an exposure to violence and sexuality in books, but it is crucial to their moral development.

So the VCA Curve should not be resisted. It should be shouted from the rooftops: Your child is a human being! A cool one! Because this human being is building an infrastructure for critical reasoning in a frequently bizarre, paradoxical universe where fairly miraculous and fucked-up stuff happens on a regular basis. Of course adolescents have an irresistible attraction to adult themes; perverse and puritanical an instinct as there is in this culture to prolong childhood, there is a far stronger counter-instinct in children to analyze, simulate, and as soon as humanly possible participate in the challenges of adulthood. This is not to suggest that growing up is a process that should be unnaturally accelerated, or that it can be in the first place. These days, casual observation suggests that in a modern urban environment, childhood is a stage that lasts approximately 30 years. But we should be counted lucky when this fascination with the adult world manifests in wanting to read more books.

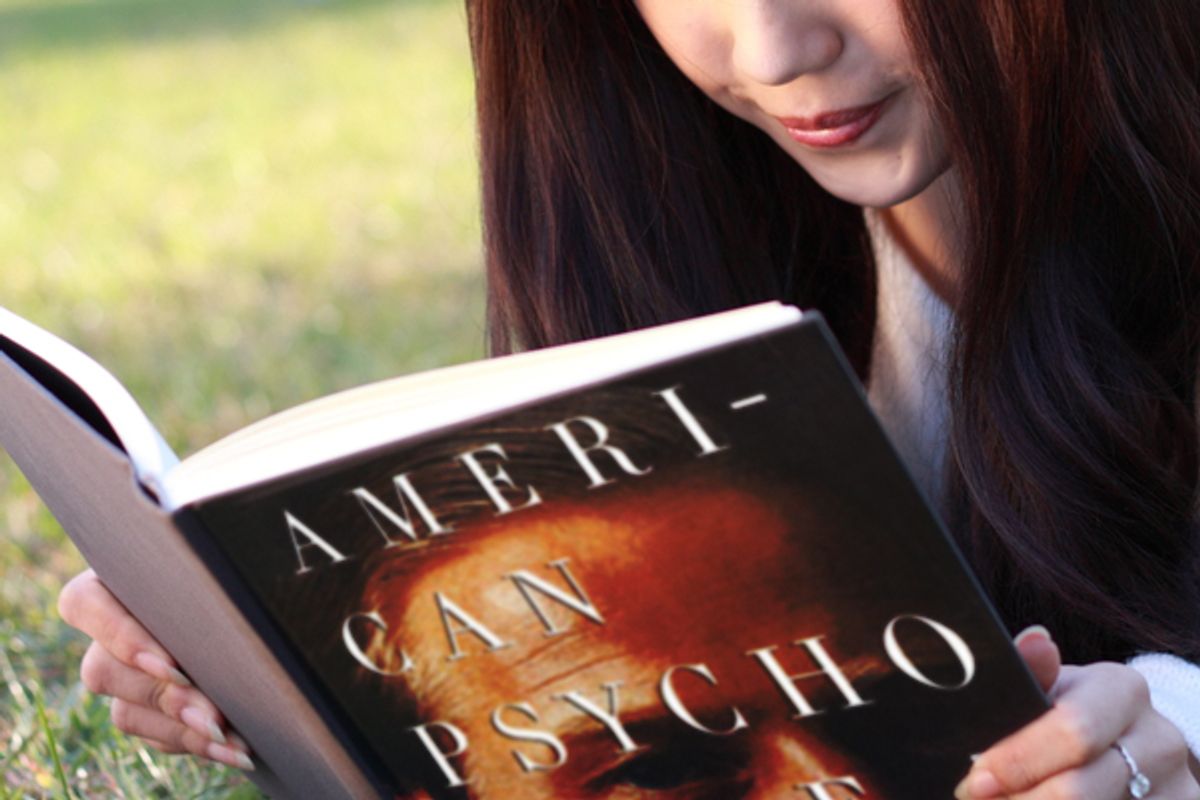

A personal example: During my own wayward, Rust Belt Pennsylvania adolescence, the movie "American Psycho" was a great hit among my friends. Its protagonist, Patrick Bateman, blood-drenched, chainsaw wielding, and wearing nothing but sneakers and a smile, was an avatar of the mindlessly, ecstatically destructive impulses that comprise no small part of the average teenage male’s psyche. He was the kind of guy we wanted to be around. Then I read Bret Easton Ellis' book. “Ecstatic” is not how I would describe that experience. Because reading is the antithesis of desensitization, and to actually accompany this character for 400 pages of appalling, despicable acts – as well as his stunningly annoying and tedious class obsession -- was so unpleasant that even the sight of the book, to this day, induces a physically ill sensation best described as a moral hangover. This was a guy I wanted nothing to do with, but more importantly, wanted to be nothing like. Within the virtual reality of the text, I came to an independent moral conclusion that he really, really sucked.

Not that this is intended to veer into some half-baked indictment of sensationalistic films or video games. For one thing, a large segment of my generation spent our formative years upper-cutting opponents into moats of acid in Mortal Kombat. The singular reward of watching their gleaming skeletons surface will always fill us with a childlike sense of satisfaction rarely paralleled in the adult sphere: The obverse of the instinct to protect children from the bigger and messier reality of adulthood is the inability of most adults to experience the mere joy of children. (Why adults should read children’s fiction is its own issue.) But film’s most essential function is sensorimotor stimulation; like pop music, it is obligated first to induce emotion, and only second -- distantly second -- to provide the first clue of how you got there. What neither films nor video games are cut out for is developing the critical faculties that reading does. Higher-order mental processes are not even strictly required to enjoy a movie, whereas books, by nature, are undemocratic. A combination of education and innate sensitivity is required to enjoy them, and the reward is the closest possible experience to entering another human being’s consciousness and revising the parameters of your own. It’s harder because it should be.

Returning to my own adolescence: A few years younger than me in school was a student that I would have seen around in the halls, but did not meet, to my knowledge. At the age of 15, he murdered his adoptive mother and was pulled over in a truck full of guns. Evidently he had plans for a Columbine-style shooting spree. This boy, of course, had a history of emotional problems and was known to be the victim of bullying. Critical reasoning plus common sense leads to context. And the complexity and shifting nuances of life are far more easily navigated with the three-dimensional psychic cartography generously provided by writers who have thought about this stuff before you. When this incident occurred (or, failed to) the magnitude of it was difficult to process – and remains to be; even imagination has its limits. But at the same time, thanks to the VCA Curve, I had no difficulty identifying, and more importantly having compassion for, the motivations at work. I had read "Carrie."

Empathy is not an exclusively human faculty, but we are the only known species that can consciously get better at it. Curiosity is also not ours alone, but only we can transmit what we have learned to others of our kind in the aesthetically gratifying vehicle of narrative without needing to be physically present, or even alive. This is a terribly wonderful thing — but it is not safe.

It’s hard to think of a more intimate and transmuting experience than the first time you are scarily aroused by something you’ve read; it’s a loss of virginity with more complete implications than the hapless and self-conscious mechanics of the physical initiation. Or another first: when you realize the inevitable fact of your own death. For me, this milestone occurred reading "Jurassic Park" at 10 years old, when the Dilophosaurus eviscerates Dennis Nedry. This was, with justification, one of my favorite scenes in the movie. But it was not until reading the same incident from the character’s point of view, and going black -- then moving onto the next chapter and never returning to Dennis again because there was nothing but that ineffable, inescapable blackness -- that it clicked that this was a thing that could, and one day would, happen to me.

Maybe that’s the heart of the matter. Your child is going to die one day, the same as you. This is the single worst piece of information a member of our species can possess, and in a moment of empathy inculcated in no small part by his literary freedom growing up, the author sincerely apologizes to his mother for how bad he is at sending confirmation text messages that he has survived routine air travel. But in spite of the pain this knowledge necessarily causes parents, the child can handle it. They're equipped with a strength and ingenuity they're not often enough credited with. Life’s genesis and termination -- and every gradation of human experience in between -- is their birthright. They are entitled to learn about it at exactly the rate it is appropriate to their individual moral development to do so. And as long as you love them enough, they’ll end up basically OK.

Shares