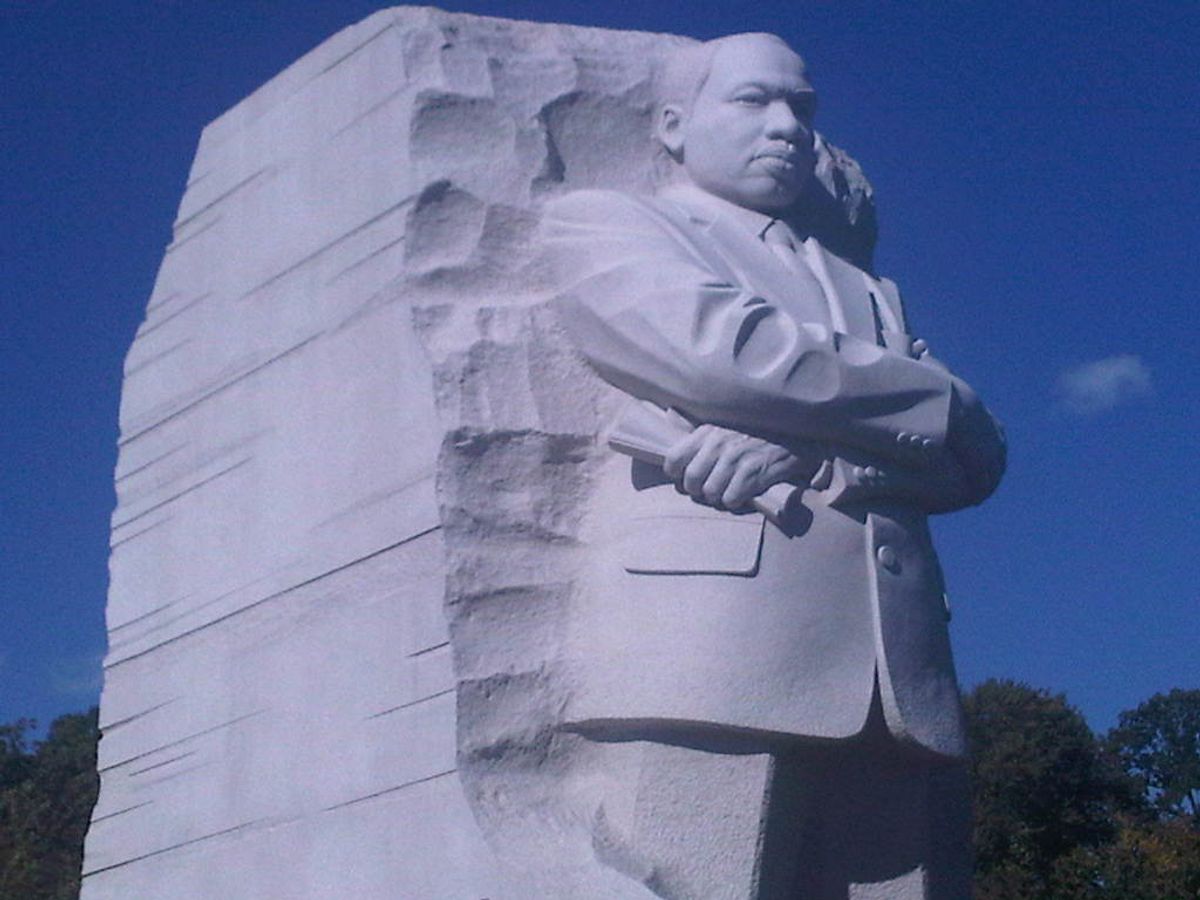

There is only one statue of Martin Luther King Jr. at the memorial site in Washington DC dedicated Sunday by President Obama in front of a crowd of thousands. But two faces of King were on display in the morning ceremony: King the all-American motivational speaker; and King the radical agitator. The latter was clearly the crowd's favorite but the president embraced the former, thus highlighting the question that dominated the weekend in Washington: What does King mean to American politics today?

Twenty four hours earlier thousands of people had rallied to the memory of the radical King by marching to the site of 55-ton bust of the civil rights leader on the National Mall. The crowd was fed by hundreds of protesters from the two occupation movements now occupying McPherson Square and Freedom Plaza in downtown Washington. They first marched on the offices of Bank of America before heading to the King memorial where they were swallowed up by thousands of protesters on a "march for jobs and justice," sponsored by by labor unions and the National Action Network of MSNBC talk show host Al Sharpton.

Not long after Obama finished speaking on Sunday, Princeton professor Cornel West and 13 other people from the Occupy Washington movement were arrested on Capitol Hill for demonstrating too boisterously against the Citizens United decision at the U.S. Supreme Court building.

For the protesters in Washington, King's memory calls for militant confrontation in the service of radical change.

"He would be right here with us," retiree Sarah Touton said at the McPherson Square occupation, two blocks north of the White House. "There's no doubt he would be with the 99 percent."

"He would say we need to stop this Tea Party movement that is pitting Americans against Americans," Dr. Linda Evans, professor at the Community College of Philadelphia told me on plaza surround the King statue. "We all have something in common to unite us." Evans, who came with a busload of members of the American Federation for Teachers, welcomed the occupation movement as "long overdue."

But as the crowd gathered at the memorial site on Sunday morning, politics gave way to History. King was taking his place in the American pantheon, an unlikely development for a clergyman who never held public office but an affirming occasion for a nation that prides itself on self-invention. Confrontational esprit gave way to patriotic pride.

The setting itself embodied America's penchant for inventing the past. When the national capital was established here in 1800, slavery was legal and the King memorial site was part of a vast pestilential bog. The tidal swamp of the Potomac River was only slowly filled in and landscaped over the course of two centuries. The mud of history became the foundation for marble monuments.

Now the King statue is installed in the Mall's constellation of national symbols, located halfway between the Jefferson Memorial and the Lincoln and Vietnam War memorials. King's visage glares across the Tidal Basin at the temple of Jefferson, slave owner and empire builder, who embodied all of the contradictions against which King struggled. The back of the King statue is turned on the nearby Vietnam War memorial, which honors those killed in an imperial adventure that King opposed with a fervor some of his latter-day admirers prefer to forget.

In this setting, it was unsurprising that King's daughter Bernice gave a fiery speech calling on the the country to live up to her father's ideals. Declaring Americans should never adjust themselves to 1 percent of the people controlling 40 percent of the nation's wealth, she called the worldwide occupation movement an "explosion of freedom" that her father would have welcomed. (She added that her father would have urged the protestors "to conduct ourselves on a higher plane of dignity and discipline.")

Jesse Jackson lamented the celebration of King's legacy came at "a "sad time" with widespread unemployment, Congress in rebellion against the idea of helping the jobless, and the first African-American president facing unprecedented "retribution, retaliation, and venom." Jackson described King's famous 1963 March on Washington as an occupation, and called the young people leading today's movement "the heirs of Dr. King."

"He didn't give his life for a statue," said Georgia congressman John Lewis to applause. "He gave his life for the least among us."

But while no one could doubt the still-spry 90-year old Joseph Lowery when he declared that King is now installed as "a founding father of the new America," the extended speaker's program also illuminated how the beatification of King can serve to muffle his message.

Tommy Hilfiger took the podium to remind the crowd that King provided "inspiration" for his foundation to do good deeds. Diahann Carroll, star of a television show only Google can recall, spoke of her own very significant encounters with Dr. King which had "inspired" her. The chairman of General Motors said King had "inspired the GM family." In this comforting perspective, King is welcomed as a motivational speaker just slightly ahead of his time, not as an agitator against the existing economic order.

As the restless crowd chanted "Four more years," Obama finally took the stage to sustained cheering. In his 20-minute address the president split the difference between King the radical and King the inspirational speaker by portraying the civil rights leader as a long-suffering and underappreciated agent of change.

King, he said, is known to schoolchildren for his 1963 speech for "prophesizing of the day when our jangling discord of our nation would transformed into the beautiful symphony of brotherhood." With that happy day still distant a half century later, Obama said "let us remember that change has never been quick. Change has never been simple or without controversy."

The president noted that King was not considered a unifying figure when he was alive, a fate that Obama seems to share. Obama did not sugar coat the state of the nation with an unemotional mention of "rising inequality and stagnant wages." Nor did he recommend King's militancy to the crowd or the nation. He recommended his tolerance.

"He calls on us to stand in the other person's shoes, to see through their eyes and to understand their pain," he said. By this he meant the person whose child goes to a good school should sympathize with the person whose kids goes to a school that is decrepit. Obama's unobjectionable formulation merely omits what the marchers of the day before had emphasized: King's critique of the militarized U.S. economy that generates systematic inequality and the moral imperative to do something about it.

Obama alluded to the occupation movement but without mentioning the O-word. "Aligning our reality with our ideals often requires the speaking of uncomfortable truths and the creative tension of non-violent protests," he said, rather drily. He allowed that King's example showed that "those with power and privilege will often decry any call for change as divisive," but added "any social movement has to channel this tension through the spirit of love and mutuality."

In this view, King resembles no one such much as Obama himself: a misunderstood all-American idealist who is unfairly maligned as a radical.

"His life story tells that change can come if you don't give up," Obama concluded. That won't quite fit on a bumper sticker but it amounts to the president's 2012 reelection slogan. For this mostly African-American crowd, proud of their favorite son and impressed by his dignity in the face of a cynical Republican onslaught, that summation may have been anti-climactic but it was sufficient.

Obama is still seen as more victim than villain by those most disturbed by the rise of the 1 percent and dispossession of the 99 percent. I saw a couple of "Arrest Bush and Obama" tee-shirts at the occupation encampments. In the crowd at the memorial dedication I saw many more that pictured King and Obama with the inscription, "Dreams do come true." To the core constituency for change in America, Obama can deploy King's memory however he wants. If the president won't bring the radical King into America's politics today, the likes of Cornel West and the occupation movement will have to do it for him.

Obama exited to applause that was as mild as it was brief The crowd was filing toward the gates when Stevie Wonder took the stage and the band struck up his cheeful ode to King, "Happy Birthday." For the first time all day, people started singing along.

Shares