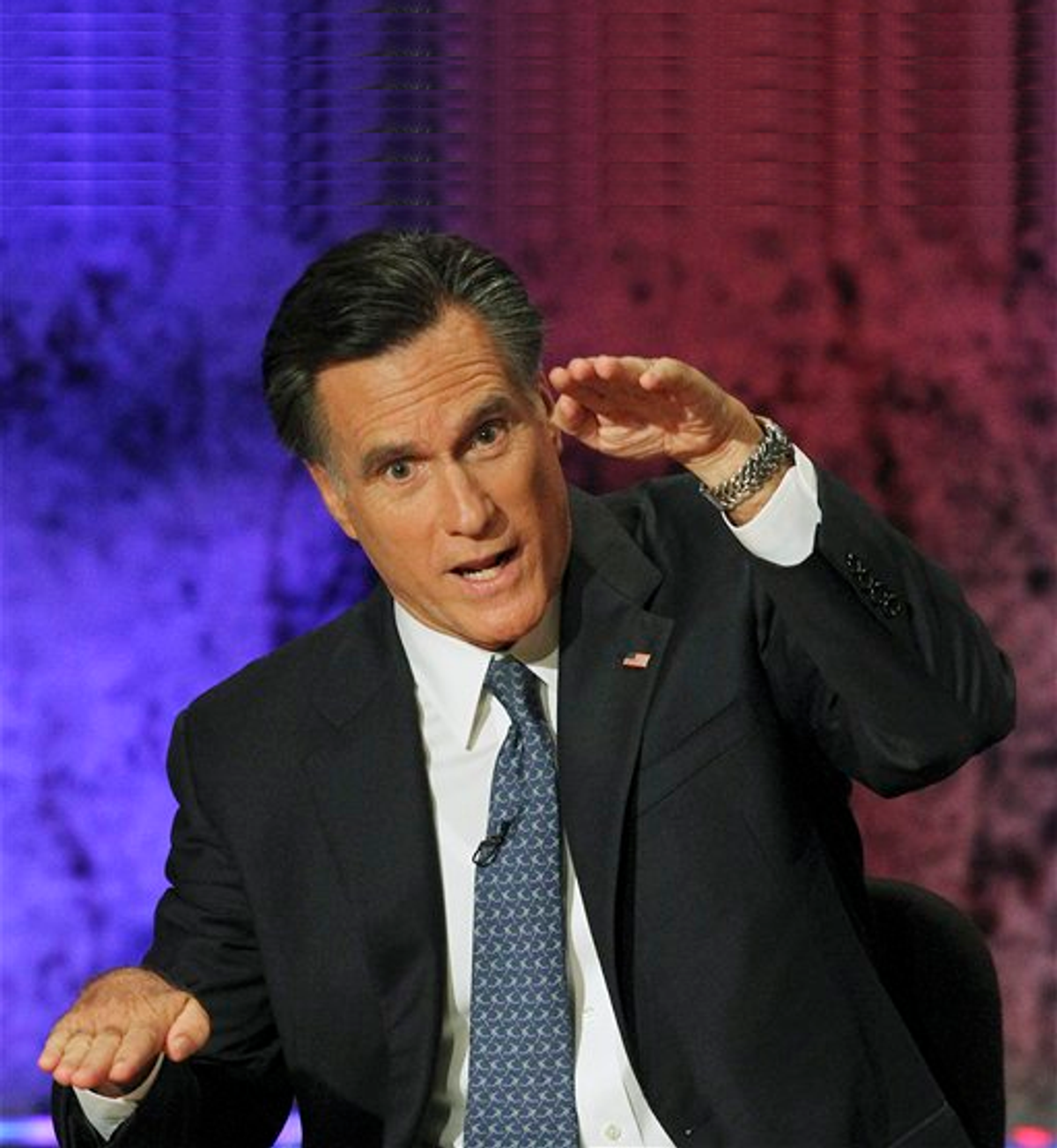

In an appearance on CNN on Sunday, Newt Gingrich faulted the "establishment media" for failing to understand Mitt's Romney's "huge problem":

He's a very likable person. He works very hard. He's very smart. And he is a Massachusetts moderate Republican. It is the Nelson Rockefeller problem. I mean, there is a natural ceiling.

This is not actually an original observation. Others have drawn parallels between Romney's current effort and Rockefeller's failed bid for the GOP nomination in 1964, when he lost out to Barry Goldwater, and there's plenty of superficial appeal to this thinking: Two men from the Northeast, each with a gubernatorial background, each personally wealthy, and both widely perceived as moderates. And there is a chance that Gingrich will ultimately be proven correct, that this perception will make it impossible for Romney to win over the GOP's Tea Party base and capture the nomination.

Nonetheless, it should be emphasized: Comparisons between the 2012 and 1964 GOP races completely miss the mark, and treating the current contest as a repeat of Goldwater vs. Rockefeller is a poor way to understand the evolution of the Republican Party since the 1960s and how Romney fits into it today.

The most important thing to realize about the Nelson Rockefeller who ran for president in 1964 is that he was an authentic political liberal, a believer in the power of government to fix the nation's biggest problems, and he made essentially no effort to hide it. He favored strong civil rights laws, expansive anti-poverty programs, and major investments in education, healthcare and conservation. And the most important thing to realize about the Republican Party of 1964 is that to many of its leaders and rank-and-file members there was nothing at all alarming about Rockefeller's liberalism. It was common in a party that was littered with Northeast moderates and liberals and light on conservative white southerners.

There was a burgeoning conservative movement in the party, though, and it rallied around Goldwater, a second-term Arizona senator (and the only non-Southern Republican to join the unsuccessful Senate filibuster of that year's Civil Rights Act). Believing the numbers were on his side, Rockefeller openly attacked the Goldwater faction and its "extremism" and made little effort to modulate his own liberal rhetoric. That he ended up losing didn't necessarily mean that Rockefeller's calculation was wrong. His own scandalous divorce and the Goldwater camp's shrewd understanding and manipulation of the delegate selection process were probably the two biggest factors in the outcome. (The coast-to-coast primary campaigns that we are now familiar with didn't exist in '64, when only a handful of state contests were contested.)

The Goldwater-Rockefeller race, in other words, represented a clash of seriously conflicting ideologies, with each man promising to lead the party in a fundamentally different direction. In victory, Goldwater crafted the most conservative platform the Republican Party had ever seen; had Rockefeller prevailed, that document would have looked far different. This is nothing like the situation today. The great ideological battle within the Republican Party is over (and it has been for a while), with Goldwater-style conservatism prevailing -- and with Tea Party absolutism taking hold in the Obama era. The party's convention next summer will be filled with very conservative delegates who will approve a very conservative platform no matter which candidate emerges from the primaries. And if that candidate is elected president, he or she would be risking a debilitating intraparty mutiny by straying too far from the platform.

This is why the Romney-as-Rockefeller comparisons aren't very helpful. Romney just isn't running the kind of campaign that Rockefeller ran. Ever since he decided to give up on winning elections in Massachusetts and pursue the presidency, Romney has been tailoring his positions and rhetoric to the very conservative base of the national GOP, throwing out his old beliefs if need be. Rockefeller happily picked fights with the right, but Romney has been doing everything he can to make conservatives believe he's just like them. If he wins the nomination, Romney will presumably affirm a platform that calls for repealing healthcare reform, outlawing abortion, protecting "traditional marriage," extending the Bush tax cuts in perpetuity, undoing the Dodd-Frank Wall Street reforms, radically curbing the EPA's power, and opposing the "class warfare" agenda of Democrat -- just as all of his opponents would.

So why is Romney frequently portrayed as a moderate? There are three reasons. The first is that he absolutely was a moderate -- or at least presented himself as one -- in his Massachusetts days. The second is that it's in the interest of his opponents, like Gingrich, to claim that he still is one. And the third is that he's adopted a more restrained style in this campaign; four years ago, Romney missed no opportunity to toss red meat at the base, but this time he's played the role of November-minded front-runner and held back.

The key, though, is that he's shown almost no interest in antagonizing the GOP base's Tea Party sensibilities. About the closest he's come is on healthcare with his refusal to claim that his own Massachusetts law was a mistake and to beg forgiveness for it. But it's easier to read this as a practical consideration than a Rockefeller-like stand of ideological defiance: Suddenly claiming that his biggest single achievement in Massachusetts (one that he bragged about as recently as 2008) was one giant mistake would make his image as a flip-flopper much worse and carry potentially serious general election consequences. Short of saying he was wrong, though, Romney is doing everything else imaginable to convince the Tea Party right that he's as committed to dismantling ObamaCare and doing nothing to replace it as they are.

And if you put healthcare aside, there really aren't any big spots where post-Massachusetts Mitt is out of step with his party -- which explains why Rush Limbaugh felt comfortable pronouncing Romney the embodiment of "all three legs of the conservative stool" just three years ago.

The comparisons to 1964 just don't compute. Back then, Republicans were asked to choose between two completely different directions for their party. But today, the direction is already set. The GOP is a deeply conservative party that will nominate a candidate for president who publicly commits himself or herself to a deeply conservative agenda. This isn't to diminish Romney's problems within the party; there is clearly a strong sense among conservatives that he secretly clings to moderate beliefs and that he'd betray them as president. But a different parallel is probably more apt: It's not so much Nelson Rockefeller from 1964 whom Romney is channeling; it's George H.W. Bush from 1988.

* * *

I was on MSNBC's "Hardball" Friday night with Matt Kibbe from FreedomWorks and talked about Romney's moderate reputation and his struggle to win over the GOP base:

Visit msnbc.com for breaking news, world news, and news about the economy

Shares