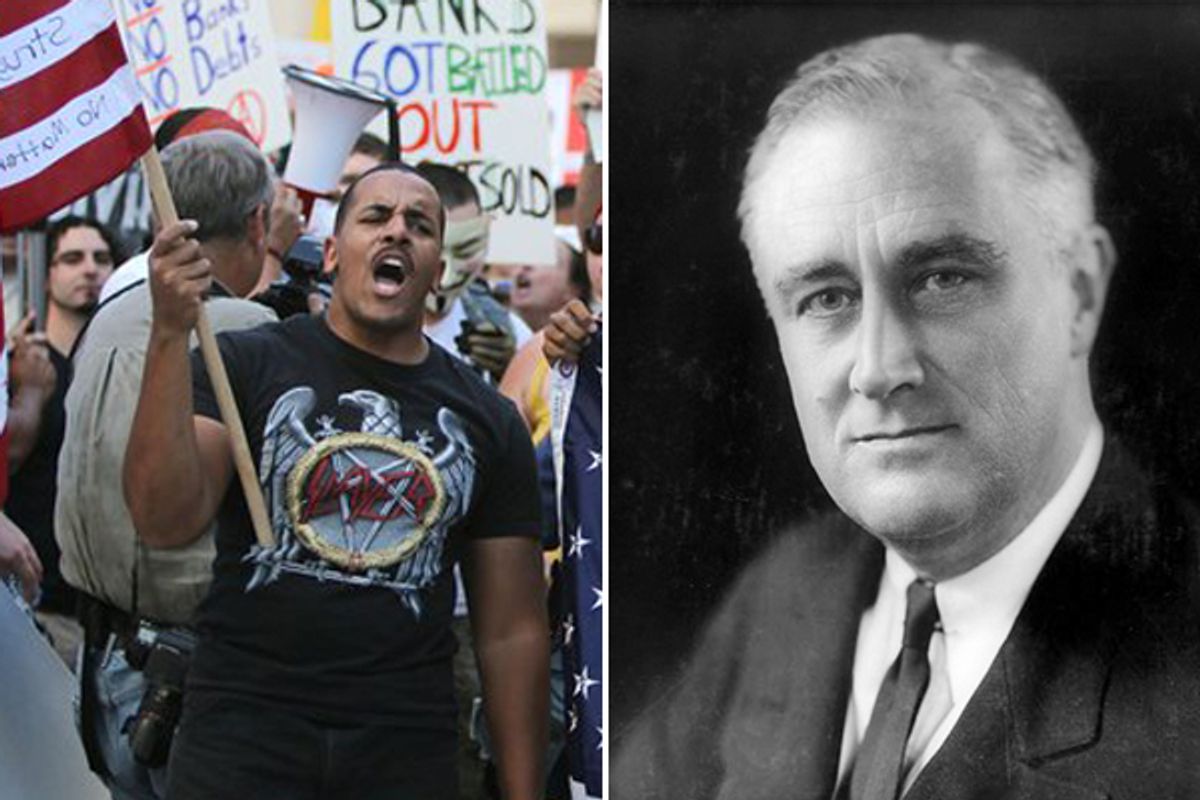

Will the worldwide “occupy” demonstrations make 2011 the new 1968?

The liberal left must hope not. The global wave of left-wing radicalism that peaked in 1968 was followed by a generation of right-wing reaction in the United States and Europe. The rise of counterculture frightened the “silent majority” in the U.S. and Europe into supporting politicians like Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher, who, running campaigns based largely on patriotism and traditional values and “law and order,” used their power to undermine the labor market regulations and social insurance programs that had protected the socially conservative working classes who voted for them.

It is all too easy to write a script for a post-Reaganite, neo-Nixonian conservatism that emphasizes law and order. If protesters in Wall Street and other downtowns go from waving placards to smashing windows, it would be easy for the right to win over the suburban majority by accusing the center-left of coddling law-breaking downtown protesters as well as law-breaking illegal immigrants. At the moment much of the public is favorably disposed toward the occupation protests, but attitudes may change if countercultural shantytowns grow up in urban parks and confrontations with police and local governments become common.

In the event of such confrontations, the upper middle class might identify with “the kids” — their underemployed, college-educated kids, camping out in the protest. But the white, brown and black working classes might have more sympathy with the other “kids” — the young, less well-educated police officers.

“Your parents had to have a lot of money, for you to take part in the Summer of Love,” a veteran of the hippie movement once told me. A generation ago, the point was not lost on the white working-class “hard hats” who turned against the Democratic Party when the children of privilege denounced their own relatives in military and police uniforms as pawns of an oppressive police state.

But there are other possibilities. Democratic strategists across the country are no doubt pondering how the somewhat unfocused demonstrators can be turned into a “Tea Party of the left” that can be deployed as reliable Democratic voters in future elections. Other members of the progressive establishment may try to co-opt this essentially anti-political movement into the elaborate structure of single-issue progressive patronage networks.

Maybe occupiers can be persuaded to join minorities, women, LGBTs and environmentalists as officially sanctioned progressive interest groups. Maybe in 10 years there will be foundation-funded Occupation programs, each with their own well-paid administrators, followed 20 years from now by endowed chairs in Occupation Studies, occupied by chubby, middle-aged veterans of Zuccotti Park.

There is a third, more promising possibility. Instead of provoking a conservative backlash, or being co-opted by the existing progressive identity-politics machine, the Occupy Wall Street movement could indirectly benefit the American center-left by re-creating an American radical left.

If left-radicalism is defined as anti-capitalism and pacifism, American progressives and liberals in the tradition of Woodrow Wilson and Theodore and Franklin Roosevelt and Lyndon Johnson have never been radicals. The goal of progressive-liberals has been to save American capitalism by reforming it, not to replace it. And the progressive-liberal presidents led the U.S. into the world wars and the Cold War, over the objections of the pacifist left and the isolationist right. Today a case can be made for considerable strategic retrenchment by the U.S., but progressives in the Rooseveltian tradition want the country to maintain the capability to intervene in conflicts beyond North America, if that is necessary to prevent hostile powers from dominating the populations and resources of key regions.

For most of the 20th century, the American center-left was attacked simultaneously by the radical left and the reactionary right. This allowed progressive-liberals to position themselves as the reasonable alternative to the extremes of socialism and plutocracy.

This explains the paradox that the end of the Cold War hurt the center-left in America and Europe by depriving it of a challenge from the far left. Although Western Marxists insisted that the “state capitalism” of communist regimes did not discredit true Marxism, in the event the collapse of the Marxist left, even in non-communist forms, quickly followed the demise of Marxist-Leninist regimes in the Soviet bloc and the repudiation of communist theory by nominally communist regimes in China and Vietnam. Today the only Marxists are found in academic literature departments.

What remained on the radical left, after the collapse of Marxism and other, more utopian versions of socialism, were identity politics and Malthusian gloom-and-doom environmentalism. Both of these were easily co-opted by the economically conservative neoliberals who took over former progressive parties in the Atlantic world like America’s Democrats and Britain’s Labour Party. It costs corporations and governments nothing to “celebrate diversity.” And financiers in Wall Street and the City of London figured out ways they could reap windfall profits from Green measures like cap-and-trade on greenhouse gas emissions, renewable energy mandates imposed on utility companies, and government subsidies to renewable energy start-ups.

Because there was no longer any significant economic radicalism after the Cold War, old-fashioned economic progressivism — the living wage, universal social insurance, equality of educational opportunity — became defined as “the radical left” in the 1990s and 2000s. Meanwhile, Reagan-Thatcher conservatism, which had been the right-most right during the 1970s and 1980s, was out-flanked by an even more extreme free market fundamentalism, symbolized by the Tea Party — a further right.

The appearance of the further right, and the disappearance of the far left, shifted the entire spectrum to the right for the last two decades. New Deal-style progressivism, once the center between Marxism and conservatism, became the left. Reagan-Thatcher conservatism, having been the right, became the new center; and a new, radical economic libertarian right, far more extreme than Reaganism and Thatcherism, became the new right.

American politicians like presidents and senators with large and diverse constituencies, if not members of Congress from homogeneous districts, prefer to be in the center. Being defined as centrist also helps raise money, because big money tends to be risk-averse and fears extremes. It was only to be expected, therefore, that in the post-Cold War era, successful Democratic presidential candidates like Clinton and Obama would campaign and govern as moderate Reaganites rather as Rooseveltian New Dealers. This explains why Obama and the congressional Democrats, seeking to be “centrist” in the transformed political landscape, rejected the New Deal approach of universal health insurance, in favor of an approach to healthcare reform inspired by Republican Gov. Mitt Romney in Massachusetts and the conservative Heritage Foundation.

The Occupy Wall Street movement has the potential to help the center-left, even if some of its activists despise the center-left the way that the New Left in the 1960s and 1970s dismissed progressive-liberals like the Kennedys and Johnson as sinister “corporate liberals” promoting the “warfare-welfare state.” The reemergence of a radical economic left can create a fourth point on the political spectrum, changing the relative position of all other points. The Tea Party right, now the mainstream right, would become the far right. Today’s center, shared by Clinton and Obama with Reagan and the Bushes, would become the new center-right. And the new center-left would be something like New Deal liberalism — to the left of Clinton and Obama, but to the right of an anti-capitalist left. Better yet, if the public tired of Tea Party conservatism, the far right could implode and the new “far right” would be moderate economic conservatism of the Reagan-Bush-Clinton-Obama variety. What until recently has been the left -- old-fashioned social democratic reformism in the New Deal tradition — might once again be the center.

Good cop, bad cop works in politics as well as in police interrogations on television. A reformist center-left benefits from having an angry radical partner that it must restrain. Whether it takes the form of the Occupy Wall Street movement or something else, a radical economic left that despises weak progressive reform can inadvertently strengthen the position of the reformist progressives.

Shares