More than six years after he started working on a movie about a font, director Gary Hustwit has now tackled the gargantuan topic of urban design. Hustwit is currently touring with his third design documentary, “Urbanized,” which premiered last month at the Toronto International Film Festival. His first film, “Helvetica,” was released in 2007, followed by an homage to industrial design, “Objectified,” in 2009. The 85-minute "Urbanized" shows just a fraction of the almost 300 hours of footage that Hustwit and his team shot in more than 40 cities around the world. I sat down with him earlier this month before the Seattle screening of the film, and he shed some light on the process of making this trilogy of design documentaries.

When you started working on “Helvetica” in 2005, did you already have "Urbanized" at the back of your mind?

Absolutely not. When I was making “Helvetica,” I had no plans of making other design documentaries. It was a one-off project. I'd never made a film before and didn't know what I was doing. I wanted to watch a film about fonts, but there wasn't anything out there so I decided to make the movie I wanted to see. Once “Helvetica” had such a great reception and was financially successful, I wanted to do another film and learn more about the process of doing a documentary. The next idea was “Objectified.” I really liked the ideas, music and visuals of “Helvetica” – the overall aesthetic – so why not use the same type of approach in a different area of design? I was also obsessed with product design and the stories behind objects.

I remember the moment when I had just started “Objectified” and I realized I was making” Helvetica II.” That's when I had the idea of it being a sequel to “Helvetica,” and at the same time I envisioned a third film in the series. The only reason why I chose cities and urban design is probably because I was traveling so much at the time. The three topics seem to work as a series, but for me, it just feels like one big film. It just took six years to make it.

[caption id="attachment_227590" align="aligncenter" width="445" caption="Mayor Enrique Peñalosa biking through the streets of Bogota. Image courtesy of Swiss Dots Ltd."] [/caption]

[/caption]

Are there any interviews in “Urbanized” that stand out for you?

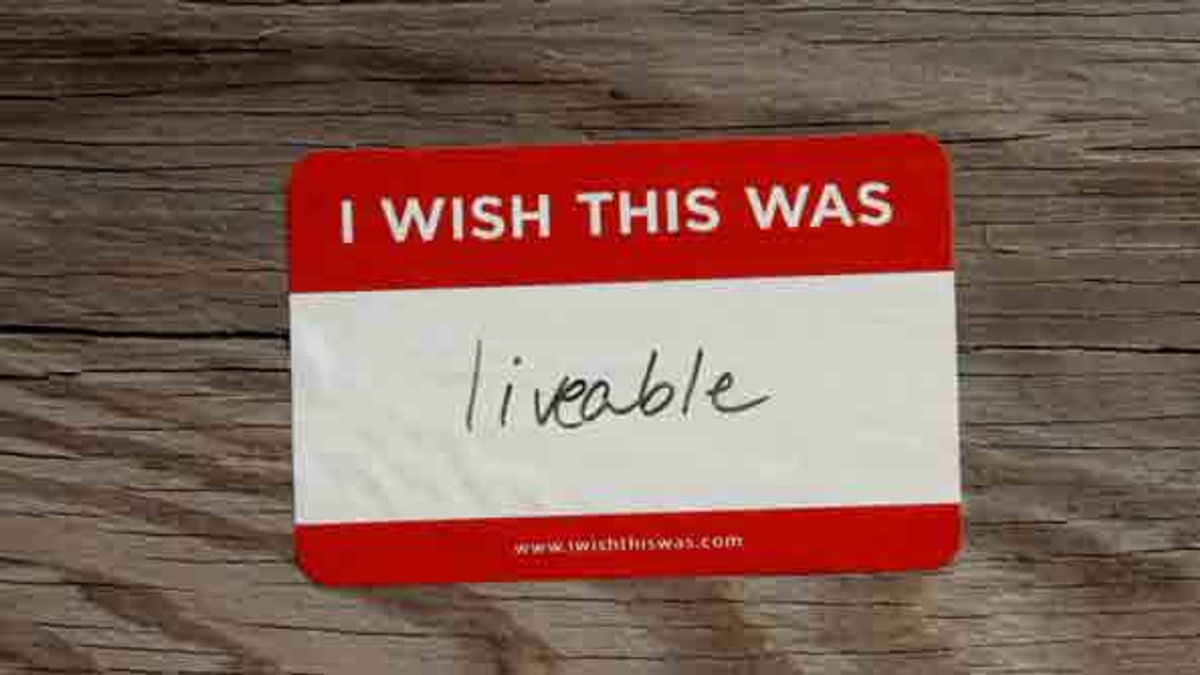

I love all the interviews in all the films, that's why they are in the film. But there are definitely some that people respond to when they watch the film. Most of all Enrique Peñalosa, who is the former mayor of Bogota. He's got some great lines in the film, like “There's no constitutional right to parking.” He's really charismatic and has some really commonsense ideas about using the city as a tool to create equality, democracy and social equity. I also got to interview Oscar Niemeyer, the legendary Brazilian modernist architect. He's about to turn 104 and is the oldest living architect in the world. He's got his grandchildren working in his office. That was a big honor for sure. Candy Chang is a public visual artist who has done some really powerful but simple projects to engage people in the community to get involved in shaping it.

[caption id="attachment_227591" align="aligncenter" width="445" caption="Candy Chang's street art project in New Orleans. Image courtesy of Swiss Dots Ltd."] [/caption]

[/caption]

How did you put the film together?

What was interesting with this film was how social media, especially Twitter, has changed the way I make films. Of course you get the word out about screenings, but I used it as a way to find ideas and projects to include in the film, such as a train station redevelopment project in Stuttgart that turns ugly. That project (Stuttgart 21) I found through Twitter. Two weeks later we were in Stuttgart on the day that all hell broke loose. The other way I ended up using it was that a lot of times I just wanted a couple of shots of a particular city to add to the visual fabric of the movie. We did this five or six times. "Hey, is there anyone in Rome? I'd like a few shots of the Piazza Navona." They shot it and uploaded that night. I did that in Melbourne, Athens, Chicago, a couple of cities in Florida. Especially at the end of process when we were editing, and under a deadline, normally I'd just have to dream of getting a shot of the Piazza Navona. This totally changed the process when I could just tweet it and reach people around the world and get them to contribute to the project.

[caption id="attachment_227587" align="aligncenter" width="445" caption="Model of proposed redevelopment of Stuttgart train station. Image courtesy of Swiss Dots Ltd."] [/caption]

[/caption]

I read a review in the L.A. Times that praised the movie but was a little indignant that L.A. had been left out. You include footage from more than 40 cities. How did you choose which ones?

There are so many cities we couldn't go to that are not in the film. Our approach with "Urbanized" was not to look at specific cities. It was to look at specific, universal issues and then look at specific projects around the world. Universal issues that face all cities: We all need a roof over our head, we need clean water and sanitation, we need mobility and ways to get around, we need some place to work and we need places to relax. Whatever you want to talk about in a city, it all pretty much boils down to one of those five issues. Then we look at how different cities are dealing with them. In a way, we are making a composite city. I couldn't think of any other way to structure it.

What kind of response have you gotten to “Urbanized”?

I think in a way, of the three movies, “Urbanized” is the most personal. Everyone lives in a city and they know what they like or don't like about cities. Everybody wants to change their city and make it better, but a lot of people don't really know how to go about doing that. In terms of the response to the film, I've never had a film where people were applauding during the film when there was something that they agree with. That's something I've never experienced.

Is there a message you want people to take away from the film?

A lot of it is about how cities should work. The projects take so long that it's a detriment because political winds change and citizens who should be involved in the project don't even know it's happening until the bulldozers start rolling in. It's never the case where government is going to ask "What projects do we need?" and really use the public as a compass. The main time the public interfaces with the city is when they are against something that is already underway. They are not leading a positive initiative to get something done. That's the takeaway of this film: Be more involved and critical about how you want your city to be.

Do you think the trilogy has helped raise public awareness about the role of design in our environment?

At the screenings events we do, there is a certain amount of preaching to the choir. People who are going to spend $20 to see a film in a theater are probably designers or at least familiar with design. But when the films are broadcast on PBS and people are scanning through the channels and run into something, those are the circumstances where we get more exposure to people who aren't familiar with design. I've had a lot of people come up to me and say, "Netflix suggested I watch 'Helvetica.' A movie about a font? What? Now I look around and all I see is Helvetica."

Watch the “Urbanized” trailer:

Shares