Gavin Bowd, the English translator for Michel Houellebecq, was working on the controversial French novelist’s “The Map and the Territory” — Knopf will publish the first American edition in January — when he came to a chapter about a character who’d decided to commit suicide at a legal euthanasia clinic. As the book’s narrator put it, the clinic’s medical staff was “going to 'se faire des couilles en or,’” Bowd recalled. “Literally: they were going to turn their balls into gold.”

Herein lies the translator’s dilemma. Bowd’s mission is stay as loyal as possible to the original text. But in this case, a strict translation would be ridiculous. “I translated: they were going to make a killing” in fees, Bowd added via e-mail from Scotland, where he teaches French at the University of St. Andrews. “In the context, I prefer that.”

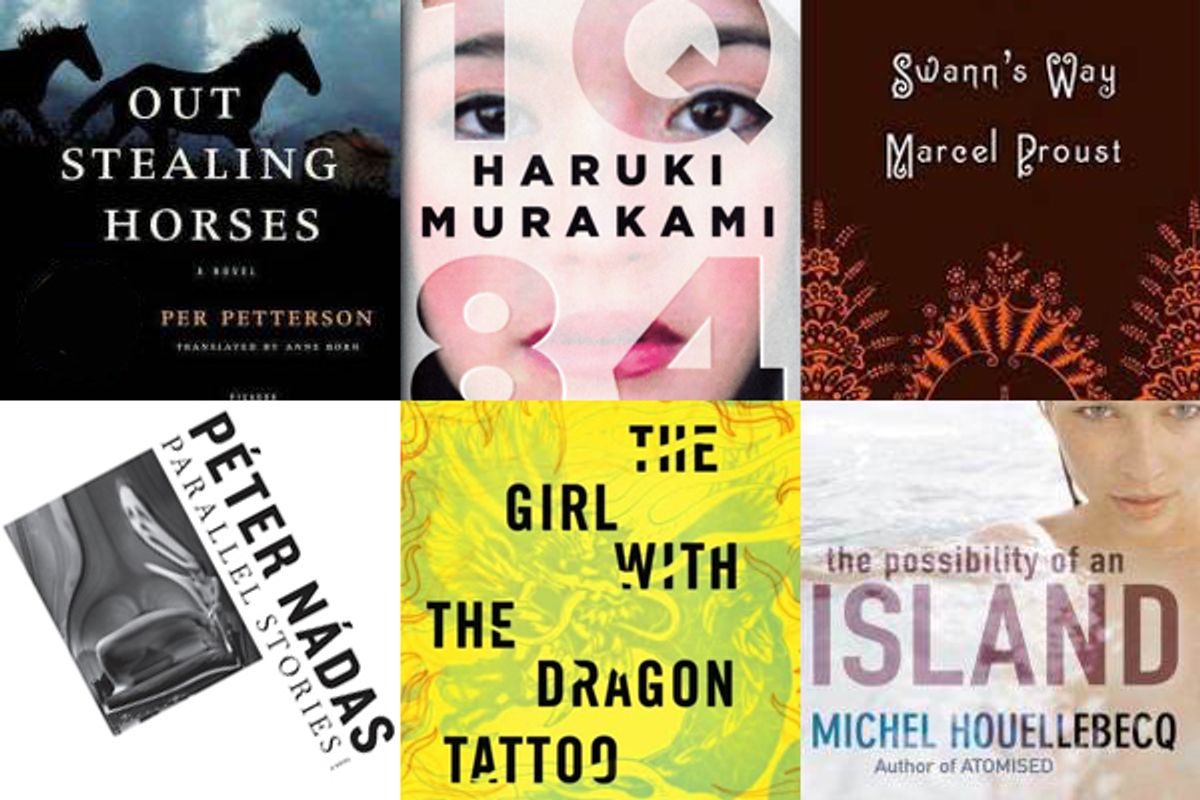

These are the kind of decisions that translators make on a line-by-line basis. Readers don’t notice these artful adjustments, but their enjoyment of literature in translation is dependent upon them. But even as the American appetite for foreign fiction — Stieg Larsson’s “Millennium trilogy” remains a bestseller, Haruki Murakami’s just-published “1Q84” is a huge hit, and the months ahead will bring big new English editions from international stars like Umberto Eco, Roberto Bolaño and Peter Nadas — the translators of these works typically labor in anonymity. Some even crave it.

“We’re lucky if we’re invisible,” said Steven T. Murray, who translated all three Swedish-language novels in Larsson’s trilogy, in an interview from his home in New Mexico. Murray was so bothered by a British publisher’s decision to rewrite much of his work that when the books started appearing in English in 2008 he replaced his credit with a pseudonym (Reg Keeland).

“It’s true in America, but it’s even truer in Britain, that there is a kind of cloud of disapproval over translators and translations,” said David Bellos, a translator of novels by Ismail Kadare and Georges Perec and the author of the new book “Is That a Fish in Your Ear? Translation and the Meaning of Everything” (Faber and Faber). “Reviews in the [Times Literary Supplement] of translated books — if they mention the translating at all, it’s to disparage it. Bit by bit over the years, I’ve come to realize that these are very effective devices for holding the foreign at bay. It’s a way of comforting yourself: 'Oh well, I only read English, and I don’t really have to take these books from elsewhere terribly seriously because they are only translations.’”

Though he chuckles about it — “Bellyaching is part of the community, I’m afraid,” he said — Bellos has a good case when he says that translators deserve better. “A long novel — maybe you get $10,000, in dribs and drabs. A bit on signature, a bit when you deliver the manuscript, a bit when it’s published. How many of those have you got to do in a year to make that a living? More than is really conceivable to do well,” he said. “You would have to translate at 90 miles an hour and not revise. Most literary translators don’t want to do that, even if they could. You can’t really live as a literary or book translator in the English-speaking world as a full-time job and also sleep.”

But sleep doesn’t come if you’re forever working through word puzzles. And this is what translators do, day after day.

Lydia Davis, a lauded American fiction writer who has translated Proust and Flaubert, said she encountered several such riddles when working on her 2010 translation of “Madame Bovary” (Penguin). For instance, she said in a phone interview, Flaubert describes a particular purplish, black plum that grows in the Normandy region of France, one that “is only known by its French name because it’s not exported. So that really has no translation.” In the end, Davis recalled, she opted for the unadorned “black plum.”

Some translators read a text from start to finish immediately before starting a translation, but Davis said she prefers an element of surprise.

“I had last read ‘Madame Bovary’ when I was 23 years old, so that was a long time ago,” she said. “I just start at the beginning and don’t read very far ahead at all. Maybe a page but often not that much, because I actually don’t want to know exactly what’s going to happen on the next page. There have been times, say, deep in the middle of doing the Proust translation where I didn’t even read a paragraph ahead, I didn’t even read a sentence ahead. It’s simply more exciting. There’s no drawback to this, because of course you’re going to do another draft and then another draft, so there’s plenty of time to go back over your work and change things in light of what you now know.”

Philip Gabriel, who, along with Jay Rubin, translated Murakami’s “1Q84” (Knopf) into English, has a different way of working. “I usually read the book straight through, then go back and translate a rough draft of about four pages per day until it’s all done,” he said in an email. “I try to spend some time previewing the next day’s pages so I don't get too caught up on particular passages.”

But the word puzzles still manage to appear in every chapter. As Gabriel put it, “To give you some idea of the sometimes mundane nature of the discussions translators have, I remember a long-running discussion with the editor about ‘lavatory’ vs. ‘bathroom.’”

Tiina Nunnally, who translated Peter Hoeg’s Danish-language “Smilla’s Sense of Snow” and Henning Mankell’s Swedish “Chronicler of the Winds,” said she and her husband, Larsson’s translator Murray, liken their work to that of a musician.

“You start with a text just like a musician starts with a composition, a work of music. And then your job is to play it for the listener so that they hear what the composer or the author intended. It takes a lot of practice to be able to do that,” Nunnally said. “It requires a talent for transforming words from one language into another, and doing it so that it doesn’t become apparent that the reader is reading a translation. That’s the real trick, because Americans especially have a certain wariness about reading a translated work. I can’t tell you how many people have said: ‘Well, I’d pick it up, but I could see it was a translation so I didn’t really want to read it. I knew it would sound awkward.’ That’s our goal, to make sure that it doesn’t sound awkward.”

Likewise, Don Bartlett said that he’s made “hundreds of decisions” each day as the translator for Norwegian novelist Per Petterson’s “It’s Fine By Me,” which Graywolf Press will publish next fall. “There is very little that is automatic about translation, and sometimes the simplest utterances, in a dialogue, for example, can take a long time to find a satisfactory equivalent for,” he wrote in an email. “... In terms of knotty language problems, I can remember being taxed by a woman’s name, Signe, which also means to ‘bless’, and the wordplay involved in a kind of tight, rhythmic chant to her. The English translation has the same coherence, feel and warmth, but of course not the constant repetition of ‘S/signe.’”

Not too long ago, Imre Goldstein completed a translation of Hungarian novelist Peter Nadas’ 1,100-page “Parallel Stories," which comes out in the U.S. in November (Farrar, Straus & Giroux). Does Goldstein believe translators are appreciated, and properly compensated, for the work they do? “I do not,” he said in an email from Tel Aviv.

But, Goldstein added, “I reach back to the theater where I spent more than four decades, to draw not a conclusion but only a parallel. Potentially the most gratifying and elevating teamwork, a theatrical production, as everyone knows, requires the input of many collaborators. Often, reviewers write only about some, say, the director, the actors and the costume designer, leaving out others, such as the composer, the musicians, the lighting designer, fight choreographer and all the invisible but indispensable tech crew, without whom there would be no production. When, as a translator, I am not mentioned in a review, I console myself by assuming that the reviewer read the text as if it were the original.”

If English-language translators feel underappreciated in America, they might want to avoid Bellos’ book, in which he notes that “Japanese literary translators have much the same status as authors do in Britain and America. Many author-translators are household names, and there’s even a celebrity-gossip book about them: 'Honyakuka Retsuden 101,’ or ‘The Lives of the Translators 101.’”

“They’re rock stars,” Bellos added as we talked on the phone. “Maybe it’ll fade away over the next century, maybe it’s just something of a fossil. Or maybe the Japanese have got it right, and we should treat all translators as rock stars. I wouldn’t mind.”

Shares