Remember the scene in “Reality Bites” where Wynona Ryder is asked to define irony? “Irony. Uh ... Irony. It's a noun. It's when something is ... ironic. It's, uh ... Well, I can't really define irony but I know it when I see it!” Irony is one of those terms that can be hard to define, particularly since it is often used interchangeably with other related (but distinct) terms like satire, sarcasm, cynicism and snark. Why is irony such a difficult concept to grasp?

Philosophy professor Jonathan Lear sets out to answer this question in his new book, “A Case for Irony,” attempting to redefine and flesh out this term from the pat and the vague. In Lear’s view, irony is not just about humor: It's meant to serve as a sobering mirror to our lives and actions, revealing and reaffirming to us our passions and beliefs. It shows how exactly we measure up to our professed ideals, all in an effort to strive for excellence – to become better at whatever it is we devote our lives to. Irony asks us, in a fundamental way, “Am I really who I say I am?”

Lear spoke with Salon over the phone to discuss this obscured meaning of irony, its connection with erotic impulse, its usefulness in the political arena, and Lincoln’s smarting humor.

You set out to define irony in this book and find that it has little to do with what is commonly understood by the term (i.e., wit and detachment). What do you understand irony to be?

I’m trying to go back to what I think is an old conception of irony. You can find it in Kierkegaard if you look hard, and he found it in Socrates. It’s almost the opposite of what irony is taken to be in contemporary culture, although if you start to look and think about it, one can see how they’re related.

How do they differ and what’s the connection?

I was just reading the paper the other day, and you begin to wonder: Is there any such thing as a euro anymore? Or when was the last time we had a president of the United States? Or among all our liberals, can we find a real liberal? One of the points of these questions that I think is very important in the central usage of irony is that it is not the opposite of earnestness. When you’re asking these questions, you’re not just being a smartass, or saying the opposite of what you mean in order to be recognized as saying the opposite of what you mean. These questions can be asked with intense seriousness, deep earnestness. You can be saying exactly what you mean and not the opposite of it. And unlike the contemporary culture’s understanding of it, it can be asked in the sense of “this really matters to me.”

It’s very complicated. When you say something like, “Is there a euro anymore?” or, “Is there a president anymore?” – on the one hand, you are, of course, somewhat detached from the current engagement, or that question wouldn’t even arise. But I think in its most important sense, it’s not meant to be a form of detachment. It’s because ultimately having a real president of the United States, or having a real liberal, or a having a solid currency matter to you that these questions arise. It’s not a question of, “Like, I’m not going to be attached to anything,” or, “I’m going to show how detached I am.” It’s actually quite the opposite. In its primary use, irony is a sign of how much things can matter and ought to matter and what they really ought to be like. So, I think that although there may be a moment of detachment in irony, it’s really, deeply in the service of trying to reattach to a more serious and committed way of living. And that, I think, is a complete 180-degree, just opposite view of contemporary culture’s understanding.

So if it’s not fundamentally about detachment, how is irony experienced? You write that it is linked with ignorance. How so?

Irony has to arise in the first person [i.e., has to be directed at oneself first]. There are a lot of derivative uses about how it’s about striking out at other people, or the world, or what you think about it. But, the really core issue of irony is when it hits you about yourself and the living of your life. Am I really succeeding as the kind of person I want to be? What outstrips what I’m now doing? Where do I stand with respect to that? What am I going to do with that? That, I think, is the key experience of irony.

In other words, irony is sort of like having an identity, or existential crisis where you question your ideals and purpose in life and whether or not you are actually living up to those, but this crisis moment doesn’t necessarily have to be a negative experience because it reveals or reaffirms the things/values we deem most important to life and who we are as individuals. Do you believe, then, that humans are always striving for excellence? That complacency is not inherent in us? Transcendence seems to be a running theme in your book.

I think there’s a tendency toward both. The thing that is more surprising is this kind of hopefulness and striving, which seems to me to be built into the kind of creatures we are. When you think about your own ambitions [and the steps you take to fulfill them], there’s a kind of excitement in that. That excitement, Plato thought of (and Freud picks up on this) is part of your erotic life. Your Eros has gotten into doing this thing, or being this kind of a person, and there’s something just exciting and alluring and fun about it. It’s that kind of erotic pull that, in a way, won’t let you rest content with being mediocre. Insofar as you fall into routines, that original love affair with what you might become makes you discontent with settling for the routine. That’s the moment of conscience.

On the other hand, we’re born helpless. It’s not just a psychological fact about us, I think it’s a structural fact. We’re very dependent for a long time. We get inducted by parents and teachers into a natural language and routines, everything from potty-training to eating food at a dinner table to not pushing to sharing, and all these things. It’s in our nature that we have to be inducted into society’s patterns and rituals and habits. There’s a tendency toward complacency – of fitting into the group, not questioning things too much. It’s an inherent part of who we are, and yet there’s also this countervailing tendency to disrupt that, to be discontent with it, to not settle for it. You can see this. Once you start looking for it, it’s everywhere. This [moment of discontent] is something important about being human.

You mentioned Socrates earlier; do you see any great ironists today?

That’s a really good question. No, I do not. I see situations I think of as ironic, but I have not seen public figures deploying it. In terms of statesmen and public figures, Abraham Lincoln was an ironist. He had a wonderful, self-deprecating humor, and some of his humor is ironic in my sense. At some point he says that people say that slavery is a good, but the strange thing about it is it’s a good that people only pursue for others – they never pursue it for themselves. Now that’s beautiful. That’s irony. That level of wit. But you see there’s something very deep in that. What I love about it is that anybody who heard it, if they could laugh at it, [then] it also stung them. It can get into your soul. “How is it that this could be a good if we’re always pursuing it for other people?” There you’ve got irony that’s earnestness. It’s got all the marks and features of it. But I don’t see this in the contemporary crop of political leaders.

[Irony] is being caught by something you already take yourself to believe in, and then the sudden sickening sense that the commitment is so much more demanding than you originally took it to be. You’re caught because the value matters to you, but then you come to see that your understanding up until now has been somewhat complacent. That’s the sting. “Whoa! What do I have to do now? Because on the one hand I’m already committed to it, and on the other I have a sudden glimpse that I don’t yet understand the it is that I’m already committed to but have a sense that it outstrips what I’m currently doing.” You start to get that anxious sense of “Holy mackerel!” That’s the sting.

And irony’s evil twin, snark, is just all sting?

Trying to be snarky, and above it all, and “nothing really matters,” and “it’s just naive to think that something matters” – this is the opposite of irony, as I understand it, and I think it’s an attempt to stay away from it. It’s too scary, too dangerous, too demanding.

To commit yourself to anything worthwhile?

Exactly. I think it’s a shallow attempt to isolate yourself from a recognition of commitment. You know, what is your life about? Do you want it to be about anything? I think it’s a fearful sense of “Well, maybe I can insulate myself from that question if I look at it as being naive.” I just think it’s a pretty thin defense. It doesn’t really work that well.

Was there ever a golden age of irony?

I don’t know and I’d be a pompous ass if I started to go on about the whole sweep of intellectual history. I assume there are other great ironists that have come along – Swift, Montaigne. There are, I’m sure, plenty others. The truth of the matter is is that I’ve lived in the company of Plato and Aristotle and Kierkegaard.

[However,] I think our time is ripe for irony around issues of what it would be to be a democracy. The recent Supreme Court decision where corporations get counted as persons and can contribute as much to campaigns as they want – is this what we mean by free speech? I’m not an expert on that ruling, but it seems a very poor ruling in terms of the free speech that a democracy needs.

Do you think that politicians are just fundamentally poor ironists?

How well does one do as a politician if you don’t fit into the demands of your political party? The demands of fundraising? How much of this is promoting a democracy and how much is interfering? My view is that there are tremendous social and political pressures against there being any ironist on the political scene. I think should one rise amongst us, he or she could be seen as a real leader.

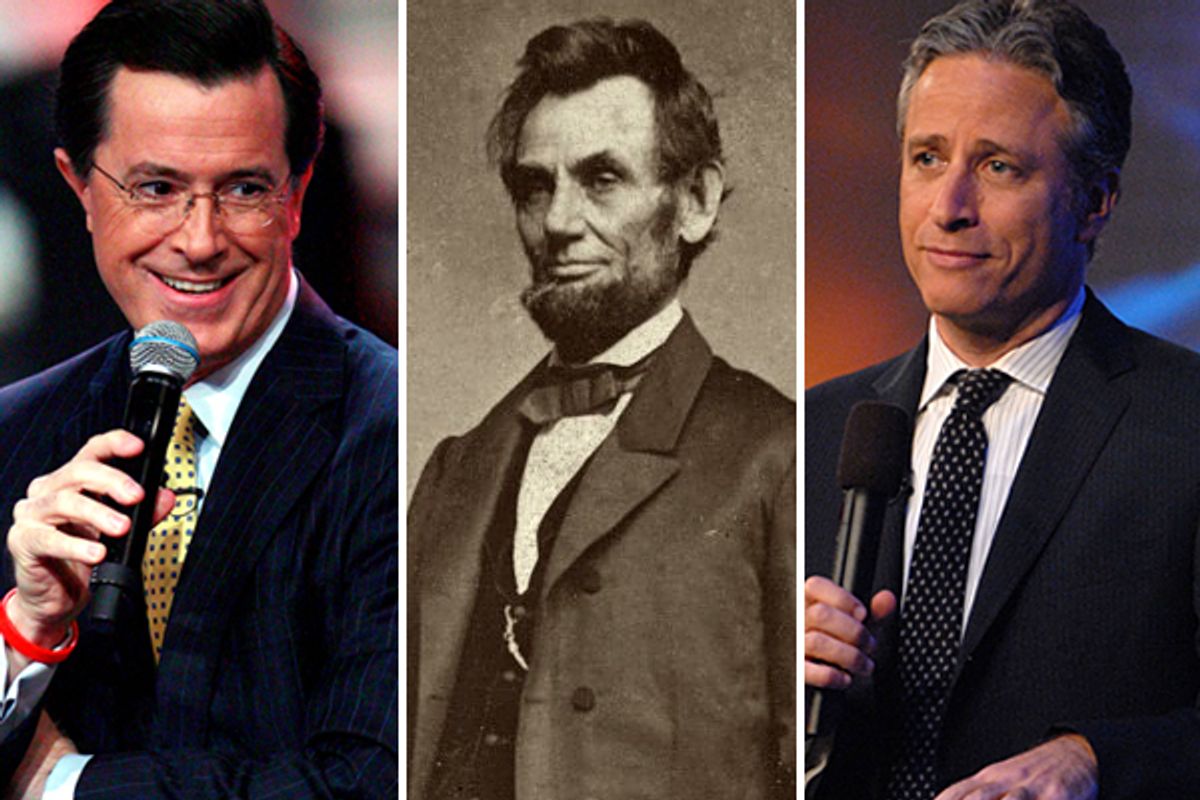

Do you consider satirists and comedians like Jon Stewart, Stephen Colbert or Bill Maher to be ironists?

I make a big difference between these three. I put Colbert and Stewart on one side, and Maher on the other. Maher is more snarky. He’s sort of preaching to the converted. He’s asking people who already agree with him to laugh at people who don’t agree with him, and, in itself, it’s a group activity. I think there’s less of that certainly in Colbert, and I think in Stewart too. There’s more of an attempt to play with ironic moments – especially the whole persona of Colbert, which is hilarious. But when [Colbert] looks straight into the camera and says, “Nation,” on the one hand it’s a very funny routine and it’s mimetic. He’s imitating others, and we recognize the imitation, and we enjoy the mimesis, and it’s pleasurable, but when he does that, is there ever a moment when one is stung by the thought: Well, what would it be to be a nation? What would it be for us to be a polity that could be addressed? Underneath the very real humor – and I’m not saying it’s always arising – but there’s a possibility of actually getting shaken up about this. I think Stewart does this as well, pointing out, in a hilarious way, the various ways our leaders can be hypocritical. Again, we laugh at the humor, and he’s very good at it, but I think that in laughing at the humor there’s a possibility for that kind of a sting – what would it be to either have a leader or to be one? Or to take responsibility for our elected officials? For Colbert and Stewart, there’s a possibility for irony that I don’t much see in Maher.

Shares