Looking at the most visible exemplars of epic fantasy -- from J.R.R. Tolkien to such bestselling authors as George R.R. Martin and Robert Jordan -- a casual observer might assume that big, continent-spanning sagas with magic in them are always set in some imaginary variation on Medieval Britain. There may be swords and talismans of power and wizards and the occasional dragon, but there often aren't any black- or brown-skinned people, and those who do appear are decidedly peripheral; in "The Lord of the Rings," they all seem to work for the bad guys.

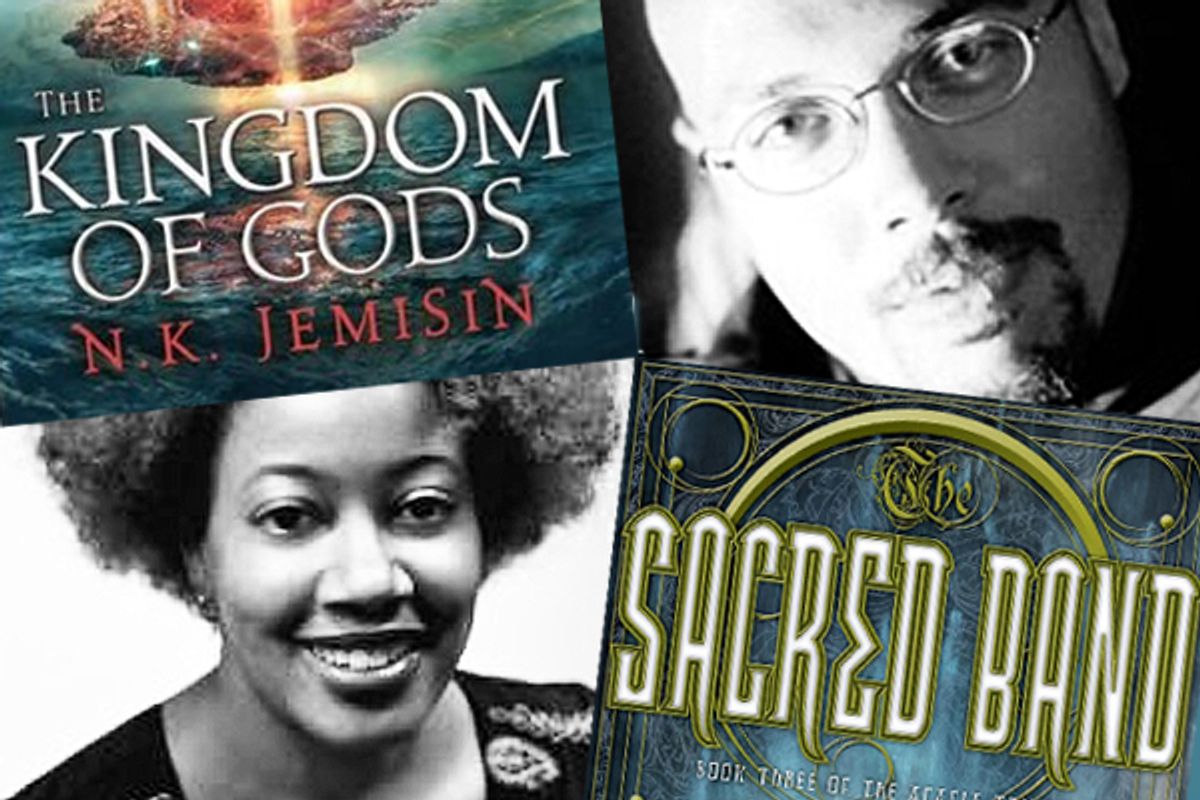

Our hypothetical casual observer might therefore also conclude that epic fantasy -- one of today's most popular genres -- would hold little interest for African-American readers and even less for African-American writers. But that observer would be dead wrong. One of the most celebrated new voices in epic fantasy is N.K. Jemisin, whose debut novel, "The Hundred Thousand Kingdoms," won the Locus Award for best first novel and nominations for seemingly every other speculative fiction prize under the sun. Another is David Anthony Durham, whose Acacia Trilogy has landed on countless best-of lists. Both authors recently published the concluding books in their trilogies.

Although they came to the genre from different paths, both Jemisin and Durham have used it to wrench historical and cultural themes out of their familiar settings and hold them up in a different light. "I never felt that fantasy needed to be an escape from reality," Durham told me. "I wanted it to be a different sort of engagement with reality, and one that benefits from having magic and mayhem in it as well."

In Durham's trilogy, four royal siblings are deposed and then fight their way back to the throne in an empire presided over by the island city of Acacia. Their dynasty's power resides in a Faustian bargain made with a league of maritime merchants: the League supplies a rabble-soothing drug in exchange for a quota of the empire's children, who are sent off across the sea to meet an unknown fate. As promised, "Acacia" is a sweeping yarn filled with adventure, intrigue, sorcery and battles.

"There's a little bit of the Atlantic slave trade in there, and there's a bit of the Opium Wars and quite a bit of Halliburton," Durham said. When set in the real world, such topics come "weighted with particular agendas and political orientations." Readers often approach them with established opinions -- or are so convinced they already know what the author is going to say that they never bother to approach them at all. When similar themes arise in an imaginary world, said Durham, "I have some readers who are quite liberal and some that are more conservative than I am, but they still engage with the book that I wrote, with all the components that are at play in it, in a way that I think they wouldn't if they perceived me to have a political agenda right from the start."

While Durham came to writing epic fantasy after publishing two literary novels (he has an MFA from the University of Maryland) and a historical novel about Hannibal's march on ancient Rome, Jemisin has been a self-identified "black geek" since childhood. She started out reading science fiction, deeming fantasy to be insufficiently "real," a notion she now considers "bizarre." Furthermore, "I was reading almost exclusively male writers." Her youthful attempts at writing her own stories hit a snag when her father prompted her to create a black female character, and she found she couldn't do it. "I really didn't know how to write from the female perspective, even though I was female." An active search for more innovative science fiction led her to the work of Octavia Butler, "and my consciousness was utterly changed."

Perhaps because the notion of envisioning a different future is baked into the form, science fiction is known for fostering such groundbreaking black authors as Butler and Samuel Delany. (Although, Jemisin pointed out, the first book she read by Butler featured no author photo and a cover illustration of white women, a practice known as "whitewashing.") Much of epic fantasy -- usually set in a preindustrial world -- is more conservative. For example, the genre's founding author, Tolkien, expressed a keen nostalgia for Anglo-Saxon rural life in the feudal past.

Still, some authors have tried to expand the genre's borders. Both Jemisin and Durham cite Ursula K. Le Guin's Earthsea books as an important influence. Le Guin, the daughter of a pioneering anthropologist, set her young-adult series in an archipelago of islands, and based its culture and religion on Asian and Native American models. Her primary characters in those novels were people of color.

Nevertheless, when Jemisin decided to write her own epic fantasy in grad school, she found herself abiding by some of the genre's most shopworn conventions. Her main character was a man. "I was thinking it had to have a quest in it, with a MacGuffin of Power being brought to a Place of Significance," she said. The book didn't quite work, so she set it aside, and when she returned to it a few years later, she decided to start over. She made the main character a woman and, in an even more marked departure from the norm, she decided to have that character narrate the book in the first person. "I knew that what I was writing was inherently defiant of the tropes of epic fantasy," Jemisin said, "and I wasn't sure it would be accepted."

Jemisin's series, too, is set in the capital of an empire that has been run by an aristocratic clan for generations. The power of the Arameri family, however, resides in the gods -- specifically a pantheon of deities whom they have imprisoned and enslaved. The narrator of "The Hundred Thousand Kingdoms" is the daughter of a renegade member of the clan who ran off with a foreigner. Raised in a remote kingdom with its own fiercely independent customs, she returns to the capital seeking information about her mother and, once there, becomes embroiled in vicious palace intrigues.

When Durham decided to write an epic fantasy, he set out to recapture the enchantment he felt as a 12-year-old, discovering Tolkien at his father's house in Trinidad, while "brushfires and buzzards" ranged over the neighboring hills. Jemisin, on the other hand, based her trilogy on "the old-school epics: not Tolkien, but Gilgamesh." The gods in her imaginary world evoke the squabbling divine families of the world's great myths: "The ancient tales of mortals putting up with gods and trying to outsmart gods, of trickster gods outsmarting other gods: That's the basis of my work."

Despite such differences, what's most striking about the fictional worlds Durham and Jemisin have created is how cosmopolitan they are. Their cities are populated by people of different races and religions, mixing together and comparing their respective values. They bridle at the limitations of class. Economics drive many of their actions, and the conflicts that inevitably arise can't be easily parsed. "The strange thing about some of [the most popular epic] fantasy worlds," Durham said, "is that it does seem that the entire world is northern Europe. That's all there is. It's always easy for me to engage with that, but then a part of my mind is also wondering, 'What happened if you spin the globe?' What are the people doing there? How is their history been shaped by the magic of that world? There's something exciting about acknowledging that everybody is not the same and that affects their struggles."

Jemisin finds deeper problems in "certain expectations of the genre that are rooted in Western cultural assumptions that are not necessarily true. For example: the whole good-versus-evil focus, the binary. You see that in so much of epic fantasy. The Dark Lord is really bad, we know this. Because he's dark. Well, did you do something to him? Doesn't matter, he's dark. That's why he's bad and that's why you've got to go kill him. That kind of thinking I inherently do not trust."

If these writers can bring fresh perspectives to the genre, the genre reciprocates by bringing them new and more varied readers. Durham's second book, a literary novel titled "Walk Through Darkness," about an escaped slave and the man tracking him, "never made it to the front of the store, really, because it was immediately shelved as an 'African-American novel.'" Now, "my stuff is being read by more and a wider range of people than it was in the early days."

Jemisin has been annoyed to learn that her first novel sometimes gets shelved in the same section, which means that readers searching the science fiction and fantasy area can't find it. "The inherent danger of that section," she said, "are the ideas that, a) only African-Americans would be interested in it, and b) African-Americans are interested solely because there is something African-American associated with it -- usually the writer. I don't see the novels of white authors who write black characters getting shoved into that section." This is all the more irksome when, as was the case with her first novel, people assume her narrator is black; Jemisin envisioned the character and her people as similar to the Incas. "Just because I am black," she said, "does not mean I am always going to write about black characters."

In fact, the epic fantasy genre makes an imaginative departure from the contemporary (or historical) African-American experience feel less politically charged. Although one of Durham's royal siblings comes of age amid a dark-skinned people living on a savannah, the siblings themselves are brown with straight black hair. (He describes them as "sort of Mediterranean.") Because slavery in Acacia isn't tied to race, he can explore its consequences, as well as the effects of colonialism, apart from the issue of skin color.

"The genre can go many, many more places than it has gone," said Jemisin. "Fantasy's job is kind of to look back, just as science fiction's job is to look forward. But fantasy doesn't always just have to look back to one spot, or to one time. There's so much rich, fascinating, interesting, really cool history that we haven't touched in the genre: countries whose mythology is elaborate and fascinating, cultures whose stories we just haven't even tried to retell."

Shares