You’ll find lurking in every media-maximized sex scandal a man who feels himself in one way or another above the law. Look up “smug” in the political dictionary, and if the first entry isn’t Herman Cain, it will probably say Newt Gingrich, who eagerly pursued Bill Clinton concerning morals charges that may have paled in comparison to his own contemporaneous straying problem. Oops.

Now, let’s compare the other headline-grabbing sex shocker of the week: the concealment by Penn State University of Jerry Sandusky’s alleged fifteen-year rampage, in sexually abusing young boys. There is a common thread between the sordid Sandusky business and Herman Cain’s outrageous behavior when confronted with charges of serial sexual harassment: Power and the belief in one’s invincibility make for a dangerous elixir.

The question that these stories of sexual misconduct raise is a peculiarly American one: Why do our people handle such episodes so badly? The answer lies in the public’s inability to reconcile an admiration for powerful men and powerful institutions with its inevitable consequence of corruption. Blind trust and unalloyed admiration create the atmosphere for abuses of power, for covering up misconduct, and even excusing it when it is revealed.

Herman Cain is merely the most recent in a long list of defiant politicians accused of sexual misconduct. Abraham Lincoln didn’t live long enough for consorting with prostitutes to tar his reputation. James Buchanan lived too soon to be presumed gay, though he pulled a Joe Paterno in protecting his close associate Dan Sickles, adulterous congressman and later Union general, who traveled to London on state business accompanied by his favorite prostitute.

Andrew Jackson and his wife Rachel were smeared for their alleged bigamy, having “accidentally” lived as husband and wife for years before her divorce became official. And, as we know, Thomas Jefferson had to wait two centuries, until the advent of DNA, for the private life he implicitly denied to light up the news cycle.

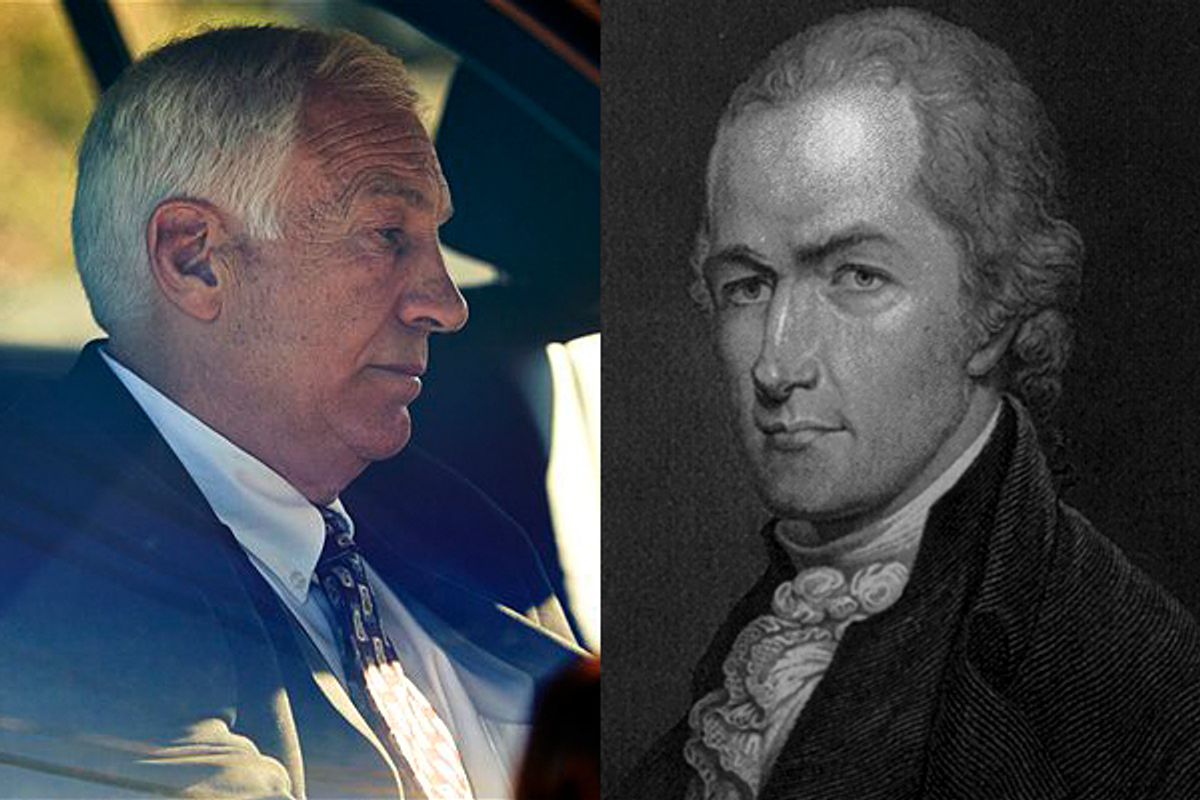

Before them all, though, it was Alexander Hamilton who established the pattern for the national politician’s good ol’ American sex scandal. Hamilton’s problem was adultery. Smug like Cain and a larger-than-life political fixer like Coach Paterno, he was caught sleeping with a married woman while his wife was out of town. The affair took place in 1791, during Hamilton’s years as President Washington’s secretary of the treasury, though it was only revealed in 1797, when more damning “evidence” surfaced through the column of a scandal-mongering journalist. Hamilton’s political opponents had agreed to keep quiet about his private behavior during the intervening six years, but remained silent no longer when the charge of misuse of federal funds was added.

A trail of clandestine payments led to James Reynolds, a former Treasury Department employee and the husband of Hamilton’s erstwhile mistress. Hamilton admitted to adultery, while declaring in his own defense that he had never misappropriated government money when he paid off the affronted husband to buy his silence.

How Hamilton handled the charges is what makes the scandal relevant to this week’s news. As a skilled attorney, he wrote a 100+ page pamphlet justifying his actions. Confessing only to an “indelicate amour,” initiated by Mrs. Reynolds, which he now regretted, he insisted that his public reputation remained spotless, because he had never abused his office, had never stolen any money, and had never profited from his position as head of the Treasury Department.

On the other hand, Hamilton’s windy defense reminds one of the fumbled strategy used by Cain and his campaign staff. Hamilton painted himself as the victim of a conspiracy in which James Reynolds contrived to entrap him, literally pimping his wife in order to gain the advantage over the otherwise incorruptible executive. Hamilton also denied personal culpability by unabashedly blaming all undeserved publicity on a political environment generated by the machinations of Jeffersonian Republicans.

Cain, as we have seen, chose to distribute the blame liberally, in the vain (yes, both definitions of the adjective apply) hope of deflecting the shafts aimed at him. He accused Rick Perry’s staff of leaking the story, harped on the “Democrat machine,” and claimed that at least one of his accusers had gone after him for money or fame.

Hamilton’s defense backfired, and it’s not likely that Cain’s tactics will save him either. A high-placed Federalist, rather than defer to the leader of his party, chose instead to point out that Hamilton was trying to “creep under Mrs. R’s petticoats.” He mocked Hamilton for his ploy of misdirection, chiding him for what amounted to an unmanly cowardice–and no one in early American politics was more self-consciously macho than Hamilton. The newspapers likewise took him to task for his hypocrisy. A writer asked readers to judge whether it was possible to clear one’s name when accused of breaking one of the Ten Commandments (Thou shalt not steal) by openly admitting to having transgressed upon another (Thou shalt not commit adultery). “Does one sin wash away the other?”

In the end, Hamilton decided that the only way to repair his reputation was to engage in an “affair of honor.” So he accused James Monroe, the most hot-tempered member of the Congressional investigating committee, of leaking the Reynolds affair to the public, and he challenged the Virginian to a duel. Ironically enough, Aaron Burr interceded, and helped the two find a way to avoid the dueling ground.

The prototypical American political sex scandal reveals something fundamental about their nature. While comedians and pundits have made much of Herman Cain’s referring to himself in the third person, they have missed the significance in his choice of language. Not only is it a holdover from how royal personages refer to themselves (the royal “we”), but it also demonstrates that Cain has sought to divide himself, as Hamilton did, into a public persona and Cain the private person. Cain the candidate ("Herman Cain") expects, like Hamilton to be judged solely on the basis of his public conduct.

Cain also seems to think that the larger-than-life presidential aspirant is somehow above the mundane reality of everyday life. In his own mind, at least, he cannot be guilty, because having become “Herman Cain,” he is a public figure, whose private behavior attaches to a pre-candidacy legal entity who lacks a public profile or a responsible political identity. “Let’s keep him out of this,” he seems to be saying.

Cain’s rude dismissal of Congresswoman Nancy Pelosi as “Princess Nancy” is the sort of statement that might have led to an affair of honor in the distant past. But as it relates to the matter of the several women’s accusations against him as a textbook harasser, it is not Ms. Pelosi, but Mr. Cain, who uses the royal “we,” who imagines himself above the law.

Candidates and public officials routinely compartmentalize their lives. They routinely and conveniently rationalize outrageous behavior. Their learned comfort in the exercise of power on a regular basis invests (or infects) them with a sense of their invincibility and invulnerability—until they are caught and exposed. Though he might prefer to separate public and private, Herman Cain the non-candidate was the head of the National Restaurant Association (NRA). There, he held a position of power and trust, and it was the decision of a board of directors to reach a legal and financial settlement with women who brought charges against him. Cain’s case was taken out his hands and handled by the NRA.

Cain’s defense these days is unconvincing for reasons that seem obvious. First, all four women have to be lying to completely absolve him. Second, if a settlement was reached with two of the women, it is reasonable to conclude that the charges had legs. Third, Cain’s reckless claims that enemies have been trying to smear his reputation only work if the charges are not true. As Alexander Hamilton himself argued in a prominent court case of 1804, the charge of libel can only stick if the libelous statements are not true.

At Penn State, the football staff operated under its own distorted code of honor. It is now clear that a previous police investigation was made to disappear. The former quarterback turned graduate assistant Mike McQueary witnessed Sandusky raping a young boy in the locker room. On MSNBC’s "Hardball," the writer Buzz Bissinger (author of "Friday Night Lights") compared the Penn State football community to the Mafia; a more accurate comparison is to the rigid code of honor that exists in military communities. Paterno was more than a head coach–-metaphorically, he was the commander-in-chief of Penn State’s football program. It is probably the case at Penn State, as at many football-centered universities, that President Graham Spanier took his orders from Paterno, and not the other way around.

McQueary revealed what he observed to Coach Paterno, yet he lacked the will either to stop Sandusky from raping the boy, or to challenge Paterno when the crime was swept under the rug. Just recall the plot of the movie, "A Few Good Men:" institutions built on hierarchy and honor can lead to the abuse of power and suppression of truth. Unfortunately, when adoring fans of Paterno learned the truth, and gathered to support him, we learned that many Americans cannot handle the truth. Or, perhaps, that winning football games and raising millions ($170.5 million in 2010-11) is more important than facing something so fundamental and so uncomfortable as serial rape.

What mattered to Hamilton most was that his “honor” had been tarnished. He was more than willing to tell Congress behind closed doors that he had had an adulterous affair–if it would clear his name of the charge of misappropriating government funds. He assumed that a private disclosure among his male peers would settle the matter for good. But once the information became public, Hamilton was made a public laughing stock, and his only recourse was disclose his side of the story in his pamphlet–and then proceed to defend his honor on the dueling ground.

Today, politics (like big business) is without honor. Herman Cain became popular among the Tea Party crowd because he was arrogant, because he said outrageous things, and showed no embarrassment in being proven wrong, foolish, or ignorant. The arrogance of power is bad enough; it is worse when powerful men receive the backing and support of powerful institutions—a university, a restaurant association, the Catholic Church.

The voting public has been led to expect spotless candidates, which is a prime reason why negative ads poll so well. The idea that men can behave honorably at all times, and that their secrets should be kept because of some outdated–and frankly, perverted–code of honor, is a dangerous proposition. It sours the political environment, which is in need of a massive overhaul as it is. The idea that candidates are legally bought by corporate interests and association lobbies is a most unrepublican and unAmerican perversion of our founding principles. The lies and attacks, counter-lies and counter-attacks, that course through the election cycle epitomize the difference between the theory and practice of democracy.

It is this perversion which wreaks havoc on the principle that public servants should have good information, good ideas, applicable experience, and comprehensive understanding, if they are to give directions. Our skewed system, instead, had catapulted to positions of national visibility marginally informed, manipulative people who need to write their “core principles” on one hand to avoid the “Oops!” moment.

“Herman Cain” needs to look Herman Cain in the eye and face up to the fact that his past contains some ugly blemishes. Penn State fans need to move beyond blind idolatry, and recognize that Joe Paterno was the head of a morally corrupt outfit. And before they can become “people,” corporations have to exhibit a living, animated moral sense. Handle the truth, America.

Shares