CAIRO -- Sitting across from me in a downtown cafe, disgruntled democracy activist Ismail Wahby looks defeated. “Everything is failing,” he says.

In many ways, Wahby personifies the Western stereotypes about the mislabeled “Facebook Revolution”: He is an upper-middle-class 20-something who blogs in English, French and Arabic. After the ouster of Hosni Mubarak, he worked as community organizer with the Union of Progressive Youth, one of the many revolutionary coalitions formed after the dictator's fall. But as Egypt’s ruling Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF) became more oppressive in the months that followed, Wahby grew discouraged and withdrew from political activism. “I didn’t do a revolution for this shit,” he explains.

Wahby has a long list of grievances about the aftermath of Egypt's largely peaceful revolution last January, including the persistence of the State of Emergency -- which was supposed to have expired months ago -- and the failure of the opposition to present a unified front. But mostly Wahby is concerned with the dominance of the military in post-Mubarak Egypt.

Wahby’s pessimism is widespread. Since taking power last February, the military has perpetrated major human rights abuses and seems more interested in consolidating its own power than ensuring a democratic transition. Protesters have begun to set up tents in Tahrir Square in preparation for massive anti-SCAF demonstrations this Friday. A broad coalition of political parties and activists have threatened a prolonged sit-in protesting the military’s increasingly authoritarian ruling style and its unwillingness to share power with civilians. “The SCAF must step aside and respect the will of the people,” 45-year-old electronic engineer Mohammad Sayyid tells me from inside a tent he shares with half a dozen other men. Sayyid has been sleeping in the tent for over a week and promises that he will not leave the square until the military steps aside.

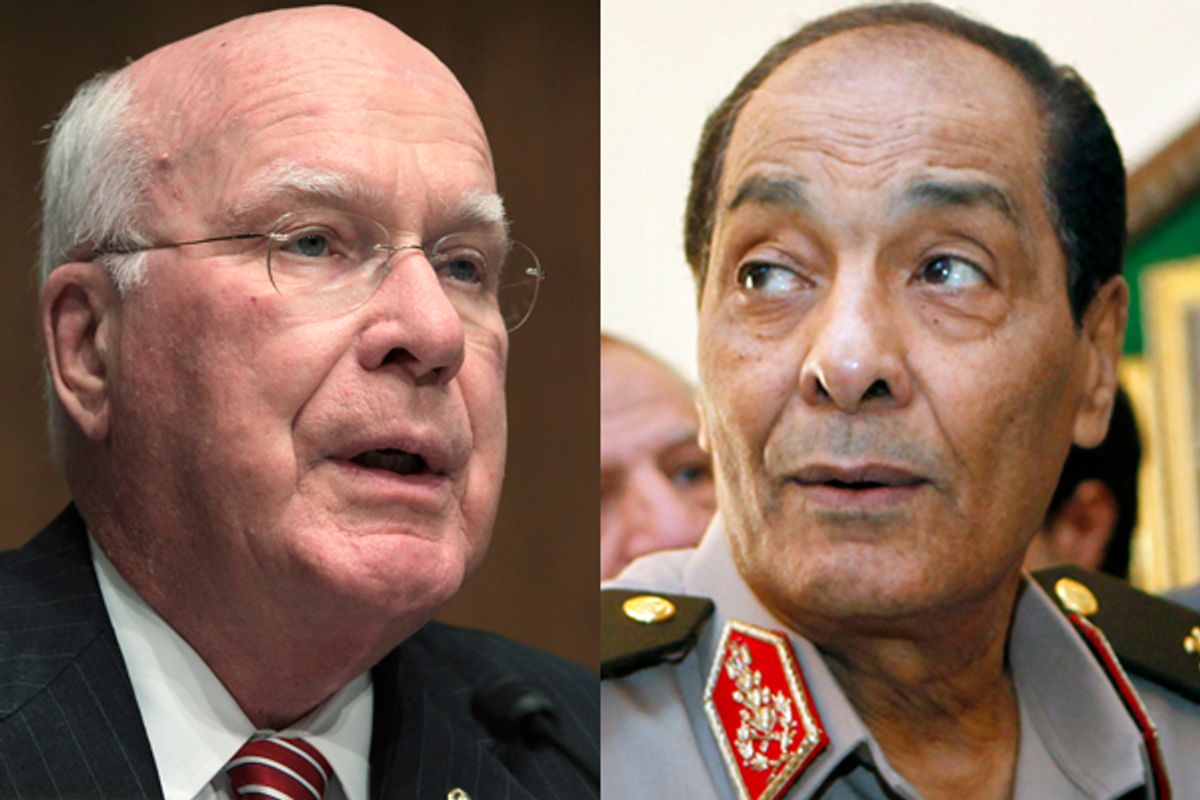

The showdown in Egypt coincides with a showdown in Washington, where Vermont Sena. Patrick Leahy is seeking to link U.S. foreign aid to the conditions of Egyptian democracy, a move that is opposed by the Obama administration. The proposal, contained within the Department of State and Foreign Appropriations Bill, passed out of committee last week with bipartisan support, and is expected to come to a floor vote soon.

After months of denial about the true nature of Egypt’s “democratic transition," the Obama administration shows signs of concern.

After Tahrir Square

In the nine months since Hosni Mubarak stepped aside, the Egyptian military has monopolized political decision-making. The SCAF has broken its promise to lift or modify the Emergency Laws, which have been in place since 1981 and give the state sweeping powers to detain citizens and restrict free speech, even though repeal of the laws was a central demand of the revolutionaries in Tahrir Square.

Since assuming power in February, the military has broken up protests, suppressed trade unionists, and imprisoned dissidents, journalists and bloggers. Human Rights Watch has accused the SCAF of subjecting between 7,000 and 10,000 civilians to military trials in the five months following the revolution. The recent imprisonment of blogger Alaa Abdel-Fattah drew the attention of the U.N. High Commission for Human Rights, which expressed concern about “what appears to be a diminishing public space for freedom of expression and association in Egypt.”

One of the more egregious incidents was the death of 27 Coptic Christian demonstrators at the hands of what many suspect to be military personnel on Oct. 9 at the Maspiro State Television building in downtown Cairo. The military blames the demonstrators themselves for the violence.

“Instead of identifying which members of the military were driving the military vehicles that crushed Coptic protesters, the military prosecutor is going after the activists who organized the march,” reported Sarah Whitson, the Middle East North Africa director of Human Rights Watch.

The U.S. government shrugs off these abuses, attributing them to the SCAF’s inexperience. At a Nov. 3 press conference in Washington, U.S. Ambassador for Middle East Transition William Taylor asserted that military abuse can be attributed to the fact that the military is unaccustomed to governing and may be overwhelmed. “[Governing] is not what the Egyptian military is trained to do,” explained Taylor.

Nadeem Mansour, the executive director of the Egyptian Association for Economic and Social Rights, a Cairo-based NGO, called Taylor’s assertion baseless. “You don’t need to torture civilians because you are overwhelmed. They [the SCAF] are a repressive force by nature and they require an authoritarian environment. After all, they were all appointed by Mubarak, served him well, and still represent this mind-set,” he told Salon.

"The days of blank checks are over"

Leahy’s bill would require the secretary of state to certify Egypt has held free elections and is promoting human rights and freedom of the press in order to transfer the $ 1.3 billion in aid. The liberal Democrat insists that establishing fundamental conditions for the aid is necessary to ensure the openness of the parliamentary elections and the long-term viability of Egypt’s democratic transition.

The unconditional approach has been tried. Over the last three decades, the United States has supplied over $60 billion in unconditional aid to the Egyptian military, even as the Mubarak regime rigged elections and trampled on human rights.

“Going forward, the days of blank checks are over, and it is in the mutual interest of the Egyptian people and the United States to reinforce these rights as conditions for our aid,” Leahy’s spokesman David Carle told Salon.

The State Department disagrees. A week after Leahy’s bill moved out of committee in late September, Secretary Clinton cautioned against altering the current aid scheme at a press conference here in Cairo: “We are against conditionality ... we will be working very hard with the Congress to convince [them] that that is not the best approach to take.”

As it became clear that the bill would make it to the floor, Assistant Secretary of State Andrew Shapiro (no relation to this reporter) ratcheted up the rhetoric. In a policy address earlier this month Shapiro warned that “conditioning assistance risks putting our relations with Egypt in a contentious place at the worst possible moment.”

The Obama administration’s case against conditioning aid is straightforward: In order to ensure U.S. influence in a post-Mubarak Egypt, the U.S. must pay to play. Placing conditions on aid would alienate the SCAF. Since February, the administration has preferred to rely upon behind-the-scenes pressure and gentle public prodding to cajole the SCAF into transferring power to a civilian government.

So far, this approach has failed spectacularly.

Egyptians head to the polls on Nov. 28, for the first round of a three-stage, four-month process of rolling votes across the country, which is slated to end in March. Meanwhile, the SCAF is maneuvering to ensure its supremacy over the incoming civilian government, which will be responsible for selecting a constitutional committee to draft a new Egyptian constitution.

On Nov. 1 , the SCAF-appointed Deputy Prime Minister Ali al-Selmi issued a set of principles designed to influence the constitutional drafting process before it even begins. The principles would insulate the Egyptian military from civilian oversight and could seriously undermine the incoming civilian parliament’s authority.

For example, Articles 9 and 10 of the constitutional principles declare the military the “protector of constitutional legitimacy” and mandate that the military budget be placed outside of civilian control.

These declarations drew widespread condemnation from across the political spectrum. The Muslim Brotherhood, whose Freedom and Justice Party stands to do quite well in parliamentary elections, has been especially critical of the move. Party president Mohammad Morsy threatened a “second revolution” if the principles are not withdrawn.

Outrage over the SCAF’s constitutional principles is a primary motivation for Friday’s protests and the Brotherhood is encouraging its vast constituency of supporters to voice their dissatisfaction in Tahrir Square.

Dr. Amr Derrag, the recently elected regional head of the Muslim Brotherhood party in the major metropolitan area of Giza, told Salon that he hopes the SCAF withdraws the principles before things get out of hand. Derrag said that the SCAF must resist the temptation to intervene in the civilian governing process. The “Turkish model,” in which the army reserves the right to overrule civilian governments, will not work in Egypt, he says. “If the constitution allows the army to intervene at any time this will be a disaster."

Since the SCAF has little interest in sharing power, its leaders seem to hope that this month’s elections will yield a divided and illegitimate parliament too weak to challenge its authority. It may very well get its wish. The elections will feature nearly 55 political parties, arranged in a dizzying and constantly changing constellation of alliances. There is little hope for transparency, since the SCAF has banned international election monitors (the Carter Center has been granted “witness” status) and many of the patronage systems that dominated Mubarak-era politics remain intact.

Local analysts are not optimistic. “What happens if, after the first round, the results and/or the tensions prompt a panicking military to cancel the poll?” writes Issandr El Amrani, a longtime Cairo-based journalist. “An already turbulent Egypt is entering a period of increased turbulence: Fasten your seat belts.”

Administration officials continue to praise the SCAF as a moderating force committed to democracy and there is a blanket refusal to even consider conditions on aid. But even some longtime supporters are rethinking that position.

Michele Dunne, a former State Department official, current director of the Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East, and one-time opponent of conditional aid, has penned a policy brief calling for just that.

“Egypt is at a critical moment right now," Dunne said in an interview, "and the United States should use all the leverage that it has ... if the [Egyptian] military undermines the political transition and the U.S. continues to supply military assistance, then we are complicit.”

Shares