The only connection most people have to Santería is Ricky Ricardo pounding on the conga drum in old "I Love Lucy" reruns. “Babalú, Babalú Ayé,” chants Cuban icon Desi Arnaz, bow tie loosened. Four decades after my first "Lucy" episode, I have learned that Babalú Ayé is the name of the West African orisha, or intermediary between God and man, that translates to “Father, lord of the earth.” Ayé is renowned for the control he exercises over disease and healing, and he is among the most powerful deities in the African and Caribbean spiritual traditions. Babalú is not just a nostalgic TVLand reference. He is an essential figure in Santería.

The only connection most people have to Santería is Ricky Ricardo pounding on the conga drum in old "I Love Lucy" reruns. “Babalú, Babalú Ayé,” chants Cuban icon Desi Arnaz, bow tie loosened. Four decades after my first "Lucy" episode, I have learned that Babalú Ayé is the name of the West African orisha, or intermediary between God and man, that translates to “Father, lord of the earth.” Ayé is renowned for the control he exercises over disease and healing, and he is among the most powerful deities in the African and Caribbean spiritual traditions. Babalú is not just a nostalgic TVLand reference. He is an essential figure in Santería.

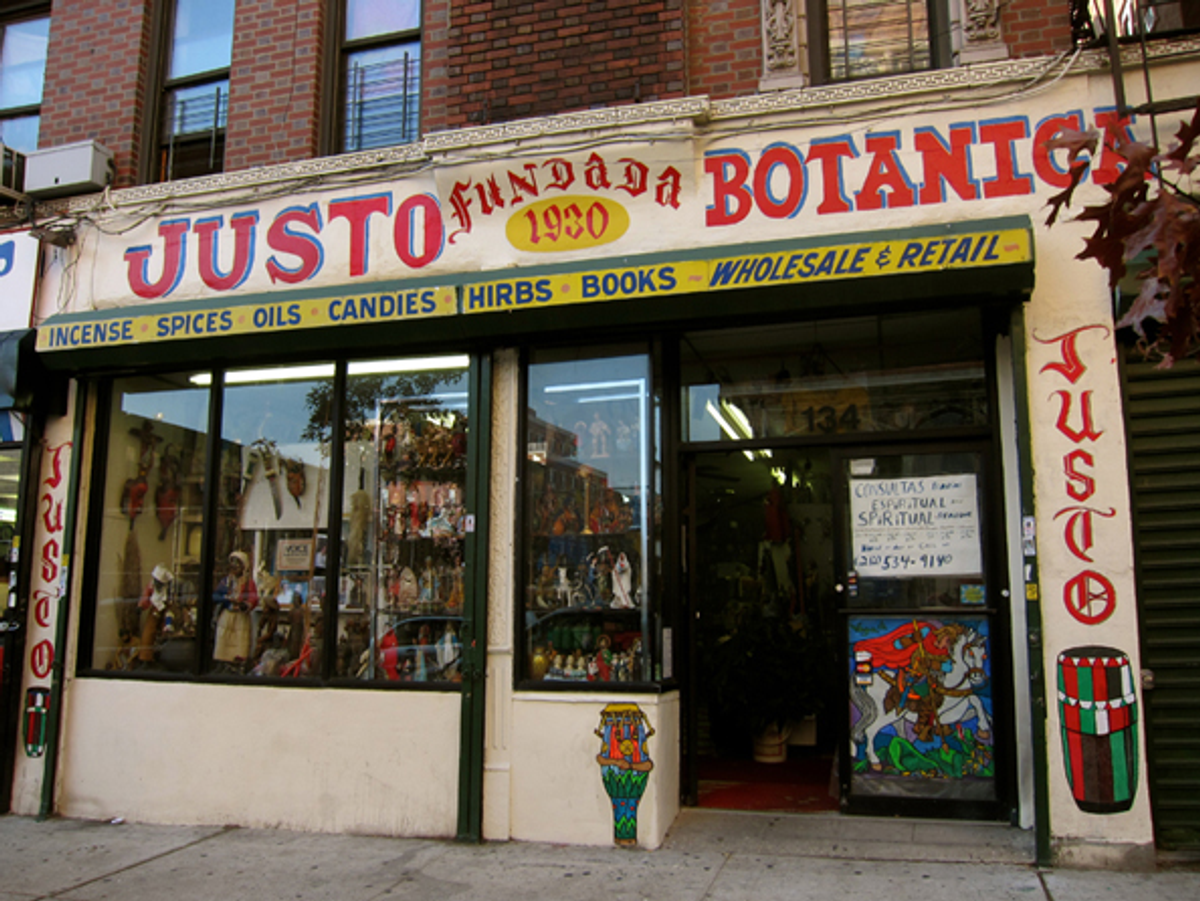

Santería is a belief system that blends the faiths of the African diaspora, Roman Catholicism and native Indian tradition. As African slaves were separated from their homelands and scattered through North America, they managed to retain aspects of their culture and traditions, and merged them with the belief systems of their new lands. The resulting faiths are still popular today, and widely practiced in Caribbean, African and Hispanic communities. The inexpensive fast luck candles found on the shelves of urban bodegas and grocery stores provide only a small glimpse into the world of contemporary folk and spiritual traditions. A visit to Justo Botánica on East 104th Street in New York City introduced me to a brand of faith based in part on spiritual products and their “alleged” mystical powers, as well as the wisdom and business savvy of their purveyors.

[caption id="attachment_229610" align="alignnone" width="460" caption="Justo Botánica on East 104th and Lexington, NYC"] [/caption]

[/caption]

A botánica is a retail store that sells products often regarded as magical or alternative. Botánicas carry the scented oils, sprays, candles and incense that are used in rituals (or in my case, displayed like trophies on my shelves). My mother tells the story of her middle-class upbringing in Kingston, Jamaica, in the 1940s, when she dismissed the suggestion of using herbs to rid her older brother, Sydney, of rheumatic fever. Frustrated that the family doctor was unable to cure him, their maid, a poor woman from the Jamaican countryside, plunged Sydney into a concoction of roots pulled from the backyard. She instructed him to soak in the “bush bath” regularly for seven days. Sydney and my mother, just teenagers at the time, mocked the rural folk medicine the maid conjured. But a week later, Sydney was cured. When I mention Justo Botánica and its myriad of remedies, my now-elderly mother, a devout Catholic, cautions me not to scoff.

[caption id="attachment_229613" align="alignleft" width="260" caption="My man Jorge"] [/caption]

[/caption]

Sixty-three-year-old Jorge Vargas is the owner of the cluttered Justo Botánica in Spanish Harlem, and he considers himself part pharmacist, part witch doctor. “I know my rituals,” Vargas says. “I can give an opinion. People come in for old-fashioned remedies.” Only minutes into my first visit to the shop, a customer asks for products to encourage hair growth. Vargas patiently pulls several items from the shelves behind the counter, and explains the sequence and number of days each product should be applied. But surprisingly, the majority of customers do not need instructions. “People come in and they know these things,” says Vargas. “They read and they buy.” While most arrive with shopping lists, they almost always look to Jorge Vargas for advice before final purchase.

“Tell the kids to pick five river rocks from the bottom of the water,” a young hospital worker in colorful scrubs instructs her husband by cellphone after a discussion with Vargas. “And can you get some water from the river and put it in a bottle?” The woman leaves with a small bag of carefully considered charms, and Vargas explains that customers create their own rituals. “People come in here in search of hope, as with any religion,” he says, and it’s his job to find or create the products that fit their specific needs. “People ask for things,” he continues, “and you remember the name and start making it.”

“You’ve got to be creative,” Vargas says. While suppliers from California to China provide materials to make some of Justo’s many ritual products, “It’s like the soaps you buy at the supermarket. The subtle differences make one product more desirable than another to a particular customer.” Varieties of soaps cover every need from the ubiquitous quest for romance to settling court cases. (Court-related products are particularly strong sellers.) “There are saints and rituals,” says Vargas, “incense, and of course, candles, which have always been popular. It’s called the Divine Light.” Black ritual candles are often used to subdue or destroy rivals and enemies, and are decorated with ominous skulls and blank spaces on which names of foes are to be inscribed. I purchase a black D.U.M.E. (“Death Unto My Enemies”) candle for fun, but am soon warned by my sister, a university professor, to dispose of it as quickly and as far from home as possible. I comply.

[caption id="attachment_229614" align="alignnone" width="460" caption="Candles manufactured by the Crusader Candle Co. in Brooklyn"] [/caption]

[/caption]

While I was initially dazzled by the array of colorful candles that line the back walls of Justo Botánica, it’s the quirky homemade ritual products that have piqued my curiosity over time. “You take what you know from different sources and combine it to create a new product,” Vargas says, somewhat cryptically. I wonder if the community Justo serves can afford to spend money on herbal remedies and lottery books ― is this stuff legit? Over the course of the winter, and through the spring, I pay Vargas sometimes-weekly visits; ironically, after my hour of psychotherapy only a few blocks away. I realize that it doesn’t really matter if Justo’s spiritual merchandise is real or not. Vargas’ words stick with me: “People come in here in search of hope.” As it turns out, I am searching for hope, too, and am unwilling to discount the power of faith in anything that brings even a small measure of peace.

[caption id="attachment_229616" align="alignnone" width="460" caption="I'll take two, please"] [/caption]

[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_229600" align="alignleft" width="163" caption="Enter at your own risk"] [/caption]

[/caption]

Floor washes, amulets and ritual baths are popular items at Justo, and the hand-crafted typography and line drawings on their packaging are both charming and true to the makeshift vibe of the shop. A recent computer-generated sign for spiritual readings is, thankfully, the only suggestion of digital technology to be found. And when Vargas proudly points it out to me, I ask for the old cardboard sign with its decorative yet earnest penmanship. I contact the new sign’s creator to make sure there are no future rebranding plans on the horizon. She is sweet and protective of Jorge Vargas, and while I don’t want to hurt her feelings, I find myself growing protective of him, too.

[caption id="attachment_229625" align="alignnone" width="460" caption="Some of Justo's homemade labels"] [/caption]

[/caption]

Vargas’ stepfather designed many of the original labels for items that are still produced by Justo, which first opened in the 1930s. Vargas continues to create packaging himself, using his own lettering, drawings, and photocopied engravings. He revels in the creative process and loses himself in designing Justo’s many bottle and jar labels. If a job is three colors, he redraws the art with the appropriate colored pens, and even has his own small press set up in the back of the shop to cut costs. Vargas still has original work created by his “daddy,” and pulls out a well-worn letter from 1945 requesting a copyright on a jinx removing alcohol. He becomes wistful as he recalls his father’s inability to secure the license. Vargas shows me tattered artwork for a poster of the seven orishas, a missed opportunity that he says his stepfather should have trademarked, along with many of the formulas and names of Justo’s ritual products.

[caption id="attachment_229630" align="alignnone" width="460" caption="Popular ritual baths"] [/caption]

[/caption]

As I poke Vargas with more questions about the creation of the packaging I’ve now grown to love and collect, he brushes off my curiosity with a smile. He tells me that it’s not about the design; it’s about the beliefs. What am I looking for? What keeps drawing me back to the sweetly scented shop with its statues, beads and talismans? There is something about Jorge Vargas that inspires trust. Members of the community clearly see him as part of their extended families. I drag my sister and teenage niece up to Justo, and Vargas is endeared by my sibling’s fluent Spanish. She notices a small group of women waiting for spiritual readings; a service Vargas provides in a back room, and asks them in Spanish for the price. We are taken aback by the high cost of enlightenment.

“I do tarot card readings spiritually with all my guidance and all my spirits,” says Vargas. “It’s something that’s gifted.” I return a few weeks later on a quiet Monday morning determined to get my cards read. I am in the back room I’ve wondered about, and have paid $45 for what I’m calling my experiment. I leave an hour later, more than a little spooked. I feel Vargas has peered into the depths of my soul. “My cards are like seeing a story about you,” he tells me as he studies the colorful, oversize tarot cards. “You are trying to make a decision on the path that you have taken,” he says slowly. “There are thorns that you are trying to pull out of your heart. You are seeing new things that you can hold. There are good things that you will receive in your soul. You have come to see the spirit of lights to see what they see in the crystal ball.”

[caption id="attachment_229634" align="alignnone" width="460" caption="SCORPION S"] [/caption]

[/caption]

My visits to Justo taper toward the end of the spring. Each time I stop by, Vargas asks how I am faring with the various issues we’d discussed during my reading, and says that we need to continue the conversation. I tell him that he’d actually freaked me out just a little, since he was talking about things that I knew I’d never mentioned before; topics that made my eyes well up with tears. He winks and tells me that’s his job.

[caption id="attachment_229631" align="alignnone" width="460" caption="Not developed by Jorge Vargas, but completely fascinating (soaps)"] [/caption]

[/caption]

I stop in again after being unexpectedly laid up in the hospital in May, and tell Vargas that I am a bit unnerved by the experience. He gives me a hug. I disappear again and return in the summer, the proud instructor with her class of eager tourist typography designers. Vargas regales them with the stories he’d shared with me that past winter. He is a gracious host, allowing the class to take pictures, and answers the same questions he’s probably answered every time a group of curious strangers stop in to buy a funny candle. My group is courteous, respectful, and appreciative. They purchase souvenirs. I am thrilled to expose the class to a little snippet of New York City culture that they may never have witnessed otherwise. And then I disappear for a few more months, still uneasy about Vargas’ ability to read not just my mind, but what is in my heart.

I make my way back to Justo in late October, keenly aware of my long absence, and am greeted like an old friend. It’s Saturday morning this time, just after a rescheduled therapy appointment, and I’m figuring it’s now been a year since my first visit to 104th Street. Vargas tells me I look “juicy,” which is probably a polite way of telling me I’ve gained weight, though he says it’s the Puerto Rican version of looking healthy.

[caption id="attachment_229619" align="alignnone" width="460" caption="Justo's version of Roman Catholic Holy Water"] [/caption]

[/caption]

I ask Jorge Vargas for advice on how to proceed in the coming months, though I’m sure I’ll stop by again before it gets too cold. I’m feeling a little more confident than I did when we first met, and certainly less lost than when I had my tarot cards read. Things are beginning to fall into place since I left my job suddenly late last fall, though the pace often feels glacial. “Well, my lady, you are researching,” Vargas says. “There’s a lot of good energy in what you’re writing. It is an energy that you will create into a book. Why? Because people are always seeking. If you write something, you will be of service. That’s your job. You have a life, but that’s up to you. If you stay in one position, you’ll get stuck. You have to find something you feel good with, or else you’ll just be by yourself with all your pressure. You have to make sure that you have your moment. But it’s up to you to make the move. If it goes sour, it doesn’t matter because you still got something out of it. You have to have an open mind.” Vargas kisses my hand and I leave Justo Botánica with two small bottles of Happiness Oil.

[caption id="attachment_229620" align="alignnone" width="460" caption="My new favorite thing ever"] [/caption]

[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_229629" align="alignnone" width="460" caption="Go away, evil!!"] [/caption]

[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_229627" align="alignnone" width="460" caption="Gotta love this..."] [/caption]

[/caption]

Copyright F+W Media Inc. 2011.

Salon is proud to feature content from Imprint, the fastest-growing design community on the web. Brought to you by Print magazine, America's oldest and most trusted design voice, Imprint features some of the biggest names in the industry covering visual culture from every angle. Imprint advances and expands the design conversation, providing fresh daily content to the community (and now to salon.com!), sparking conversation, competition, criticism, and passion among its members.

Shares