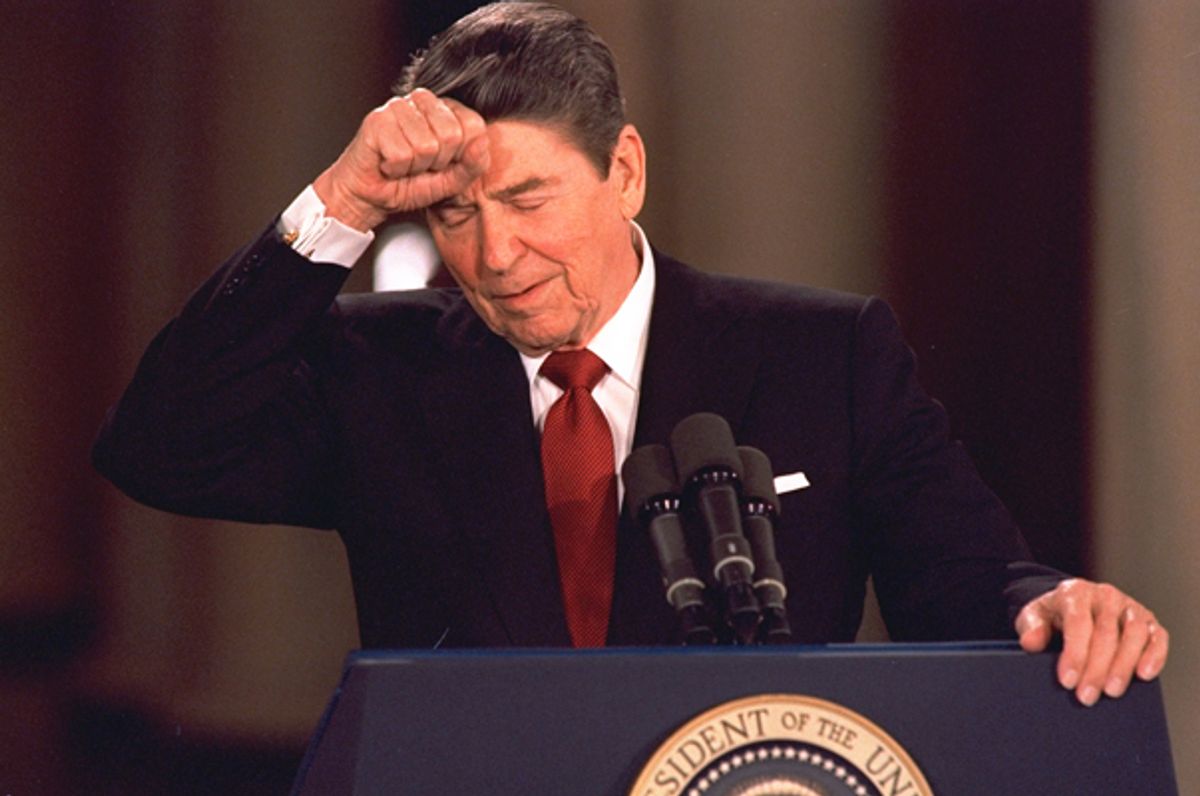

It has been 25 years since President Ronald Reagan stepped up to the microphone in the White House press room and made the announcement that launched one of the greatest scandals in modern American politics.

Reagan announced that his administration had sent “small amounts of defense weapons and spare parts to Iran” not to trade arms for hostages, but to improve relations and support moderate mullahs. There was “one aspect” of the operation that, the President said, he had been “unaware of.” His attorney general, Edwin Meese, then stepped forward to describe how “private benefactors” had transferred profits from those sales to counterrevolutionary forces, the contras, fighting to overthrow the Sandinista government in Nicaragua. No U.S. officials were involved, according to Meese, in this “diversion” of funds that linked two seemingly separate covert operations.

The focus on the diversion, as Oliver North, the NSC staffer who supervised the two operations wrote in his memoir, Under Fire, was itself a diversion. “This particular detail was so dramatic, so sexy, that it might actually—well divert public attention from other, even more important aspects of the story,” North noted, “such as what the President and his top advisors had known about and approved.”

The list of the “other… more important ” aspects of the sordid story that became known as "Iran-contra" scandal is a long one but worth recalling 25 years later. The Reagan administration had been negotiating with terrorists (despite Reagan’s repeated public position that he would “never” do so). There were illegal arms transfers to Iran, flagrant lying to Congress, soliciting third country funding to circumvent the Congressional ban on financing the contra war in Nicaragua, White House bribes to various generals in Honduras, illegal propaganda and psychological operations directed by the CIA against the U.S. press and public, collaboration with drug kingpins such as Panamanian strongman Manuel Noriega, and violating the checks and balances of the constitution.

“If ever the constitutional democracy of the United States is overthrow,” the leading political analyst of the scandal, Theodore Draper wrote at the time, “we now have a better idea of how this is likely to be done.”

Despite the gravity of the scandal, and the intense political and media focus it generated in the late 1980s and early 1990s, Iran-Contra has been largely forgotten.

Who remembers how many top NSC and CIA officials were convicted of crimes relating to the scandal? (Six, although two, Oliver North and John Poindexter, had their convictions dismissed and four were pardoned by President George Herbert Walker Bush.)

How many people would recall the televised Congressional hearings in 1987 that riveted the nation?

Who would be surprised to learn that a Congressman named Richard Cheney used his role as head of the minority side of the Congressional Iran-Contra investigating commission to develop his theory that the Executive has unilateral powers to do whatever the hell he wants?

Indeed, how many Americans are aware of the key roles played by President Ronald Reagan, and President-to-be George H.W. Bush?

Reagan and Bush were so deeply involved in various aspects of the Iran-Contra operations that the Independent Counsel, Lawrence Walsh, conducted a “criminal liability” evaluation on both of them. (My organization, the National Security Archive, recently obtained these records through the FOIA. We posted them on today.) The studies were drafted in March 1991 by a lawyer on Walsh’s staff, Christian J. Mixter, and represented preliminary conclusions on prosecuting both Reagan and Bush for various crimes ranging from conspiracy to perjury.

On Reagan, Mixter reported that he was “briefed in advance” on each of the illicit sales of missiles to Iran, even though Reagan had denied such knowledge at his November 25, 1986, press conference. The criminality of the arms sales to Iran “involves a number close legal calls,” Mixter concluded. He found that it would be difficult to prosecute Reagan for violating the Arms Export Control Act which mandates advising Congress about arms transfers through a third country—the first shipment of U.S. missiles were transferred to Iran from Israel—because Attorney General Meese had told the president the 1947 National Security Act could be invoked to supersede the Arms Export Control Act.

As the Iran operations went forward, Reagan’s top officials certainly believed that both the violation of the Arms Export Act as well as the failure to notify Congress of these covert operations were illegal--and prosecutable.

In a dramatic meeting on December 7, 1985, Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger told the President that “washing [the] transaction thru Israel would’t make it legal.” When Reagan responded that “he could answer charges of illegality but he couldn’t answer charge that ‘big strong President Reagan passed up a chance to free hostages,” Weinberger suggested they could all end up in jail. “Visiting hours are on Thursdays,” Weinberger stated.

On the contra operations, the “criminal liability” evaluation determined that the President had authorized the illegal operations by instructing his NSC aides to sustain the contras “body and soul” after Congress had terminated official assistance. But Reagan was not briefed on the details of the resupply efforts in sufficient detail that would allow him to be charged with conspiracy to violate the Boland Amendment—named for Massachusetts Congressman Edward Boland—that terminated aid to the contras in October 1984. Apparently soliciting the King of Saudi Arabia to cough up millions of dollars to replace Congressional funds was not a prosecutable crime either.

On the role of George Herbert Walker Bush, Mixter reported that the Vice President’s “knowledge of the Iran Initiative appears generally to have been coterminous with that of President Reagan.” Indeed, on the Iran-Contra operations overall, “it is quite clear that Mr. Bush attended most (although not quite all) of the key briefings and meetings in which Mr. Reagan participated, and therefore can be presumed to have known many of the Iran/Contra facts that the former President knew.”

The first President Bush had publicly portrayed himself as “out-of-the-loop” on both the Iran and Contra operations—and indeed had fostered that image of innocence throughout the 1988 presidential campaign. The 89-page Mixter report is nothing less than a chronicle of mendacity on Bush’s part. The report reveals for the first time that in 1983, Bush chaired a secret “Special Situation Group” that had “recommended specific covert operations” including “the mining of Nicaragua’s rivers and harbors.” Between 1984 and 1986, he attended no less than a dozen meetings at which illicit assistance to the contras was discussed.

But since Bush was subordinate to Reagan and was implementing his policy, his role as a “secondary officer” rendered him not criminally liable for these surreptitious operations.

Despite the Mixter evaluation, Independent Counsel Lawrence Walsh considered criminal indictments against both Reagan and Bush. In a final effort to determine Reagan’s criminal liability and give him “one last chance to tell the truth,” Walsh traveled to Los Angeles to depose the former president in July 1992. “He was cordial and offered everybody licorice jelly beans but he remembered almost nothing,” Walsh wrote in his memoir, Firewall, The Iran-Contra Conspiracy and Cover-Up. The former president was “disabled,” and already showing clear signs of Alzeimers disease. “By the time the meeting had ended,” Walsh remembered, “it was as obvious to the former president’s counsel as it was to us that we were not going to prosecute Reagan.”

The Independent Counsel also seriously considered indicting Bush for covering up his relevant diaries that Walsh had requested in 1987. Only in December 1992, after he had lost the election to Bill Clinton, did Bush turn over the transcribed diaries. During the independent counsel’s investigation of why the diaries had not been turned over sooner, Lee Liberman, an associate counsel in the White House counsel’s office, was deposed. In the deposition, Liberman stated that one of the reasons the diaries were withheld until after the election was that “it would have been impossible to deal with in the election campaign because of all the political ramifications, especially since the President’s polling numbers were low.”

In 1993, Walsh advised now former President Bush that the Independent Counsel’s office wanted to take his deposition on Iran-Contra. But Bush essentially refused. In one of his last acts as Independent Counsel, Walsh considered taking the cover up case against Bush to a Grand Jury to obtain a subpoena to force a deposition. On the advice of his staff, he decided not to pursue an indictment of Bush.

Both Reagan and Bush got away with their misconduct in the Iran-Contra operations. Few reviews of Reagan’s legacy even include mention of the scandal; Bush’s son was elected and re-elected president, bringing Richard Cheney with him-into the oval office. For Cheney, the lessons of the scandal were that the White House had the prerogative to ignore the law and the constitution in its exercise of power. We are still living with the consequences of that approach.

“The Iran-Contra affairs are not a warning for our days alone,” Draper presciently wrote at the time. “If the story of the affairs is not fully known and understood, a similar usurpation of power by a small strategically placed group within the government may well reoccur before we are prepared to recognize what is happening.”

Twenty-five years later, that is why we remember the real meaning of the scandal that defined the dangerous abuse of presidential power.

Shares