On Friday, Philadelphia Mayor Michael Nutter made the long-expected announcement that Occupy Philly had 48 hours to abandon its month-long encampment outside of Philadelphia's city hall, where a major construction project is expected to begin soon. Come Sunday night, the mayor let the deadline pass without incident. While the occupiers defiantly repacked Dilworth Plaza preparing to be arrested there, many participants and leaders of the movement also acknowledge that its expected eviction comes as a mixed blessing.

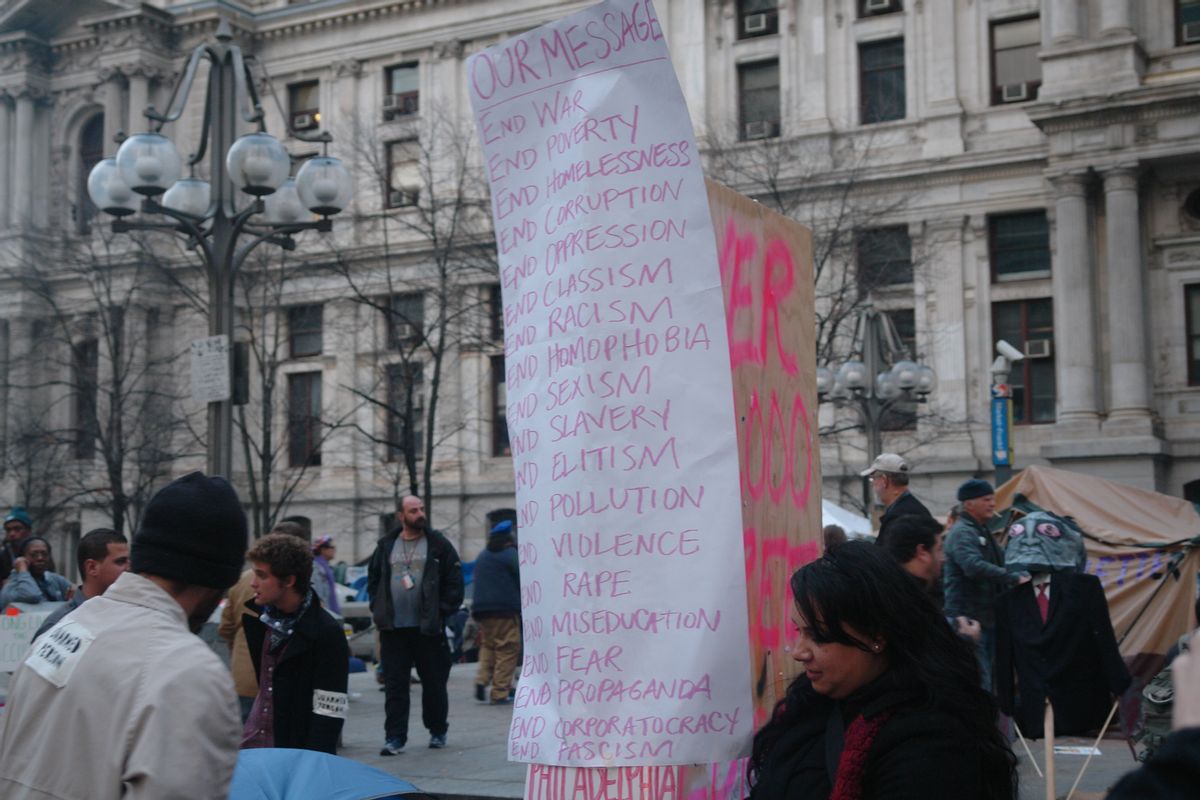

Occupy Wall Street, as the movement began in New York, proliferated, and ― for a spell, anyway ― thrived as a taking of public space, which spoke at least as loudly as any particular message. But occupation in troubled urban spaces can also be a liability. Whether the movement can or should continue to focus on occupying public places ― in winter, no less ― is a question these movements are now grappling with around the country.

Even before Nutter announced the imminent crackdown, a sense that Occupy Philly itself had gone awry was becoming more and more evident. When I went to visit on Wednesday night ― the night, that is, before Thanksgiving, when even the more radical are called to family dinners ― I found less of an occupation than a ghost town.

Gone were the drum circles, the frenzy of activity, and many of the trappings of the larger project that had started there: the media tent, I was told, had been dismantled after it became a destination for drug use. The Occupy Philly “library,” once a proud symbol of the movement's defiant energy, had been reduced to a few soggy books lying on a few soggy shelves. Here and there around the camp were small pockets of people ― many, if not most, members of the camp's ever-growing homeless population ― who seemed preoccupied with their own affairs.

And where an influx of the homeless posed problems for the occupiers of Zuccotti Park in New York, it had come to dominate Occupy Philly.

“We were a magnet ― for the angry poor, the homeless, the angry poor drunks,” acknowledged Ariel Friedman, a young man quietly hunkered down that night by the defunct library. “And as the number of people here to absorb that part of it got smaller, it just became overwhelming.”

“There was fighting, you know? You put all these people together and there were a mess of fights,” attests Greg Luce, a 54-year-old Merchant Marine and Quaker activist who hadn't been back to his New Jersey apartment in a month and who had taken on the role of monitoring nighttime safety.

“We tried ― we tried. We see somebody sleeping, we throw a blanket over them, you know ― but there are people here who really need help.”

The thing is, it's not just that Luce is sympathetic to the plight of the homeless who've filled the plaza ― for him, it's become a concern that trumps whatever Occupy winds up doing: “I don't think it really matters either way,” whether Occupy Philly maintains a physical presence anymore, he said. “But these people are scared; when the party's over, what are they going to do?”

And even as the occupied space became a magnet for a host of problems occupiers weren't necessarily ready for, it also became the heart of strife with the city and within the movement itself. When debate over whether and how to move the encampment dragged on in the group's general assembly, a dissenting group split off to form its own faction, “Reasonable Solutions,” which began to meet with the city ― and eventually apply for a permit ― on its own. On Friday, the mayor granted access to a site across the street to Reasonable Solutions, the faction ― and not Occupy Philly, which applied for its own permit ― adding that he intended to find the rebel dissenting group (not Occupy Philly) office space.

Meanwhile, as the camp outside City Hall faces more or less certain demise, those most involved with the project this whole time are contemplating what might be next ― and they sound optimistic.

“I do think the physical occupation was sort of the galvanizing point,” concedes Dave Marley, a 20-something musician who's been helping facilitate most of the group's meetings. “But, forward, I don't know that a physical occupation is necessary to sustain or build the movement.”

Maybe he's right. Occupy Philly members are already moving on. A plan is in the works to “re-occupy” a house from which a poor African-American woman, who came to a recent general assembly meeting, was evicted along with her kids. Other Occupy spinoff movements are underway: When I called Khadija White, a graduate student and member of Occupy Philly's People of Color working group, she hadn't even heard about the mayor's 48-hour warning ― she was too busy planning a campaign against the mayor's recent push for stricter youth curfew laws.

“Is Dilworth Plaza important to this?" she said upon hearing news of the impending eviction. "I think it is ― it creates a space for people to come together and learn and really engage. But it's winter on the East Coast. We need to think of the safety of everyone. And we're not going anywhere.”

The first test of the Occupy movement was whether it would sustain itself and grow beyond the excitement of its first few days and first major confrontation with law enforcement and whether it could get people to pay attention to it: It passed. The second test was whether a ragtag bunch of protesters could do what American society couldn't: live in peace, feed the hungry, shelter the homeless. It failed in that, but there's maybe an argument to be made that if it failed, it failed nobly, doing no worse than than America, with all its means, has done.

This is its third test: surviving as a movement without the spectacle that kept the media coming back and the sheer exuberance that turned who knows how many people into activists overnight.

Following the rapid eviction of Zuccotti Park in New York, Occupy activists staged huge protests around the city ― but then went all but silent over the ensuing week, staging only a rather muted protest of American consumerism on Black Friday. Occupy Philly may very well fall into a similar lull in the coming weeks or month. Whether the movement is faltering ― or just hibernating ― remains to be seen.

But don't write it off too early. Even occupiers who expressed to me outright disillusionment ― Ariel Friedman, squatting by Occupy Philly's own shuttered library comes to mind ― didn't seem lacking in spirit. For all the failures of the encampment, Friedman had told me, he was proud of it, and he was staying until the bitter end.

“Somebody's gotta be here,” he said, “keep an eye on things through the winter.”

Shares