"The Zuccotti virus has spread," announced one of the giant canvas banners hanging from the New School Study Center on New York's Fifth Avenue. The Wells Fargo-owned building in Manhattan was occupied for almost two weeks in November, and it announced a new phase for Occupy Wall Street.

While there has been much speculation about what Occupiers would do once they were evicted from outdoor encampments or when the winter chill rendered park-based occupations untenable, for many, the next step is obvious. Protesters have begun to creep -- and sometimes storm -- indoors, with actions that both highlight the abundance of foreclosed buildings and challenge assumptions about private property.

“As we are continually and violently pushed out of public spaces, the people of this city must find new spaces in which to foster dialogue, learn and engage politically. Private spaces must be liberated; the movement must expand,” reads a communiqué released from the occupation at 90 Fifth Avenue, which Occupiers abandoned last week to evade forcible eviction.

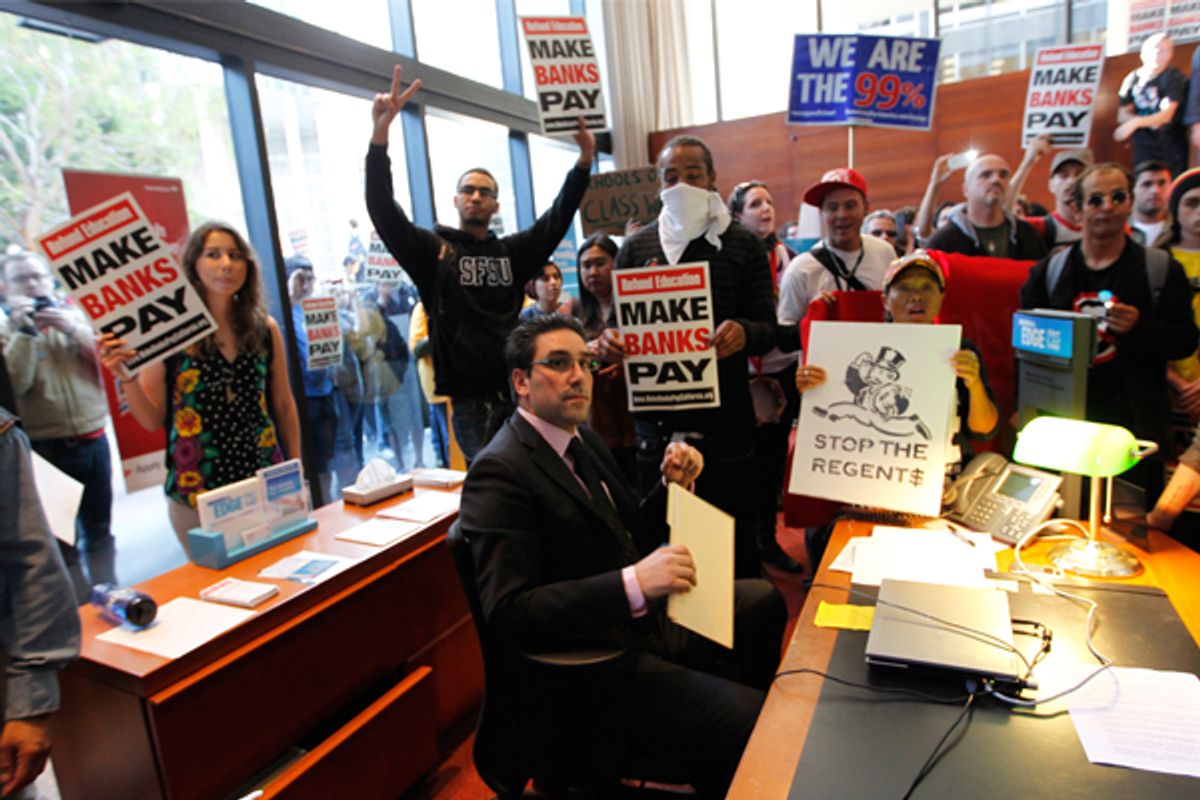

Indoor occupations are becoming increasingly commonplace for OWS supporters nationwide. This month, an estimated 100 protesters swarmed into the lobby of a Bank of America branch in San Francisco’s financial district. They danced on desktops and erected a tent in the name of Occupy San Francisco. The building was cleared of protesters hours later, with 95 arrests reported. In Washington, D.C., police arrested 13 Occupiers who briefly took over an historic school-turned-homeless-shelter, which was shuttered in 2008. Over 200 Occupy D.C. supporters gathered outside the vacant, city-owned building in a failed attempt to defend it.

Mike Andrews, 30, a New York-based writer and editor who has participated in Occupy Wall Street since before the occupation of Zuccotti Park began in September, said that whispers about “re-appropriating” buildings had been echoing around the encampment for some weeks.

“As the weather got colder, there were fewer rumors about expanding to a new park and more about trying to move indoors, especially looking to foreclosed properties or buildings that once provided public services but were shut down because of budget cuts,” said Andrews.

“My view,” he added, “is that there will be a lot of thwarted attempts to take buildings before any successful, long-term indoor occupations.”

Indeed most OWS incursions into buildings have already been shut down swiftly as police departments across the country make clear that infiltrations into private property (vacant or otherwise) will be met with the full force of the law. On the now-infamous night of November 2, when a call for a general strike in Oakland drew a crowd of over 10,000 to the city’s port, a couple of hundred Occupy participants took over an unused building. According to a statement from the Occupiers, it “formerly housed the Traveler’s Aid Society, a not-for-profit organization that provided services to the homeless but, due to cuts in government funding, lost its lease.” Before the sun rose, hundreds of police armed with tear gas, beanbag guns and flash-bang grenades cleared the building of protesters.

And in an incident that soon came to exemplify the harsh police crackdowns occupiers have met, a SWAT team armed with live-ammo semi-automatic rifles stormed a building that had been occupied for one night in Chapel Hill, N.C.

“A group of anarchists wanted to make the building into a community center. They believed they had the right to repurpose the vacant building, because the owner had done nothing with it since he bought it in 2004,” said Josh Davis, a graduate student at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill and a freelance reporter. Davis was briefly detained by heavily armed officers while reporting on the eviction of the building, which had been a Chrysler dealership until it closed in 2003.

Occupy protesters are by no means the first groups to attempt to reclaim vacant spaces across the United States in recent years. Writing for Salon in May 2010, I noted that squatters and homelessness advocacy groups saw opportunity in the tens of thousands of foreclosed homes and abandoned construction sites, which sat vacant and speculated upon by real estate companies and banks in the wake of the financial crisis.

At the time, Tom Angotti, a professor at Hunter College's department of urban affairs and planning told me, “Everybody knows there’s a lot of potential for squatting now… but the type of vacancies that there are today are very different to those that arose in the 1980s. A lot of them are due to unfinished construction, and will be occupied again when the economy picks up.”

The economy remains distressed, but Angotti’s prediction – that vacant buildings will again be “occupied” – has new meaning in light of Occupy Wall Street. Unlike in 2010, thousands of people this year have shown themselves willing to mobilize and risk arrest in the name of occupation. Across the Atlantic, recent indoor occupations are also proving robust. Activists seized an entire vacant, UBS-owned office block in London in mid-November and have repurposed it for public use and community services. The entire complex remains in occupiers’ hands and now goes by the name “The Bank of Ideas.”

“The zeitgeist is particularly favorable now; occupation is the word of the moment,” said Frank Morales, a mainstay of the 1980s Lower East Side squatters movement in New York. He served many years as the assistant pastor at St. Mark’s Church and has recently been working with Organizing for Occupation – a direct action group which helps move homeless people in vacant buildings and orchestrates foreclosure eviction defenses.

Morales said that most OWS participants who have approached him recently for advice on seeking indoor spaces to squat in New York have sought big spaces, where community services could be set up and general assemblies and working groups could meet. “In the last instance, people are seeking permanent living spaces for themselves or for people without housing,” Morales said.

Occupy protests in New York, Minnesota, San Francisco, Atlanta and others have also mobilized to defend homes from foreclosure by gathering large crowds to stand in front of houses when eviction threatens, or by simply threatening to mobilize -- leveraging the Occupy protests’ popularity to force banks and speculators to negotiate with troubled home owners.

And despite focusing on foreclosure defenses and housing the homeless himself, Morales praised the variety of indoor squat and occupations that people are attempting to take and hold, adding, “property is a terrain of conflict, and people stepping into it in a forbidden way. They’re deciding they’ve had enough. Squatting is a practical way of exhibiting this self expression.”

Like the actions in the streets, parks and plazas that have constituted OWS, the building occupations have not been uniform in either purpose or method. Also like the park and plaza occupations, the indoor actions have challenged notions of public and private space and how it is used. What was once a concrete park in lower Manhattan, which hosted business people on their lunch breaks, became a tent city and site of political interaction and conflict with authority. A once-quiet New York student center hosted 24-hour anti-capitalist film screenings, General Assemblies, dance parties, dinners and squatters without a university affiliation.

Early in the Zuccotti Park occupation, a flyer from the Barcelona occupation, translated into English, spread amongst marchers. It proclaimed that “The greatest violence would be returning to normality” and concluded “We don’t just want the plaza; we want the whole city." As more and more attempts to take buildings and indoor spaces are made across the United States, perhaps the Occupy movement's winter strategy was hiding in public all along.

Shares