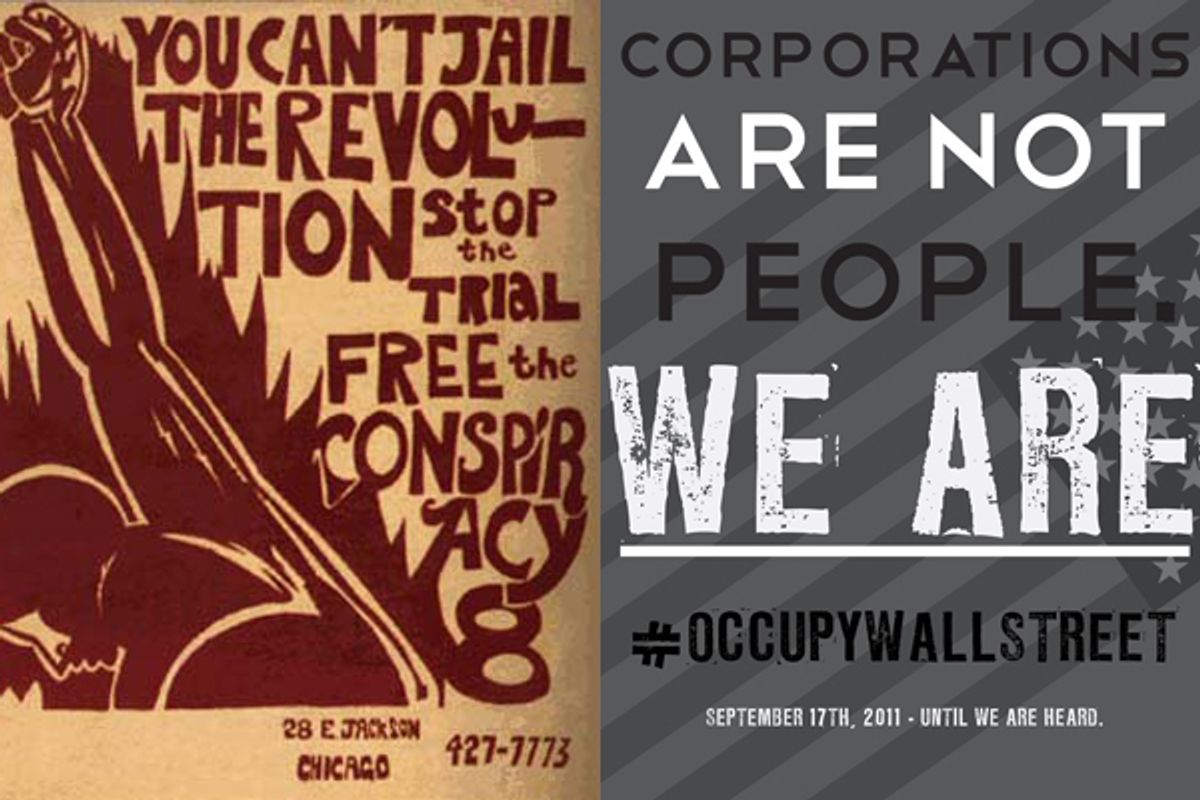

Conventional wisdom guru John Heileman suggested yesterday in New York magazine that the next phase of the Occupy Wall Street movement might be “about, in effect, transforming 2012 into 1968 redux.” Although Heileman found, depressingly, that many of the young activists were “surprised” when he pointed out that “the demonstrations in Chicago in 1968 occurred at the Democratic, not Republican, convention, and helped to shatter [Democratic presidential candidate Hubert] Humphrey’s base,” their ignorance of the possible consequences of their course does not lessen the seriousness of the threat they pose. If 2012 is another 1968, President Obama is in trouble.

Heileman’s piece chillingly highlights the Obama campaign’s cavalier attitude toward the young activists.

David Plouffe, his campaign manager in 2008 and now a senior adviser in the White House, had told the Washington Post that the Obamans intended to make the public ire at Wall Street crystallized by OWS ‘one of the central elements of the campaign next year.'

A few days after Plouffe’s pronouncement, the president made his famous empathy move: “I understand the frustrations being expressed in those [OWS] protests.” Apparently Chief of Staff Bill Daley did not get the memo, because he said in an interview that he didn’t know if OWS was helpful. In commenting on Daley's pronouncement, Todd Gitlin, a historian and a radical in 1968, told Heileman, “Sometimes these things blow up and leave everything in ruins.”

Heileman's point is that the dynamic between the Obama campaign and the occupation movement is going to be a bigger factor in next year's presidential campaign than most people know. Obama’s approaches haven't been all that successful. Iowa OWS activists ungratefully dismissed Obama’s sympathy, expressing a preference that their president change what he’s doing rather than sympathize with them for resisting it.

Such attitudes are endemic among the occupiers. One of the elusive non-leader leaders Heileman interviewed picked it right up: “These [protesters] aren’t out here because they’re offended that they haven’t been spoken to nicely. They’re out here because they owe shitloads of money in student-loan debt and can’t find a job. Or they can’t afford their mortgage. And if Obama thinks that they’re gonna be able to divert this energy by talking about doing something, he’s got another thing coming.”

Obama’s best hope is that Occupy Wall Street either dies of Sudden Infant Movement Death Syndrome or grows up really fast. The former seems more likely. The occupation is vulnerable to all kinds of fatal baby movement diseases; it may be unable to focus its energy long enough to survive, or it may be paralyzed by procedural purity. Movements with no formal structure for selecting leaders tend to throw up leaders anyway; as one of the activists noted, some people just have more leadership capacity than others do. But the lack of legitimate selection avenues usually results in serial leadership decapitation, as the less gifted rebel against their lesser fates by bringing down the greater. Think Radicalesbians or Gay Liberation Front. Neither lasted more than a few months.

Less probably, OWS may make a punctuated evolution to a movement that can do business with the Democratic Party, or split into a movement that leaves the irredentists behind. Signs of that development may surface as soon as the Iowa caucuses in January. If the occupation movement can elect sympathetic representatives to start up the food chain to become delegates to the Democratic convention, or to engage in conversations with the people who will be drafting the party platform. The labor unions and groups like Moveon.org, who occupy the middle ground between the leaderless civil society and the tidy Obama reelection organization, would be the obvious ones to broker a deal. The resulting coalition could just bring enough populist energy to the Democratic Party cause to avoid a replay of the defeat that Humphrey suffered in 1968.

Ironically, the immature but powerful occupation movement is Obama’s baby. As another occupation non-leader, Yotam Marom, told Heileman, “Obama didn’t build a movement, he built an electoral machine. If he had built a movement, he would not be where he is right now. But the fact that he was elected, that so many people came out in the streets for him, that people cried when he won, was an expression of the fact that they wanted what they thought he was, which is an alternative. He wasn’t it.”

Thus the occupation movement echoes the plaintive cry of the student movement of the 1960s, as articulated by sociologist Kai Erikson: “Don’t shoot: We are your children.”

Will 2012 be a replay of 1968? While Heileman highlights the question, he is too shrewd to risk a definitive affirmative answer, observing merely that the occupation movement “might alter the landscape the president must traverse next year in dramatic and unpredictable ways.”

Meaning: Then again it might not.

I’m predicting that it will. Here’s why. It doesn’t take much to make a media melee. There were no more than 10,000 demonstrators in Grant Park on that fateful August night in 1968 when a police riot resulted in widespread brutality that discredited the Democratic Party in the eyes of the young and linked it to chaos in the eyes of many others.

Occupy Wall Street has already shown it can draw a crowd that large. The occupiers will come to Charlotte, N.C., because it's the Democratic Convention. The wild card is, as it always is for social movements, the willingness to deal and receive violence. By the time the antiwar protesters gathered in Grant Park in Chicago, they had already had several rounds of violent confrontation with the police at other protests.

The occupation movement has endured and survived a bout of police action but has not (with the possible exception of Occupy Oakland) been willing to push back hard, at least not yet. But, as the eviction from Zuccotti Park showed, social movements that threaten the status quo can usually count on the police to raise the violence level for them. And even if there is no exact replay of 1968, the mere possibility should be exerting a pull on how presidential politics is played over the next several months. The really interesting question is not whether the occupation movement poses a 1968-style threat to the reelection of Barack Obama. The interesting question is why his people are so dreamily oblivious about it.

Shares