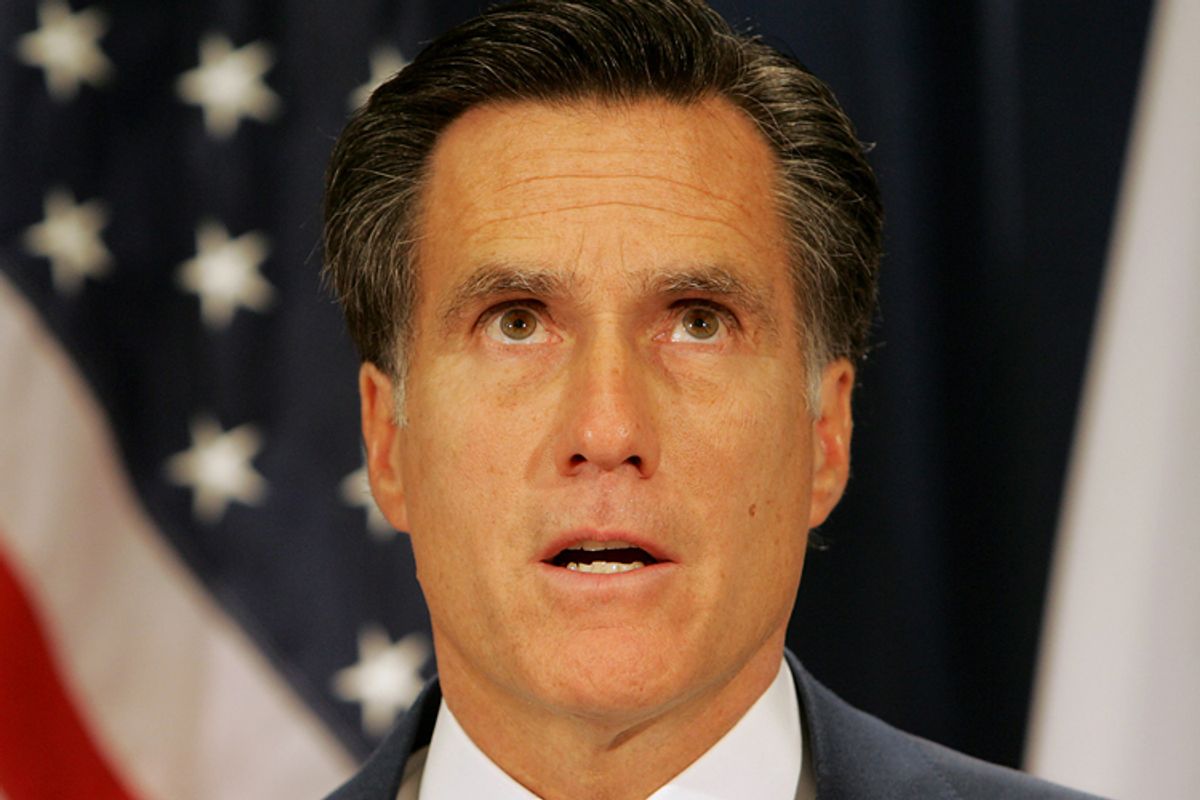

When it comes to deep erosion of support, Mitt Romney is no political newbie. His collapsing poll numbers as governor of Massachusetts (from 2003 to 2007) are an ominous preview of the steady disenchantment he is experiencing now.

“His favorability was basically a straight line down from his honeymoon,” said David Paleologos, director of Suffolk University’s Political Research Center and a longtime Massachusetts pollster. “Sometimes familiarity breeds contempt.”

Now a University of Massachusetts-Lowell/Boston Herald poll conducted last week shows that 48 percent of registered voters in Massachusetts have an unfavorable opinion of the former Republican governor, compared with just 40 percent favorable. In September, 45 percent of voters thought favorably of Romney, while 43 percent looked unfavorably on him. This 10-point swing in his favorability rating is mirrored nationally and in polls in early-voting states. For Romney, rapid descent is a familiar feeling.

Let’s go to the videotape.

Romney entered the Massachusetts State House in January 2003 with a flashy favorability rating of 61 percent. After demanding cuts to fix a $650 million budget hole, voters rewarded him in March 2003 with a 61 percent job approval rating as well, according to a University of Massachusetts-Lowell poll.

That was Romney’s zenith. By November 2004, voters were souring, and a Suffolk poll found his favorable rating had dropped to 47 percent.

A year later, that rating sank another 14 points. Just 33 percent of Bay State voters had a favorable opinion of Romney in 2005, according to Suffolk, while 49 percent were unfavorable.

Things did not improve in 2006, when Suffolk found that his unfavorable rating had risen to 55 percent while his favorable remained stagnant.

By November 2006, as he closed out his increasingly absentee term, his overall job approval rating had cratered to 36 percent. He’d also begun ducking reporters, notably dodging questions after a menorah-lighting ceremony outside his office.

“To know Mitt Romney is to dislike him,” said Thomas Whalen, a Boston University political science professor. “That is the moral of the story.”

The Hanukah episode came after Romney spent nearly a month away from the Bay State – and the local media -- stoking his 2008 presidential ambitions. After cheerfully delivering remarks to a Jewish audience about a neighbor whose name wasn’t Semitic-sounding, Romney dashed down the hall to his office as reporters gave chase. It was not endearing.

Romney was hurt by a slow economic recovery -- while the jobless rate fell, the state was 47thin the nation in job creation, according to the Center for Labor Market Studies. He also raised $375 million of business taxes, according to the Massachusetts Taxpayers Foundation. Being a Republican in Massachusetts during the Bush administration hardly helped.

But Romney’s laser focus on his presidential aspirations led to a political blunder that cost him dearly. He wagered his future on running a slate of 100 Republicans against a Democratic state Legislature in 2004 in a very blue state – and they all lost. Romney, Whalen said, spent the rest of his term using his post as a springboard for his next gig – the presidency.

“It was so blatantly obvious he was planning to leave town,” Whalen said. “People saw it as a cynical ploy.”

A week of polling now shows that Romney is dropping in early-voting states. The more he campaigns, the more ground he seems to lose.

Perhaps most worrisome is word that Romney’s lead in New Hampshire has dwindled. It’s currently 39 percent, versus 23 percent for sudden front-runner Newt Gingrich. But Romney once polled at 45 percent in New Hampshire, a state that knows him almost as well as Massachusetts does.

"Romney has a coldness, an aloofness about him. It's hard to warm up to him,” said University of Virginia political scientist Larry Sabato. “That's the reason he doesn't wear well. He aims to please constantly, he desperately tries to please, but he doesn't."

Sabato reckons the problem is all in Mitt’s head.

“There’s a rigidity in Mitt Romney, in his personal and private life,” Sabato said. “He puts a plan together and follows it even when it’s not relevant to new developments. And that’s one of the problems.”

To Whalen, Romney’s history of wearing thin on voters and his rough relationship with the press shed critical light on the Mitt meltdown on Fox News, and his reaction to the sudden ascent of Gingrich. His problem isn't a new rival. His problem is himself.

“Romney is showing all the opposite traits [of Gingrich], showing bizarre behavior with the press and voters,” Whalen said. “He’s treating this as a coronation when it’s far from a lock."

Here’s the kicker: We asked the Romney camp multiple times over two days to explain the drop in the polls, but they did not respond.

Shares