All month, the critics will have their say on 2011's best books. Our Laura Miller selected her top fiction and nonfiction earlier this week.

But every year we also poll some of our favorite writers of the year and ask them to play critic. They have to answer the simple but agonizing question: What was the best book published this year?

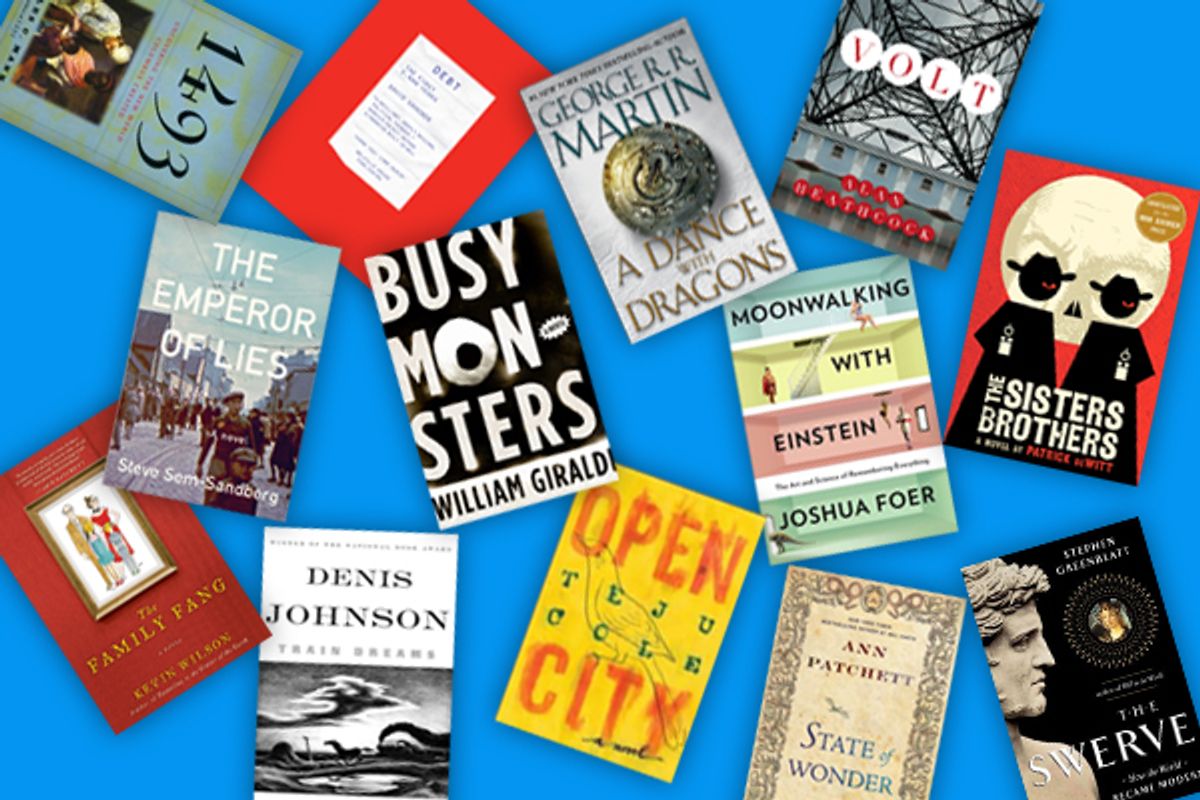

The more than 50 responses we received -- from Pulitzer Prize and National Book Award winners as well as big-time bestsellers -- chronicle a thriving, eventful year in the life of the literary culture, and will likely point you toward more than a few titles you haven't read (or maybe haven't even heard of). Some of the most popular selections on our list haven't shown up on many others, including Denis Johnson's "Train Dreams" and Alan Heathcock's story collection "Volt." (Another book popular with critics, Chad Harbach's "The Art of Fielding," was surprising in its absence here.)

But whether it's the reissue of an obscure Hungarian tale (recommended by Arthur Phillips) or one of the year's major, blockbuster releases (e.g. George R.R. Martin's "A Dance With Dragons"), we hope you'll find something here to enjoy over the holidays and through the coming year.

Jeffrey Eugenides, author of "The Marriage Plot" (FSG)

"The Empty Family," by Colm Toibin (Scribner)

My favorite book of 2011 is Colm Toibin's latest collection of stories, "The Empty Family." I attended a reading of Toibin's in Princeton, and when I mentioned that I was going to give the stories to my mother, he warned me not to: too much explicit gay sex, apparently. Well, that's true about a couple of stories here, but I think my mother could have handled it, if only because she's a good reader, knows what art is, and would have enjoyed the range of subjects and lives treated here. Toibin doesn't make the mistake of yoking his groundbreaking material to an outlandish style. He works in a more traditional Irish mode, or traditional-seeming, so that what you get is the best of both worlds: the embrace of an old-fashioned storyteller telling the newest of tales.

Arthur Phillips, author of "The Tragedy of Arthur" (Random House)

[caption id="attachment_10303985" align="alignleft" width="186" caption=" "] [/caption]

[/caption]

"The Adventures of Sindbad," by Gyula Krúdy (New York Review Books)

Krúdy is the best writer you've never heard of. A Hungarian who hit his peak in the 1920s and '30s, he is unique. He just is. There's really no one to compare him to that gets you any closer to what he does well. I can tell you that if you like Proust, Kafka or Schnitzler, you'll feel at home with Krúdy, but that doesn't quite capture it. Come for the atmosphere, the Central European mist, the fin-de-siècle eroticism and above all, the bursts of language. Don't come for the plot. Don't expect to hurry through it and devour it for a quick story. Pour yourself a glass of Tokaj, dim the lamps, turn off your electronics and prepare to experience something new. (It just happens to be 90 years old.)

Ann Patchett, author of "State of Wonder" (HarperCollins)

[caption id="attachment_10303986" align="alignleft" width="186" caption=" "] [/caption]

[/caption]

"The Family Fang," by Kevin Wilson (Ecco)

This book was my favorite for the sheer force of its creativity. Mr. and Mrs. Fang are performance artists whose art consists of public disturbances, usually centered around their children, Annie and Buster. As Annie and Buster grow up they have to deal with the repercussions of their crazed family and figure out the relationship between art and life. This book is powerful, funny and deeply strange. You won’t read anything else like it.

Sebastian Barry, author of "On Canaan's Side" (Viking Adult)

"The Emperor of Lies," by Steve Sem-Sandberg (FSG)

Steve Sem-Sandberg's resolute masterpiece "The Emperor of Lies" looks for truths in the great domain of dissolving syntax and shadows we call history, in this case the Polish ghetto of Lodz, and the hugely ambiguous, maybe finally unknowable figure of Mordechai Chaim Rumkowski, the supposed leader/"chairman" of the ghetto. Sem-Sandberg's method is an infinitely patient unspooling of a story that threatens storm everywhere, storm, and great sadness, and great suffering. The old ghettos may be gone, and the roads not lead there anymore, but it is one of the strange graces of fiction that a road of fire may be built back into time, and into razed and ruined places ... Sem-Sandberg weighs the ideas of goodness and rightness against the heavy ashes of those things. A harrowing but a great achievement.

Jesmyn Ward, author of "Salvage the Bones" (Bloomsbury)

[caption id="attachment_10303988" align="alignleft" width="186" caption=" "] [/caption]

[/caption]

"Power Ballads," by Will Boast (University of Iowa Press)

Will Boast’s story collection, "Power Ballads," works as beautifully as a good album. From the first page, this book transports the reader into a collection of linked stories that are not bound by reoccurring characters (well, not mostly), but by music. The characters in this collection live for rhythm, are aspiring musicians or failed musicians or successful musicians, and the joy and pain of music resounds through every word. We meet a young polka prodigy, a former jobber, an artist on the rise, among others, and each character’s story is so essential, so alive, so immediate. With a line, an image, Boast’s prose acts like a long forgotten melody, and will make you remember your best day, your worst moment, that small thing you loved that was swallowed by all the other things of your life. And in the end, like the best songs do, these stories will break your heart.

Steven Pinker, author of "The Better Angels of Our Nature" (Penguin)

[caption id="attachment_10303989" align="alignleft" width="186" caption=" "] [/caption]

[/caption]

Christmas is said to be a time of peace on earth and good will toward humankind, so what better choice than a trio of books that document how this seemingly treacly sentiment is closer to the truth than news-jaded readers would suspect? Within a single month, four books appeared that marshaled dates and data to show that the number and human costs of war are way, way down. My own depended heavily on primary research by the other three: Joshua Goldstein in "Winning the War on War," John Mueller in "War and Ideas," and Andrew Mack and his collaborators at the Human Security Report Project in "The Causes of Peace and the Shrinking Costs of War." Forty years after John and Yoko released "Happy Xmas," these books can amend the chorus: "War is (Almost) Over."

Mary Gabriel, author of "Love and Capital: Karl and Jenny Marx and the Birth of a Revolution" (Little, Brown)

"Tonight No Poetry Will Serve: Poems 2007-2010," by Adrienne Rich (W. W. Norton)

Among the thousands of words written and spoken in the past few years about our broken political, social and economic system, one thin volume of poetry published this past year stands out for me. Adrienne Rich’s "Tonight No Poetry Will Serve" is chillingly beautiful and blindingly clear in its depiction of where we exist as a people at the dawn of the 21st century. Rich’s poems, written between 2007 and 2010, employ very few words to describe the vast spectrum of violence – from state to personal – that gnaws at our lives until we are permanently disfigured – as a society and as men.

One poem in particular, “Ballade of the Poverties,” written in 2009, is truly unforgettable. It is an unflinching catalog of acts to which men and women are driven in order to survive.

There’s the poverty of the cockroach kingdom and the

rusted toilet bowl

The poverty of to steal food for the first time

The poverty of to mouth a penis for a paycheck

The poverty of sweet charity ladling

Soup for the poor who must always be there for that

There’s poverty of theory poverty of swollen belly shamed

Poverty of the diploma or ballot that goes nowhere

“Ballade” then proceeds to indict the “Princes of finance” and “Princes of weaponry” who do not see themselves as the cause of such misery.

Rich’s poems are filled with pain and suffering; her subjects prostrate, facing physical – or worse, spiritual death. They are victims of their own bad decisions and victims of the world in which they live. Yet, despite the near fatal despair of all who inhabit her pages, they are not defeated, and the reader, too, comes away oddly restored. Rich’s poems bestow a quiet dignity to even our most shameful humiliations and boldly condemn those who have created a society in which those humiliations must occur.

Helen Oyeyemi, author of "Mr. Fox" (Riverhead)

[caption id="attachment_10303995" align="alignleft" width="186" caption=" "] [/caption]

[/caption]

"The Little Shadows," by Marina Endicott (Doubleday Canada)

Marina Endicott's "The Little Shadows" is my book of the year. It's mainly about four women: Aurora, Clover, Bella and their mother -- a family trying to make a living on the early-20th-century Canadian vaudeville circuit. Here are all the highs and lows and uncertainties that are part of the business of entertaining people. Not that this is a narrative about becoming famous, it's about getting enough to eat and finding ways to improve your work. The sisters are alert to the kind of pragmatism that enables you to finish a delicious oyster dinner despite just having had bad news. Think of your favorite stories about sisters -- the gravity, levity and subtlety with which the lives of siblings are woven together; Endicott puts her own spin on that. She also thinks and writes wonderfully about art and artifice. Vaudeville puts sentiment up for sale, but the thing is not to surrender it cheaply, and this story asks that the performance of feeling be approached with care. After all, as a character in the novel points out, art does such uncanny and essential things with the experience of being alive: "Perfecting it. Making it -- realer, or less real. We are only pointing at the moon, but it is the moon."

Ali Smith, author of "There but for The" (Knopf)

"Down the Rabbit-Hole," by Juan Pablo Villalobos (And Other Stories Publishing)

The percentage of books in translation in the U.K. publishing market is so pitifully small (it averages out yearly at about 3 percent), and small independent publishers are under such economic pressure just now, that it's pretty much a miracle that the book I most loved this year got published here at all. "Down the Rabbit-Hole," by the Mexican writer Juan Pablo Villalobos, translated by Rosalind Harvey and published by And Other Stories, is a deft piece of ventriloquism and irony, a story of a child growing up in a drug cartel that subtly shakes up everything from the immediacy of language to the heritage of literary wonderlands.

Teju Cole, author of "Open City" (Random House)[caption id="attachment_10303996" align="alignleft" width="186" caption=" "] [/caption]

[/caption]

"Memorial," by Alice Oswald (Faber and Faber)

The best book I read this year was Alice Oswald’s “Memorial," a translation of all the death scenes in the Iliad, set in sequence. It is an enormously successful long poem, sure-footed, full of unforgettable detail: “flower-lit cliffs,” “letting the darkness leak down over his eyes,” “a stone stands by a grave and says nothing.” Oswald has a marvelous ear for effective anachronism: two brothers are “proud as astronauts/ And didn’t want to farm any more/ And went riding out to be killed by Agamemnon.”

Each man who dies is named, in all caps: LYSANDER, ECHEPOLUS, PATROCLUS, HECTOR. Each death is described in detail. The effect is like that of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial: names carved into black rock, lived lives gleaming behind each name. With a scrupulous eye, the sham nobility of war is indicted over and over again.

Oswald’s poem shows how, in the midst of military madness, a specific “instant unspeakable sorrow” can resound undimmed all the way from Homer’s time to ours.

Lev Grossman, author of "The Magician King" (Viking Adult)[caption id="attachment_10303997" align="alignleft" width="186" caption=" "] [/caption]

[/caption]

"A Dance With Dragons," by George R.R. Martin (Viking Adult)

The best book I read this year was George R.R. Martin’s "A Dance With Dragons."

I don’t say that lightly. I read a lot of fiction, of all genres, literary fiction very much included, but in every way that matters — its craftsmanship, its ambition, the emotions it stirred up in me — Martin’s novel was the most satisfying reading experience I had this year.

It's easy to dismiss Martin's books as commercial, or populist, or whatever derogatory label you want, but that's a mistake. The work he's doing, reinterpreting the epic fantasy tradition of Tolkien, is vital cultural work, and he's doing it with ridiculous brilliance and ruthlessness. He's turning epic fantasy from a myth into a novel: a story that tells us things about how we live now, our moral confusions and particular sorrows, and that consoles us for them.

As for craft: Yeah, on the level of sentence, you couldn't stack "A Dance With Dragons" up against Jeffrey Eugenides’ "The Marriage Plot," or Alan Hollinghurst’s "The Stranger’s Child." But as a plotter, an orchestrator and pacer of narratives that weave around and resonate with each other, Martin leaves them far, far behind. Is that important? Maybe not to the people who give out Pulitzers. But it's important to me. It's why "A Dance With Dragons" is the best book I read this year.

Tom Perrotta, author of "The Leftovers" (St. Martin's)

"The Sisters Brothers," by Patrick deWitt (Ecco)

A novel that's really stuck in my mind this year is "The Sisters Brothers" by Patrick deWitt. It's an odd gem, a darkly funny picaresque set during the Gold Rush that has one of most engaging and thoughtful narrators I've come across in a long time. The fact that this narrator happens to be a hired killer -- slightly less terrifying than his psychopathic brother -- somehow only adds to the pathos and humor of his dilemma. The novel belongs to the great tradition of subversive westerns -- "Little Big Man," "True Grit," "No Country for Old Men" -- but deWitt has a deadpan comic voice and a sneaky philosophical bent that's all his own.

Paula McLain, author of "The Paris Wife" (Ballantine)

"State of Wonder," by Ann Patchett (HarperCollins)

My hands-down favorite read of 2011 was Ann Patchett’s "State of Wonder." Patchett isn’t a stylist or plotting magician so much as a world builder. In "Bel Canto," that world’s a terrorist-ridden vice-presidential mansion in South America where — quite impossibly — great beauty, tenderness and stunning acts of kindness work to alter her characters’ destinies. In "State of Wonder," we’re in the Brazilian Amazon with Marina Singh, a research doctor for a pharmaceutical company sent on a sudden mission to recover the remains of a friend and colleague who’s died under murky circumstances. Exotic, and unfathomable and terrifying remote, the jungle demands that Marina adapt — or be eaten alive. How she changes and doesn’t in this setting, and in relation to the other brilliantly drawn characters, held my attention with a raptness rare for me. I have small children, and can rarely read more than a chapter a night before I pass out — and yet Patchett’s novel had me up until 1 a.m. two nights running, and reminded me of why I love to read — to be utterly swept away, in the sure hands of a consummate storyteller, a Scheherazade.

Justin Torres, author of "We the Animals" (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt)[caption id="attachment_10303998" align="alignleft" width="186" caption=" "] [/caption]

[/caption]

"If You Knew Then What I Know Now," by Ryan Van Meter (Sarabande Books)

The book I keep beating the drum for is Ryan Van Meter's memoir-in-essays, "If You Knew Then What I Know Now." Tender, yet unflinching, Van Meter's essays defy easy classification. The essay on the etymology of the word "faggot" is an especially genius and delightful riff, but every essay here is careful, considered and somehow urgent. I've been pushing it on folks all year and getting nothing but thank you, thank you, thank you, in return.

Lauren Redniss, author of "Radioactive: Marie & Pierre Curie -- A Tale of Love and Fallout" (It Books)

"Prints and the Pursuit of Knowledge in Early Modern Europe," ed. Susan Dackerman (Harvard Art Museums)

In September 2011, an exhibition called "Prints and the Pursuit of Knowledge in Early Modern Europe" opened at the Arther M. Sackler Museum at Harvard. The catalog, which shares the exhibition's title, reproduces 16th-century woodcuts and etchings displayed in the show. The prints and accompanying essays look at the interplay of science and art in the 16th century. There are anatomical illustrations that fold out to reveal the organs of the human body, six artists’ depictions of the rhinoceros (an animal they had never seen), maps, globes, sundials and a vision of Hercules so muscled he appears to be made of grapes. The works are most interesting in their inaccuracies, delineating the edges of knowledge of the time. In the terrific strangeness of the images, we experience the wonder that must have pulled these artist-scientists to their subjects.

Touré, author of "Who's Afraid of Post-Blackness? What It Means to Be Black Now" (Free Press)

[caption id="attachment_10304002" align="alignleft" width="186" caption=" "] [/caption]

[/caption]

"Moonwalking With Einstein," by Joshua Foer (Penguin Press)

I had already purchased "Moonwalking With Einstein" and was walking down the street flipping through it when I realized it was not written by the author of "Everything Is Illuminated." That book is by Jonathan Safran Foer. "Moonwalking" is by Joshua Foer, Jonathan’s little brother. What a failure of memory! I saw the name Foer and recalled the intense reading pleasure I’ve gotten from Jonathan and didn’t remember that Jonathan Foer’s first name ends with an “N” and not a “SH.” Idiot. I think there might’ve been a tiny voice in my head that said “Doesn’t Foer go by three names? Wonder when he dropped the Safran.” I did not listen to that voice.

Anyway, my mistake was fortuitous — it turned out to be a great book — and serendipitous because it helped me with my memory. The little brother’s book is as good as anything the older one’s done, which is saying a lot. "Moonwalking" is a non-fiction book with a novelistic plot, albeit one that tells you its end right away — that Foer, a relatively average dude with a normal memory, will win the U.S. Memory Championships after training for just a year. This adds to the drama because it makes you infinitely more curious about the journey and the details of his training than if he was just entering on a George Plimpton-esque lark. Knowing that his methods will work makes the journey an irresistible ride.

The book is personal and memoiristic, but ultimately, Foer is an Everyman, and you feel buoyed with the confidence that if only you took the time to practice as he did then you, too, could one day compete in the memory championships. In describing his practice methods in detail, Foer takes you into the life of the mind and helps you understand how to best use your memory. The modern approach to memorization (committing letters and numbers to memory) has limited potential, he learns, because that doesn’t fit with how our brains are wired, systems that were constructed back in the caveman days. Our memories are made to recall images. It’s easier to recall items you want to remember — say, things on a grocery list or the order of a deck of cards — if you place them along an imagined route in a “memory palace,” a structure one can mentally walk through. Images that are unusual are more likely to be sticky and images that involve sex are very sticky. One of my favorite mnemonic techniques in the book involves imprinting people’s names by picturing them making out with another person who has the same name. My ability to recall women’s names has improved dramatically. (I don’t do this with men.)

Foer elegantly weaves between learning the science of memory from the smart and kooky characters in this intense subculture and the personal story of developing into a memory stud, which adds up to a sort of elaborate party trick because he still might forget to grab his keys before he leaves home. Still, I learned how to use my mind better and read breathlessly as he crept through the big contest, inching toward winning an event he’d already told me he was going to win.

James Gleick, author of "The Information: A History, a Theory, a Flood" (Pantheon)

"Embassytown," by China Miéville (Del Rey)

I'm still trying to catch up with my reading for 2010. But of this year's crop, so far I haven't read anything I liked better or admired more than China Miéville's "Embassytown." It is exciting, virtuosic, and profound. In a narrative of adventure and epic conflict, Miéville, it turns out, has something new to say about language, about metaphor, and about the nature of truth, spoken and unspeakable.

I suppose this book will be found shelved in the sci-fi section. It has monsters and planets not our own. But if it isn't literature, I don't know what is.

Shann Ray, author of "American Masculine" (Graywolf Press)

"Volt," by Alan Heathcock (Graywolf Press) and "Beautiful Unbroken," by Mary Jane Nealon (Graywolf Press)

I want to let people know, "Volt" is what it is! Lightning to the bones. A gorgeous and stark and deeply redemptive collection. I read what was inside the pages, and I was shaken. "Volt" is a grouping of stories as rewarding as it is written in muscular and emotionally discerning prose. The stories are distinct, evocative works of art, filled with torque and interior resonance, and together they become an electric storm of massive proportions. You will not come out unscathed. The moral undertow created by Alan Heathcock’s splendid book of dark gems takes people through death into an increased sense of the reality of life. The journey is like being shattered and put back together again more beautiful than before. When I finished “The Staying Freight” and the subtle, ardent turn of humanity in “Lazarus,” as well as the collection as a whole, I felt gratitude for the literature of America. I felt as if I’d traveled many miles in the wilderness of the human heart, and at the end of my journey I found a sense of rest and recompense, a true and often visceral justice, and profoundly, in all that terrible darkness, there was light. It has been some months now since I first read Volt, but still I find myself ruminating over the sheer beauty and power of these stories, the human touch, the divine mystery.

In her deeply felt and graceful memoir, Mary Jane Nealon takes vital risks, and in the heart of readers, the reward is great. In the core of our most significant losses, she reveals the stark beauty of people as physical, tangible, oriented toward tragedy, and interwoven with a love that is often inexpressible, and always irrevocable. Written with generosity and the enduring resonance of the best poetry, Nealon’s prose is worthy and enduring and a true gift. As a nurse who travels pathways of chronic illness and human suffering with acuity, clarity and tenderness, she leads us deeper and deeper into the soul of the nation, a place where we encounter the self, family and each other in all our desperation and all our hope. By leading us into the depths of life, death, people and love, in "Beautiful Unbroken" Mary Jane Nealon makes us feel as if we’ve been carried through an unforeseen abyss by a powerful and fierce angel. When we emerge and find ourselves set back on level ground, we greet one another with reverence and peace.

Jessica Hagedorn, author of "Toxicology" (Viking Adult)

"Open City," by Teju Cole (Random House)

If I have to pick just one book published in 2011, it would have to be Teju Cole’s first novel, "Open City." It’s lean and mean and bristles with intelligence. The multi-culti characters and streets of New York are sharply observed and feel just right. Cole’s narrator, Julius, takes long walks and remembers the complicated, vibrant Nigeria of his youth. Toward the end, there’s a poignant, unexpected scene in a tailor’s shop that’s an absolute knockout.

Ross Perlin, author of "Intern Nation" (Verso)

"Debt: The First 5,000 Years," by David Graeber (Melville House)

Even if you're not up to your neck in credit card debt, reeling from a subprime mortgage or buried under student loans, you owe it to yourself to read David Graeber's radical, accessible, ultimately mind-blowing "Debt: The First 5,000 Years." A professional anthropologist actively involved in the the Occupy Wall Street movement, Graeber demonstrates how arguments about debt and credit have dominated political and religious life since the beginning of settled civilization. Words like "redemption," "guilt" and "sin," originally borrowed from the language of debt and credit, were transformed into moral imperatives. Countless revolutions started with the destruction of debt records. "For most of human history -- at least the history of states and empires," writes Graeber, "most human beings have been told they were debtors."

Graeber moves easily from his own fieldwork in Madagascar to eighth-century Japan, from the Rig Veda to the IMF, fortifying his arguments with evidence from the full spectrum of human diversity and providing a masterful survey of the historical and anthropological literature on debt. He makes short work of several unexamined dogmas held dear by economists -- that barter preceded money, that markets have ever existed independently of states, that economic and social policy can be neatly separated. For Graeber, the essence of debt is "agreement between equals to no longer be equal." Power, violence, and ruthless accounting have only made debt even more pernicious -- after reading Graeber, you'll never look at deficit spending, the U.S. national debt, third-world debt or the current economic crisis in the same way again. By the end, you may find yourself seriously considering Graeber's proposal for a biblical-style "jubilee" of debt forgiveness and, in your own life, heeding the advice of Polonius in "Hamlet": "Neither a borrower nor a lender be."

Frank Bill, author of "Crimes in Southern Indiana" (FSG)

"Volt," by Alan Heathcock (Graywolf Press)

After consuming "Volt" by Alan Heathcock, the reader will need to down several fingers of Knob Creek and pop a few Vicodin to numb themselves. Like a teething child, the pain of the characters is felt throughout a landscape smeared by darkness and beauty in a way I’ve not read since Cormac McCarthy, Daniel Woodrell or Larry Brown. Heathcock's prose rifles through the sometimes violent lives of men, women and children while offering adventure, loss, mystery and redemption. The wounds one has absorbed when reaching that final word on the last page is 100 percent visceral satisfaction accompanied by two black eyes and a bloody nose, which is something I want to feel while reading a book.

Paul Hendrickson, author of "Hemingway's Boat: Everything He Loved in Life, and Lost, 1934-1961" (Knopf)

"Higher Gossip: Essays and Criticism," by John Updike (Knopf)

"Higher Gossip," John Updike's latest collection of essays and reviews and criticism. Killer photograph on front and all that shining language inside, which only makes me long for even more from the master who went away from us all too soon and suddenly.

David Whitehouse, author of "Bed" (Scribner)

"Busy Monsters," by William Giraldi (W.W. Norton)

Mr. Giraldi’s story is an oily pig, slippery and fast and frustrating. But if you like your prose with meat and hair, what a catch when you pin it down in the mud.

Its hyper-articulate, camp, polarizing protagonist Charles Homar – a magazine columnist - sets about his own odyssey, to track down and win back she who has his heart. She, meanwhile, has run off in pursuit of a giant squid. His journey is a ripping yarn, through plentiful freaks and treachery, told with dizzying bombast. Mostly it’s a fine comic prodding of the sometimes farcical art of storytelling – tales of the Sasquatch, UFOs, the elusive squid -- which Mr. Giraldi seems to know an often brilliant amount about. It is funny, rich and so inventive that it almost speaks in tongues. I was a tiny bit dazzled.

Joshua Foer, author of "Moonwalking With Einstein: The Art and Science of Remembering Everything" (Penguin Press)

"1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created," by Charles Mann (Knopf)

My favorite book of the year was Charles Mann's gripping tale of the Columbian Exchange, "1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created." It is, in a way, mind-blowing enough to try to imagine the Italians without tomatoes or the Irish without potatoes, but these are just footnotes in the scheme of the colossal, earth-shattering event that took place when the two hemispheres were reunited in 1492. Nothing in human history so dramatically, or so quickly, changed the face of the planet. Charles Mann's recounting is Big History at its best, a book as epic as its subject.

Amanda Foreman, author of "A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War" (Random House)

"Jerusalem: The Biography," by Simon Sebag Montefiore (Knopf) and "The Storm of War," by Andrew Roberts (HarperCollins)

[Simon Sebag Montefiore's] comprehensive and entertaining history of Jerusalem was hailed by the New York Times, which praised Montefiore, the author of two books on Stalin and another on Prince Potemkin, for his "fine eye for the telling detail, and also a powerful feel for a good story — so much so that his vastly enjoyable chronicle at times has a quasi-mythic aspect. He cheerfully borrows snippets of Scripture, legends and dubious eyewitness accounts, weaving them into his larger narrative." Though long, "Jerusalem" trips along at a cracking pace, making it unputdownable. It is traditional narrative history at its best.

"The Storm of War" is Roberts' magnum opus, bringing together much that he had to leave out of his brilliant "Masters and Commanders." The New York Times called it "a splendid history" and praised his effort to answer the question, "how did the Wehrmacht, the best fighting force, lose World War II?" The reader is "treated to a brilliantly clear and accessible account of the war in all of its theaters: Asian, African and European. Roberts’s descriptions of soldiers and officers are masterly and humane, and his battlefield set pieces are as gripping as any I have ever read. He has visited many of the battlefields, and has an unusually good eye for detail as well as a painterly skill at physical description." Roberts' grasp of military history is unerring and robust, making his descriptions of various battles positively thrilling. For a well-worn subject, "The Storm of War" feels remarkably fresh and exciting.

Dean Bakopoulos, author of "My American Unhappiness" (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt)

"Busy Monsters," by William Giraldi (W.W. Norton)

I don’t have all that much time to read for pleasure anymore: Two kids, multiple deadlines, teaching in two different writing programs and traveling to do readings tend to take away those vast stretches of emptiness I once had when I was young and working as a bookseller, awash in free books and spare time. Back then, a book could linger, sewing quiet beauty, unfolding like a meandering and marvelous secret.

Now, when I read a novel, I want it to shake me up. I want a novel that takes risks, bellows too loudly, seduces and disgusts. I want to feel like I’ve been on a road trip with a deliriously entertaining companion, one I sometimes love and occasionally hate, and I want to feel like I’ve just heard a ton of great new music, played by bands that I never knew existed. But I also want to feel wrung out, like I’ve been through more greasy food, cheap beer and Motel 6 beds than I can stand. I want a novel to leave me exhausted, road-weary, spent. In short, I don’t want to waste my time. I want to feel something.

For my money, the most raucous and enveloping novel of 2011 was William Giraldi’s debut novel, "Busy Monsters," which tells the story of Charles Homar. Homar’s quest to win back his lover by any means necessary is a screamingly funny, manic and innovative contemporary "Odyssey." It’s the novel of a lovesick sad sack aiming to prove his manhood and maintain his dignity, in a world that seems void of both authentic experiences and reasonable comforts. It’s a novel about a smart man who understands that a surfeit of brains doesn’t make one feel happy or useful or strong. Is it wildly flippant and erratic and sometimes uneven? You bet it is. Did it make me laugh, raise my heart rate and find me howling with sympathy? Yes, it did. Over and over again, amen.

Howard Blum, author of "The Floor of Heaven: A True Tale of the Last Frontier and the Yukon Gold Rush" (Crown)[caption id="attachment_10304003" align="alignleft" width="186" caption=" "] [/caption]

[/caption]

"Before I Go to Sleep," by S. J. Watson (HarperCollins)

I sure got caught up in "Before I Go to Sleep" by S. J. Watson. On one level, the first-person narrative spins out as a taut and suspenseful thriller. On another (and more resonating) level, Watson had me mulling the nature of memory, what we choose to remember and what we choose to forget, and how we are defined by our memories. Not least, the tale raises questions about how we perceive those we love, and the sources and objectivity of those perceptions. Sure, it's a page-turner, but it's the roiling background full of smart musings about the choices we make consciously and unconsciously in matters of the heart that gives the story a special appeal.

Something else: the narrative structure of "Before I Go To Sleep," part diary, part first-person tale, a story spun by a character who can't even trust herself, is a daunting high-wire act that Watson pulls off flawlessly. As one writer to another, I sure admired (envied, more precisely) his skill.

Yes, Julian Barnes covered a bit of the same narrative territory this year in his elegantly written "The Sense of an Ending." However, I must say S. J. Watson's cerebral thriller grabbed me more. It had a place on my nightstand for a week this summer, and when it was finished, I deeply missed being able to delve into a new chapter.

Kevin Wilson, author of "The Family Fang" (Ecco)

"Silver Sparrow," by Tayari Jones (Algonquin)

In "Silver Sparrow" -- an amazing novel about a man with two families, one hidden and one public -- Jones does something breathtaking and difficult: She renders a unique family dynamic with such precision and sensitivity that it becomes universal. It is amazing to watch, time and time again in this book, how Jones reveals the ways in which family both creates and destroys our identity. Jones' previous novels are fantastic, but this book feels like a masterpiece.

Mark Derr, author of "How the Dog Became the Dog" (Overlook)

"Train Dreams," by Denis Johnson (FSG)

Widely and justly celebrated for "Tree of Smoke" (2007), his sprawling National Book Award-winning Vietnam War novel, a prolific poet and playwright, Denis Johnson is to my mind the master of the short long fiction -- whether a novella, extended short story or truncated novel. "Train Dreams," a novella first published in "slightly different form" in the 2002 Paris Review, shows the master at the height of his power. Hard-edged, economical, compact prose seamlessly blends the real and surreal. Sparse, pointed dialogue gives individual voice to each character, no matter how minor. Characters are participant in but not necessarily party to their own lives.

"Train Dreams" is a haunted and haunting work that begins with the failed lynching of a Chinese railroad worker speaking a language none of his attackers understand and ends with a faux wolfboy’s howl of lamentation that comes to subsume all sound. Between them lies the story of Robert Grainier, an orphan born around 1886 who dies a hermit more than 80 years later in Idaho, leaving no heirs. “Almost everyone in those parts knew Robert Grainier, but when he passed away in his sleep sometime in November of 1968, he lay dead in his cabin through the rest of the fall, and through the winter, and was never missed.” Relying on wolves, coyotes, dogs, a wolfchild, a ghost and an array of eccentric characters -- the young Elvis Presley makes a cameo appearance -- as well as on railroads and conflagrations, Johnson makes memorable the life of an unmemorable man. And that’s just the surface.

Alan Heathcock, author of "Volt" (Graywolf Press)[caption id="attachment_10304004" align="alignleft" width="186" caption=" "] [/caption]

[/caption]

"Train Dreams," by Denis Johnson (FSG)

It’s been an amazing year in books. I loved Alexi Zentner’s heartbreaking and mysterious novel, "Touch." Annick Smith’s "The Call" was an amazing feat of intellect and storytelling. Siobhan Fallon's "You Know When the Men Are Gone" was not just great drama, but also felt like an important book for our times. Bonnie Jo Campbell’s "Once Upon a River" was a masterful odyssey, and "The Cat’s Table" by Michael Ondaatje made me think that a great master may have written his finest book in a long career of fine books.

However, no other book engaged the full capacities of my intellect, emotion and imagination like "Train Dreams" by Denis Johnson. Johnson’s stories and novels always vibrate with a strange and undeniable intensity. I believed his collection "Jesus’ Son," and his novel "Tree of Smoke," were masterpieces. Yet "Train Dreams" is my favorite of all of his work, as this slim novel follows Robert Grainer from working on building great railroad bridges in northern Idaho, and into a weird and arresting epic of loss that spans decades and reads like the story of America in miniature, with not a word wasted, not a moment spared to allow a reader to look away or catch their breath. This book had a profound effect on me -- after I’d read the final words in "Train Dreams," I felt as if I’d been gifted something ancient and true, and immediately opened the book back to Page 1 and began to read it again.

Andrew Krivak, author of "The Sojourn" (Bellevue Literary Press)

"Train Dreams," by Denis Johnson (FSG)

The book that captured my attention the most in 2011 was Denis Johnson’s "Train Dreams." In spite of – or, perhaps, more properly, because of – its spare rendering of one man’s life, labor and imagination at the turn of the last century, I found myself reading this novella over and over again, each time discovering a new and subtle layer of narrative or quietly emerging motif, until not one word seemed extraneous or disconnected from the whole, vast, beautiful, dreamlike portrait of Robert Grainier, his lost family, and his lost America.

Elissa Schappell, author of "Blueprints for Building Better Girls" (Simon & Schuster)

"Stone Arabia," by Dana Spiotta (Scribner)

I was hooked on "Stone Arabia," Dana Spiotta’s stunning portrait of the love and rock music that bonds a pair of siblings from their youth in the '70s to the present and middle age, from Page 1. In virtuoso prose Spiotta captures our modern obsession with celebrity, the hell of making art and the age-old sorrowful understanding of what it’s like to grow up and discover you aren’t who you used to be, and won’t become what you always envisioned.

Peter Orner, author of "Love and Shame and Love" (Little, Brown)

"Volt," by Alan Heathcock (Graywolf Press)

I always wonder why short story collections rarely feature on end of the year lists like this one. Among the riveting new books I have read this year, by far, is Alan Heathcock's collection, "Volt." The characters are beautiful and unforgettable, like members of my own family, like members of yours. And the writing is raw and never fancy. Here's a passage from "Peacekeeper," which has some of the best stuff about floods since Faulkner's "The Wild Palms": "Spring 2008: In the flume between hillocks the floodwaters converged, dammed by logs and mud, a kitchen chair, a section of roof, a child's plastic slide, refuse thick and high and brown water sluicing through random gaps." Other terrific collections published this year include Edna O'Brien's "Saints and Sinners," Elissa Schappell's "Blueprints for Building Better Girls," Steve Almond's "God Bless America" and "Death Is Not an Option" by Suzanne Rivecca.

Hector Tobar, author of "The Barbarian Nurseries" (FSG)

"The Swerve: How the World Became Modern," by Stephen Greenblatt (W.W. Norton)

Some years back, Stephen Greenblatt gave us what is arguably the best biography of Shakespeare ever written. "Will in the World" combined the historian’s craft with the keenest insight into the biggest clue Shakespeare left us about the man he was — his literary oeuvre. What emerged was an intimate portrait of a man of humble origins dealing with the birth of a new England and the death of an old one. In "The Swerve," Greenblatt pulls off an even grander feat of historical recovery: showing us how one man’s dogged, improbable search for beauty and language helped plant the seeds of the Enlightenment.

"The Swerve" is the story of how a Renaissance book hunter roamed through old German monasteries until he discovered an ancient Roman poem that had been forgotten for more than a millennium. Greenblatt tells this tale with a novelist’s eye for character and place. We travel to ancient Roman villas, meet a corrupt pope, and see the work of the monk-scribes who kept classic Roman and Greek texts alive throughout the Middle Ages. More important, Greenblatt shows us all the ideas that were unleashed by the discovery of that single, epic poem. "The Swerve" will always stay with me because it’s revealed to me how many of the values that inform our modern lives were born in individual passion and sacrifice. When we say we believe in the “pursuit of happiness,” we owe a debt to an ambitious, 15th-century Vatican functionary with excellent penmanship: Who knew?

Debbie Nathan, author of "Sybil Exposed: The Extraordinary Story Behind the Famous Multiple Personality Case" (Free Press)

"Lost Memory of Skin," by Russell Banks (Ecco) and "Sex Panic and the Punitive State," by Roger Lancaster (University of California Press)

The Kid – that’s all author Russell Banks ever calls the hero of his new novel, "Lost Memory of Skin." The Kid is a taciturn, white, 22-year-old Floridian — and a convicted sex offender. He makes his home under the embankment of a bridge. It’s one of the only places around that’s farther than 2,500 feet from places frequented by children, and thus, one of the few places where paroled sex criminals are allowed to reside. (Another is an Everglades-like swamp, filled with orchids and alligators.) The embankment’s denizens hide in jerry-rigged tents amid trash and urine buckets. No longer are they citizens, Banks writes. Society has come to see them as merely “a bridge between what passes for normal human beings and animals ... like chimpanzees or Neanderthals."

Yet The Kid is skinny, goofy, sort of sweet. Almost a boy. And a virgin, as readers learn partway through the book.

So why is he a sex offender? He seems to have gotten caught in a sting resembling TV’s “To Catch a Predator,” in which a teenaged girl’s dad seems to have pretended to be his own daughter, seemingly taking pleasure in talking over the Internet like a horny young female, then calling the cops on a seeming seducer. Or maybe, in reality, there was no sting. Maybe a real girl really chatted online with The Kid, and he really tried to take advantage of her. Banks makes the truth hard to tell.

All truths are murky in "Lost Memory of Skin." Attempting to escape the tents and piss buckets, The Kid emigrates to a houseboat on the federal swamp, the way Huck Finn claimed his raft on the Mississippi. He thinks about America and about himself, finally deciding that getting arrested for sex offending is the only thing that ever made him feel real, and realizing that to become a man, he must return to hell -- to the embankment. In his tragic and deluded understanding, The Kid resembles Gyorgy, the Hungarian Jewish teenager in Imre Kertesz’s "Fatelessness" – shipped by the Germans to Auschwitz and Buchenwald, yet rationalizing the Holocaust as correct, emanating as it does from an efficient and all-powerful authority.

Anthropologist Roger Lancaster’s "Sex Panic and the Punitive State" casts a nonfictional and thought-provoking perspective on Banks' metaphors. For Lancaster, America’s obsessional fear these days of child molesters, and our eagerness to dehumanize all suspects, helps the government to monitor and punish practically everyone (including people who have nothing to do with sex offending), the better to extend the state’s control over everyone. Blacks and the poor used to be the main victims, but latter-day activism has made it un-p.c. to openly focus on them. But white men! If they can be punished, Lancaster writes, then everyone can be. This idea from the social sciences intersects with literature when it comes to Banks’ tale of The Kid. Read together as different takes on the same idea, "Sex Panic" and "Lost Memory of Skin" were fascinating bookends for me.

David King, author of "Death in the City of Light: The Serial Killer of Nazi-Occupied Paris" (Crown)

"The End: The Defiance and Destruction of Hitler's Germany, 1944-1945," by Ian Kershaw (Penguin Press)

I particularly enjoyed Ian Kershaw's "The End: The Defiance and Destruction of Hitler's Germany, 1944-1945," a magnificent scholarly portrait of the final months of the Third Reich.

Among other things, Kershaw examines the difficult question of why German society remained so cohesive in the wake of catastrophe. His book -- the culmination of almost 40 years researching Adolf Hitler and Nazi Germany -- is an important, provocative study of the structures and mentalities of the Nazi will to fight on until the bitter, horrific end.

Lydia Millet, author of "Ghost Lights" (W.W. Norton)

"Bohemian Girl," by Terese Svoboda (University of Nebraska Press)

Terese Svoboda writes some of the loveliest prose in America but has been startlingly overlooked by literary critics and readers. This year the University of Nebraska Press published my favorite book of hers so far, even better than "Tin God" -- the beautiful novella "Bohemian Girl." It’s set in 1861 but might as well not be; as with other Svoboda books, its language is both modern and passably archaic -- translucent, elevated but not pretentious, and often sly. A slave girl sets off cross-country to escape a madman who wants to use her bones in a mound … please, read the rest for yourself.

Julie Salamon, author of "Wendy and the Lost Boys: The Uncommon Life of Wendy Wasserstein" (Penguin Press)

"Almost a Family," by John Darnton (Knopf)

Full disclosure: I worked for John Darnton for a brief spell, when he was culture editor at the New York Times. It was common knowledge that his father had been a war correspondent for the Times, killed on duty during World War II, when his second son was just a baby. John Darnton — that baby — grew up to become a foreign correspondent, just like his father. Great story -- resonant with newspaper and personal mythology, but not nearly as profound or absorbing as the messy, heartbreaking truths Darnton discovered while researching this compelling memoir. Tootie and Barney Darnton, his parents, were driven by grand ambitions matched by their frailties. Darnton, author of several best-selling novels, deconstructs wartime and personal drama with the powerful combination of a seasoned journalist’s instincts and an aching son’s need to know. He’s written a brave and beautiful book.

Jo Ann Beard, author of "In Zanesville" (Little, Brown)

"Townie," by Andre Dubus III (W.W. Norton)

A stark and elegant account of how Andre Dubus III got from there to here. There being the hardscrabble mill town neighborhoods he was raised in, along with his three siblings who were abandoned, for all practical purposes, by their eminent father, the short story writer Andre Dubus II, who lived a town or two over. Andre and his siblings were left to roam the streets, protecting each other when they could and scattering when they couldn’t, all while their mother strove to raise their very low standard of living. The book begins with a wincing and beautiful scene of the teenage narrator, who has somehow been invited to go jogging with his father and is trying to find a pair of proper shoes in the chaotic house. “Suzanne, can I borrow your sneakers?” he asks his sleeping sister, whose room smells like dope and cigarettes. “I’m running with Dad.” And that italicized word sets the stage for everything that follows.

John Jeremiah Sullivan, author of "Pulphead: Essays" (FSG)

"I Have Always Loved the Holy Tongue," by Anthony Grafton and Joanna Weinberg (Belknap Press of Harvard University Press)

A book that floored me in 2011 was "I Have Always Loved the Holy Tongue," by Anthony Grafton and Joanna Weinberg. The subtitle gets at the subject field -- "Isaac Casaubon, the Jews, and a Forgotten Chapter in Renaissance Scholarship" -- but does less to suggest the book's drama and style. Princeton professor Grafton is as gifted a writer as he is a historian -- something you know if you've read his illuminating book about footnotes -- and Weinberg is a preeminent Hebraist at Oxford. Each contributed his or her expertise, and together they've done nothing less than reconstruct a lost chamber in one of the major Renaissance minds.

Isaac Casaubon is only quasi-remembered today for having bequeathed his name to the dry old scholar character in George Eliot's "Middlemarch," but Casaubon the man was deeply passionate in both learning and life (he vigorously wooed a printer's daughter and is said to have fathered 18 children by her). Born of French-Swiss Huguenot refugee stock (like Rousseau), he eventually settled in England, and did as much as anyone in the 16th and early 17th centuries to establish the model of intellectual rigor that we continue to associate with "serious scholarship." He was a classicist primarily, and as such both a linguist and a historian, who made earth-clearing strides in those disciplines, and specifically in bringing them together. What's less known, and indeed was virtually unknown before now, is the depth of Casaubon's interest in Hebrew texts and historical Jewish culture.

To excavate this by-no-means-insignificant aspect of his thought, Grafton and Weinberg summon a dauntlessness of research that would earn a nod of respect from the master himself. Many of their extensive primary sources are tiny, deciphered marginal notes from Casaubon's books and copybooks (which they tracked down in libraries all over Europe), as well as obscure Latin correspondence with his academic friends and foes. They find a thinker fascinated with Jewish language and history at a time of near-ubiquitous anti-Semitism, when Jews themselves were forbidden from living in England, and when any Christian writing on ancient Judaism had to follow a distorted, villainizing narrative, no matter what the facts said. In this book, we find Casaubon struggling to subvert those obstacles, but also hobbled by them, in that his own ideas about Jews could lead him into error.

Caitlin Horrocks, author of "This Is Not Your City" (Sarabande Books)

"Swamplandia!" By Karen Russell (Random House)

I’d been looking forward to Karen Russell’s first novel since I read her short story “St. Lucy’s Home for Girls Raised by Wolves” in "The Best American Short Stories 2007" (the other literary crush I discovered in that anthology: Lauren Groff). I’ve loved Russell’s other short stories, too, but her bio always reminded the reader that there was a novel about a family of alligator wrestlers just over the horizon. Now "Swamplandia!" has arrived, and it’s miraculous. Her sentences make my jaw drop, and then make me want to write better sentences. Whether she’s describing Florida exteriors (“The road spun behind us like something the car was excreting, yards and yards of black filament”) or human interiors (“She would push our hair back from our cool liar’s scalps and bring us noodles and icy mainland colas as if happy for an excuse to love us like this”), her writing is surprising and wise and, when it isn’t heartbreaking, just plain fun. Russell makes whole worlds in this book, and makes them real, and I loved spending time in a mossy gator park, surrounded by ghosts.

Deborah Baker, author of "The Convert: A Tale of Exile and Extremism" (Graywolf Press)

"The Submission," by Amy Waldman (FSG)

On one level, "The Submission" seems as much a New York tale of the past decade as "Bonfire of the Vanities" was for the 1980s. Amy Waldman took the headlines, added New Yorkers, an exploding controversy and concocted a plot that often seems to proceed in a parallel universe to the one we have dumbly been trying to find our way around in for the last 10 years.

At the novel’s heart is a true Manhattan wallah, an architect with a skyscraping ego. Like Wolfe’s Master of the Universe, he is a man in a hurry: Even his name is abbreviated. This impatience leaves him no time for office politics, artful ruminations on his suburban childhood, his immigrant parents or his string of girlfriends. Instead, denied a promotion he felt was rightfully his, he submits a design for the 9/11 memorial. Out of 5,000 anonymously submitted designs, his is chosen. But there is a problem. He is not the cosmopolitan and irreligious New Yorker he always imagined himself to be. He is not even the arrogant prick his girlfriend thinks he is. Mo’ Khan is a Muslim. "The Submission" turns on the ways in which the memorial’s jury, the politicians, lawyers, victims’ families, media and Khan himself, respond to this revelation.

There is really something to be said for a first-time novelist who presumes to tell the story of New York City’s effort to come to terms with the attacks of 9/11, not obliquely and allusively, but in a full-on page-turner. Waldman’s sense of irony is implacable and very much alive; I was unprepared for how nervy and dark this book proved. And while Khan is the novel’s load-bearing character, there are equally deft scenes of the city’s Muslims and 9/11 families struggling to make sense of or hay out of their sudden visibility. Waldman covered the attacks and their aftermath for the Times and then worked as a bureau chief on the subcontinent. This no doubt accounts for her incisive prose and a knowingness that goes well beyond an intimacy with the five boroughs. I came away from this book with a sharp sense of how the attacks changed us, all of us. Ten years on, we may finally be ready to look.

Anna Solomon, author of "The Little Bride" (Riverhead)

"Once Upon a River," by Bonnie Jo Campbell (W.W. Norton)

I’ll admit, I’m a sucker for smart, tough heroines. But Margo Crane, the scrappy, sharp-shooting, 16-year-old (depending on who asks) girl who guides us up and down her beloved Michigan river in Bonnie Jo Campbell’s “Once Upon a River,” took my breath away. Margo’s mother ran away, her father’s been killed: What she has left is her rifle, her rowboat, her instincts, and her very tender heart. As she skins rabbits, searches for her mother, and finds refuge with men of various repute (her sexuality refreshingly unapologetic), Margo becomes as real as any girl I’ve ever met, or been: She’s strange enough she might have been raised by the most decent sorts of wolves, yet she’s familiar, too, her needs startlingly simple: “She wasn’t a wolf girl or a murderer or an heiress [as Michael imagined]. She was a girl who needed some matches and gas for the outboard motor.”

I approached the end of this book with equal parts thrill and trepidation – not only for what might happen to Margo, but for myself; I was so immersed in her story, I didn’t want it to end. I realized that the book had transported me beyond the river. It made me see my own world anew – my car, my bottled milk, my assumptions about right and wrong, my buried instincts – as only the best fiction can.

Maxine Swann, author of "The Foreigners" (Riverhead)

[caption id="attachment_10304005" align="alignleft" width="186" caption=" "] [/caption]

[/caption]

"The Love of My Youth," by Mary Gordon (Pantheon)

Combining bracing intelligence with profound warmth, this update on Henry James, in which two Americans, once passionately in love, meet up again in Rome after 40 years apart, is without a doubt one of Gordon’s best.

In the same way that her protagonist, Miranda, comments on the statues she’s observing, Gordon, in her usual manner, walks right up to the object in question, stares it in the face and says what she thinks. And what she thinks – about passion, aging, ambition, pleasure, the 1960s, the Roman landscape – is, like James, unfailingly interesting, whether you agree with it or not.

Which is the other thing I especially liked about this book – there’s space for the reader to walk around in it, to wonder and ponder along with the characters. You finish the book at once moved by the predicament of these characters – “We’re at an age when we must take care not to be embarrassing,” Miranda observes – and with the refreshing impression that your brain has been rinsed.

Marc Levinson, author of "The Great A&P and the Struggle for Small Business in America" (Hill and Wang)

"Liberty's Exiles," by Maya Jasanoff (Knopf)

History, it is said, is written by the winners, and the history of the American Revolution is a textbook example. Jasanoff's engrossing book upends much of what we thought we knew about our country's war for independence. The Revolution, she shows, was not just a war against England but a civil war, tearing apart families and displacing large numbers of people who considered themselves every bit as American as those who favored independence. Jasanoff brings us face to face with Americans whose lives were turned upside down when they were forced into exile and then written out of history. This book is a model of thorough research and writing that is at once careful and vivid.

Will Boast, author of "Power Ballads" (University of Iowa Press)

"Salvage the Bones," by Jesmyn Ward (Bloomsbury)

As Jesmyn Ward’s novel "Salvage the Bones" won this year’s National Book Award, you probably don’t need me to tell you to go out and read it. Nevertheless, go out and read it! The fictional town where Ward’s characters live their fierce, isolated lives is called Bois Sauvage — savage wood — which might begin to give you a sense of the fearsome, unrelenting pace of this book. Men battle men, dogs battle dogs, and nature flattens all of them. At the same, there are beautiful moments of ease, contentment, and peace. (A lengthy description of the pleasures of a fresh squirrel sandwich with plenty of hot sauce comes to mind.) Standing at the center of this world are the narrator, Esch, who’s fourteen and pregnant, and her brother Skeetah, a dogfight entrepreneur (and a dog lover), a protector, and, simply put, a hell of a character. Hurricanes and dog fights aside, "Salvage the Bones" is most of all a complex and savage family story. There’s a good deal of violence in this book, yes, but still more love and loyalty.

I would be remiss if I didn’t also mention Alan Heathcock’s "Volt," one of the best story collections to come along in a while. Heathcock’s narratives are strangely and beautifully structured, and his prose is diamond-cut.

Melissa Fay Greene, author of "No Biking in the House Without a Helmet" (FSG)

"Comedy in a Minor Key," by Hans Keilson (FSG) [published late 2010]

A slender, quietly devastating novel — "Comedy in a Minor Key," by Hans Keilson — might have been missed entirely by the English-speaking world, had not Farrar, Straus & Giroux published it last November in the U.S. in a spare and clean translation from the German by Damion Searls. First published in 1947, it tells the story of a young, recently married, blue-collar couple, Marie and Wim, who take in a secret “guest” during the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands. A 40-year-old perfume salesman, who gives his name as “Nico,” he is a kind and educated man, black-haired and angular, sallow of skin, with few possessions. He moves into the spare upstairs bedroom of their small house and spends long solitary days teaching himself English and French or playing both sides of a chess board. Sometimes he stands quietly hidden behind the curtains, trying to peek at an outside world now denied him. In the evenings, he descends to join the young couple at the dinner table. Standing at the kitchen counter afterwards, drying the plates while Marie washes up, is one of the pleasant moments of Nico’s day. But waiting at the top of the narrow staircase for Marie to bring him the afternoon newspaper, on a day that she has run late with her errands, opens a gulf of longing and despair in him.

At night the young husband and wife whisper to each other their thoughts. Wim rather wishes that he were the older man and Nico the younger, so he would be wiser in the preservation of this threatened life. Marie wonders what it is that makes “their Nico” a Jew. They try to guess who — among their friends, neighbors, local police officers, and the milkman — are “good” and would not denounce them if their secret were discovered.

The action unfolds almost entirely inside the tidy little house, among three people circling one another warily at first and then with growing respect and empathy. All acts of “patriotism,” of “civil disobedience,” take the form of tea, porridge, pajamas, laundry, and the occasional humorous remark. So I can’t resist saying that "Comedy in a Minor Key" stands tall in the tradition of the masterpieces of 17th-century Dutch painting, the interiors and portraits that paid breathtakingly close attention to the quality of light, furnishings, dinner plates, character, and mood.

And why “Comedy”? Comedy, Marie feels, is like a play “where you expect the hero to emerge onstage, bringing resolution, from the right. And out he comes from the left.” The resolution of their sheltering of Nico turns out differently than Wim and Marie expect. One surprise ending is followed by another until everything that was clear at the start goes topsy-turvy.

The author, a German-Jewish doctor and writer, fled from Germany in 1936. He spent the war years first as part of the Dutch underground and then in hiding, though his beloved parents were deported. This book is dedicated to “Leo and Suus, in Delft,” the Dutch couple who hid Keilson. After the war, he stayed in the Netherlands, became a psychoanalyst, and did pioneering work with war-traumatized children. A centenarian, Keilson died this past May, a gifted child psychologist, a brilliant writer, and a man who understood what it meant to be “good.”

Wendy McClure, author of "The Wilder Life: My Adventures in the Lost World of Little House on the Prairie" (Riverhead)

"In Zanesville," by Jo Ann Beard (Little, Brown)

"In Zanesville" by Jo Ann Beard was one of the most deeply pleasurable reads I’ve had in recent memory. It captures the sheer anarchy of being a 14-year-old girl like no other novel I’ve ever read: this almost feral and often very funny world of surreal slumber parties and babysitting gigs, and a wonderfully astute portrayal of friendship at the center of it all.

Emma Straub, author of "Other People We Married" (FiveChapters Books)

"The Stranger's Child," by Alan Hollinghurst (Knopf)

"The Stranger's Child" is a book about memory, and secrets, and literary legacies. It is a romance, a history of romance, a history of a history. The book's careful, measured pace allows time to do its worst to Hollinghurst's characters, and I was astonished at where some of them ended up. My experience reading "The Stranger’s Child" had similarities with my experience reading my favorite book of last year, Jennifer Egan’s "A Visit from the Goon Squad" — in both cases, it took me a few chapters to realize exactly what I was in for. After the second chapter of "A Stranger’s Child," I wanted to absorb the novel directly into my blood stream. It is precisely the sort of novel that, the moment you finish it, you flip it back to the first page, and begin again.

Alethea Black, author of "I Knew You'd Be Lovely" (Broadway Books)

"You Think That's Bad," by Jim Shepard (Knopf)

Reading a great book can sometimes answer a question we didn’t even realize we were asking. At the end of “Low-Hanging Fruit,” a story in Jim Shepard’s extravagantly inventive new collection "You Think That’s Bad," a particle physicist is about to leave home to go work in Geneva. “'What are you really looking for?’ my wife said to me, last thing, before I left. What we’re all looking for. That saving thing, I think: something that right now is beyond our ability to even imagine.” But there seems to be absolutely nothing beyond the imagination of Jim Shepard.

Shepard, who has written six novels and three previous collections, the most recent of which won the 2007 Story Prize, possesses a wildness of mind you might expect to see among geniuses, convicts, and madmen. His stories drop you into worlds ostensibly alien — the Arabian desert in the 1930s, the Netherlands of the future, the French aristocracy of the 1430s — but emotionally familiar. "You Think That’s Bad" displays all the classic Shepardian gifts: it’s ingenious, pitch-perfect, and breathtakingly researched (his Acknowledgments page could double as a bibliography); what surprises us is its depth of heart. Here’s a moment from a story about the creator of Godzilla: “He said he was weeping for all that he’d been granted, and for everything he’d thrown away …." Even villains turn out to be capable of moving self-revelations: “All I desired, morning in and evening out, was a love with its arms thrown wide,” says the narrator of the most gruesome piece in the collection. And one story, “Happy with Crocodiles,” portrays the brutal senselessness of combat so vividly that after reading it I was too agitated to sleep.

But Shepard also kept me up laughing. There’s nothing like reading a book while the person beside you tries to sleep to show you that struggling to suppress laughter only makes a bed shake more violently. “If it was some fucking thing no one else wanted to do, I did it,” says the protagonist of my favorite story, “Boys Town,” who has one of the most dead-on voices I’ve ever come across. “I drove a shuttle. That job had a little pin that came with it that said Martin, for Comfort Inn. Whenever I said stuff to my mother like I could see why my dad walked out, she’d go, ‘Where’s your pin? Don’t lose your pin.’” I also loved: “[My father] said the sign over the main gate read ‘We’re Here to Lick Old Man Depression.’ ‘Lick him where?’ he said when my mom quoted it to some friends they had over." And: “While we rode Ismail sang a Kurdish song whose chorus was ‘Because of my love / my liver is like a kabob’."

If there was a book published in 2011 that’s more compulsively readable than "You Think That’s Bad," I certainly didn’t read it. My copy is mottled with red wine stains and chocolate fingerprints because I refused to put it down when it came time to eat.

Daniel Rasmussen, author of "American Uprising: The Untold Story of America's Largest Slave Revolt" (HarperCollins)

"Boomerang: Travels in the New World," by Michael Lewis (W.W. Norton)

Saying that Michael Lewis is the author of your favorite book of the year is a bit like saying that Wayne Gretzky is your favorite hockey player or that U2 is your favorite band. The choice is so appallingly popular as to arouse the suspicions of literary insiders who wonder if you’ve even heard of Chad Harbach.

But Lewis’s new book, "Boomerang: Travels in the New World," resonates with me not simply because of Lewis’ deft prose, gift for colorful anecdote, or general mastery of the art of nonfiction storytelling, but because of the questions his book raises about the future of the United States – questions that matter especially to 20-somethings like me.

As I read "Boomerang," I grew increasingly worried about the cultural and political impacts of high debt balances and meager growth. His brilliant portraits of Greece and Ireland and Iceland, trapped by debt and weighed down by pessimism, made me fear a similar outcome here in the United States, where our persistent deficits have led to a debt-to-GDP ratio that is already higher than the European Union’s.

Lewis frames our global economic malaise with a lighthearted grace free from the bitter partisanship that represents our greatest obstacle to achieving meaningful reform. And he is the rare writer who can turn the banalities of the dismal science into a book with mass appeal. Lewis’ writing – and this book – may already be popular, but I know the solutions to the problems he describes will not be. I just hope more people read this book to understand just what will happen if we don’t make those unpopular choices sooner rather than later.

Josh Rolnick, author of "Pulp and Paper" (University of Iowa Press)

"The Cat's Table," by Michael Ondaatje (Knopf)

When I read Michael Ondaatje’s short story “The Cat’s Table” in The New Yorker in May, I secretly hoped it was not part of a larger novel. The story felt perfect, a complete movement. And I’ve been let down at times when such stories, small treasures, later unspool into less powerful novels. Or else, also a risk: The novel overpowers the story, rendering it a mere excerpt.

What a thrill, then, to read this lustrous novel, one that shines just as brightly, while leaving the original undiminished – a candle, lit from a match.

The novel is the story of Michael, 11, and his journey aboard the ocean liner Oronsay from Colombo, Sri Lanka (then Ceylon), to Tilbury, England, in 1954 to meet his mother, whom he has not seen for more than three years. Michael dines at the “cat’s table” – a derisive twist on the Captain’s Table – with a cast of characters so insignificant, so low in stature and class, they are all but invisible to their fellow seafarers. It’s a cloak, however, that gives Michael and his tablemates, the quiet Ramadhin and the scornful Cassius, free rein to explore. They soon discover a fantastic, ayurvedic garden growing deep in the ship’s hold; an enthralling Australian roller-skater who appears each day before dawn; and the menacing Hyderabad Mind, a circus performer from the Jankla Troupe with ghoulish, terrifying eyes. They sleuth details about a philanthropist, bitten by a rabid dog, traveling to England for a cure, and also a shadowy criminal, who appears each night, manacled, for his prisoner’s walk on deck. All the while he is watched over by Emily de Saram, a distant cousin who just happens to be on the ship. Beautiful and brave, older and more worldly, Emily awakens in him tender, wrenching feelings he can’t begin to explain.

“I stayed with her all morning,” Michael relates. “I do not know why I was confused about things. I was eleven. One doesn’t know much then.”

Eventually, the narrative dips and weaves between the Oronsay and Michael’s life years later as a successful expatriate writer in North America, and we come to understand the novel through juxtaposition: the naïve boy who feels safe in his bunk at night, surrounded by whispering card-players, and the wiser middle-aged man who has lost a dear friend and ruined his marriage.

Oftentimes, both appear in the same sentence: “Her other hand was still gripping mine as no one had ever done,” Michael says of Emily, on board the Oronsay, “convincing me of a security that probably did not exist.”

This, in the end, is what the novel comes to be about: the ephemeral nature of safety, itself.

And as the father of three boys – my oldest four years younger than Michael – this is where, on the lower frequencies, the novel speaks for me.

“I don’t think you can love me into safety,” Emily tells Michael when they are grown.

He can’t. But of course, neither can we.

Michael Holroyd, author of "A Book of Secrets: Illegitimate Daughters, Absent Fathers" (FSG)

"How to Live: A Life of Montaigne in One Question and Twenty Attempts at an Answer," by Sarah Bakewell (Other Press) [published late 2010]

A book I greatly admired and enjoyed this year is Sarah Bakewell’s "How to Live: A Life of Montaigne in One Question and Twenty Attempts at an Answer." This most original set of “conversations” is a perfect vehicle for carrying the reader back into the 16th century and then bringing Montaigne into our own contemporary world. He appeals to us, and his writings are needed by us, because, as Lytton Strachey explained a hundred years ago in his "Landmarks in French Literature," “Montaigne stands out as one of the earliest of the opponents of fanaticism and the apostles of toleration.” He is a writer of everyday life and his is a modern voice. His charming, garrulous, confidential essays, covering all aspects of his character, tastes, habits and opinions, bring us directly into the presence of this fascinating man. And this is Sarah Bakewell’s achievement. She gives his engaging Essays on anything and everything a pattern that they otherwise lack and she conveys a sense of being with a long-dead writer who is very much alive. This is the ideal of all critics and biographers.

Jon Ronson, author of "The Psychopath Test: A Journey Through the Madness Industry" (Riverhead)

"A Visit From the Goon Squad," by Jennifer Egan (Random House)

My choice is "A Visit From the Goon Squad" by Jennifer Egan [released in the U.K. in 2011]. ... It's really compelling and original and funny, a puzzle book zipping back and forward across the decades about why lives fall apart. Sasha the kleptomaniac was my favorite. I was desperate to know how she ended up that way, and whether things would turn out OK for her. It's rich and rewarding with amazingly funny set pieces, especially the story about the P.R. woman who gets involved with a dictator. It's a great book. I downloaded Egan's "Look At Me" on the Kindle straight afterward but haven't read it yet.

Shares