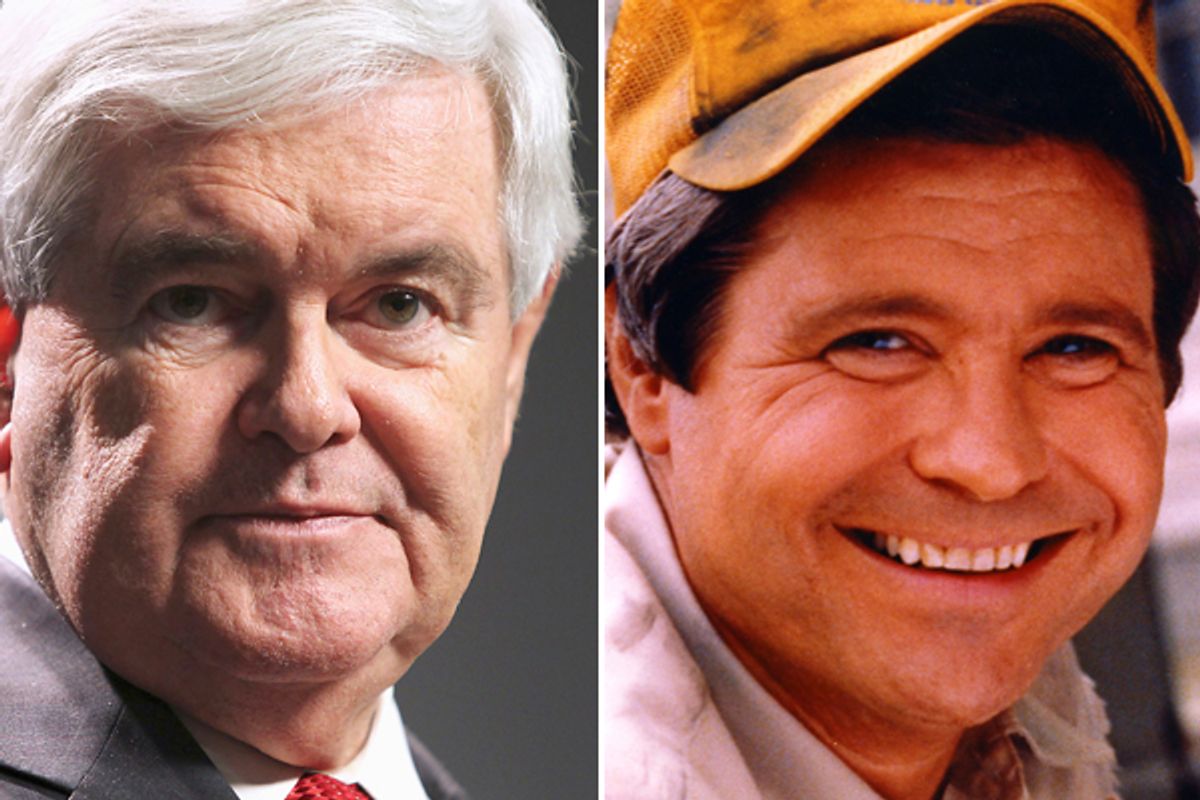

His 1994 reelection campaign in Georgia's 6th District may have been the only time in Newt Gingrich's congressional career that he faced an opponent with a funnier-sounding first name: Cooter. That's how most red-blooded Southerners knew Ben L. Jones, who played the good 'ol boy mechanic Cooter Davenport on the CBS series "The Dukes of Hazzard" before entering politics.

At the time, the Newt-Cooter contest barely registered on the national radar. Redistricting had turned Georgia's 6th District into a GOP bastion, and the '94 political climate -- across the country but particularly in the South -- was poisonous for just about anyone bearing the Democratic label. But Jones, who was walloped by nearly 30 points and has since relocated to rural Virginia, emerged with some firsthand insight into the Gingrich style that, with his old opponent's sudden rise to the top of the GOP presidential pack, has new value and relevance.

"What I was doing, I'm not sure," Jones now says of that campaign. "He was damn near beat (in the early '90s), so in the redistricting he basically worked and drew himself that district. It was a heavily Republican district. But I knew that somebody had to run against him, even if I had two chances – slim and none. But I decided that somebody needed to stand in front of the freight train."

Actually, Jones was familiar with his opponent even before the race started. After "The Dukes" ended its run in 1985, he pivoted to politics, running the next year as a conservative Democrat and nearly ousting Republican Rep. Pat Swindall in Georgia's old 4th District. Encouraged by the near-miss, Jones tried again in 1988, this time coasting after Swindall was indicted for perjury before the election. For the next four years on Capitol Hill, Jones was a bystander as Gingrich -- then the only Republican from the state's delegation -- completed his rise from gadfly backbencher to de facto Republican leader.

While Gingrich successfully built a loyal following of conservative partisan warriors and maneuvered his way toward power, Jones says he was struck by the lack of a human touch.

"I used to go down to the House gym and play basketball," he recalls. "It was the greatest bipartisan thing. Your politics didn't matter. Everybody was just pals -- you know, right-wing, left-wing, Democrat, Republican. We were just out there playing basketball and sharing some fellowship and burning some anger off and getting to know each other. And it was a very real thing. I made a lot of friends, and still see them all over the country sometimes. But Newt was never there. He was not there. He never showed his face in that place -- because he was conspiring."

One of the key moments in Gingrich's ascent came in 1989, when he led a successful effort to dethrone House Speaker Jim Wright, who had skirted House limits on speaking fees by having some groups he addressed make bulk purchases of his book. Jones says he was galled by his fellow Georgian's hypocrisy, since Gingrich had been enmeshed in a book controversy of his own and his own fundraising activities as the head of a conservative political action committee (GOPAC) had also been questioned.

“Gingrich went after Jim Wright on a book that Jim had written, and the Teamsters or some union had bought a bunch of the books. Now, that’s what Gingrich does for a living, right? But he made it seem like the worst thing and stirred it up and stayed on it, and Jim just finally said, ‘The hell with it” and quit. So Gingrich had achieved a major thing by destroying Jim Wright over what was an infraction – but it wasn’t anything compared to what Gingrich was doing. But he got him.”

The Wright campaign, Jones says, helped convince him that Gingrich was “a great demagogue. He has the ability to fire people up and appeal to the worst in them.”

In 1990, Gingrich suffered an unexpected close call in his reelection race, holding off an unknown and underfunded Democrat by just 900 votes. Jones was reelected in his own district, but when the lines were redrawn for 1992 his was erased from the map -- while Gingrich's was transformed into a Republican haven. Jones sat out the '92 race (surgery that led to staph infection played a role) but two years later was ready for a comeback bid, and without many Republican targets around, he settled on a match against Gingrich.

By then, Gingrich was the House GOP leader-in-waiting, having secured the necessary commitments to replace Robert Michel, who was retiring after the 1994 election. Now in a seemingly safe district and with his party positioned for sizable gains nationally, Gingrich wanted nothing to do with Jones, and looked for excuses to duck him.

"I forget exactly why, but he misused a word once in an interview and called me ‘scurrilous,'" Jones recounts. "Now, what scurrilous really means is profane – someone who curses. So I came out of some event and there was a reporter from the Atlanta Constitution. And the guy says, ‘What do you think about Newt Gingrich calling you scurrilous?' And I said, ‘Aw, f--- him and the horse he rode in on.’ And the guy laughed, but there was a guy there too from the alternative paper, and he printed it. And then Gingrich said, ‘I’m not going to debate this man! He says things you can’t print in a family newspaper!’ And he demanded an apology. So I said, ‘I tell you what: I’ll apologize to your horse right now and I’ll apologize to you when I see you at the debate.”

But when a public television station scheduled a debate, Gingrich was a no-show, leaving Jones to square off against an empty lectern. To generate attention, Jones decided to follow Gingrich around the country, crashing speeches and fundraisers in Wisconsin, Connecticut and Alabama and trying in vain to force a confrontation with his opponent. At one point, he even brought a set of bloodhounds along to aid the search.

“I didn’t see much of him, but we had fun," says Jones.

When Gingrich's 28-point victory became official on Election Night, he was already in Washington celebrating his party's stunning midterm triumph: a gain of more than 50 House seats, handing Republicans control of the House for the first time in 40 years -- and making Gingrich the new speaker. But, in a roundabout way, Jones got the last laugh.

"Two things happened," he explains. "One is that he beat the hell out of me. The other, though, is that during the course of that campaign, my attention was brought to the Georgia Public Records Act, and a whole pile of documentation that showed Gingrich had funneled non-taxable money for an education project he had and used it for political purposes."

In the campaign, Gingrich ignored Jones' attacks, but Democrats in Washington took notice, and Jones' research formed the backbone of an ethics scandal that would haunt Gingrich's speakership, ultimately leading his colleagues to vote 395-28 to reprimand and fine him $300,000 in January 1997. Months after that rebuke, Gingrich barely staved off an intraparty coup, and when the GOP suffered unprecedented losses in the 1998 midterms, he stepped down as speaker and left the House -- with a shove from his fellow Republicans.

“I felt like in some ways he won the battle but I won the war," says Jones, who notes that Gingrich is still "commingling" his political and personal interests to this day.

“He does it gaming the system. You look at his stuff at GOPAC, and that was just the beginning. That was just the foundation of his complex activities. And they’re mostly all related to changing the policy of the federal government to the way his donors want it to be. He sells these books and makes these videos and gives these talks and has these little plaques that he gives out – and he makes money off it. And he’s the one who complains about Washington being the problem and all of that insider stuff, and yet that’s what he does.”

Jones says he's as shocked as anyone by Gingrich's surge to the top of the Republican presidential pack. He detects a subtle stylistic evolution, something that became clear to him while watching Gingrich resist conflict with his opponents in this year's GOP debates and instead patiently wait his turn.

"That’s a lot smarter than he used to be," says Jones. "He was thin-skinned and always on the attack, and carried grudges. I see a little difference there. Now, that means rather than acting like he’s 14 years old, he’s acting like he’s 19 years old.”

He adds: “Newt, unlike anybody else I’ve ever know – and I’ve known presidents of the United States, and foreign potentates, and real big-shot movie producers and actors. Newt is the only one who I thought really considered himself to be an important world figure – a transformative sort of historical figure. I mean, he has that image of himself.”

Jones now expects his one-time foe to be Barack Obama's opponent, a prospect that excites him. “If anything is ever going to galvanize the Democratic Party, which is somewhat dispirited at this point, it would be a Newt Gingrich candidacy," he says.

And if the White House asks for a scouting report?

“The only advice I would give is: Do not take him lightly. Out-work him, out-talk him, go at him, challenge him to debates all over the country.”

Shares