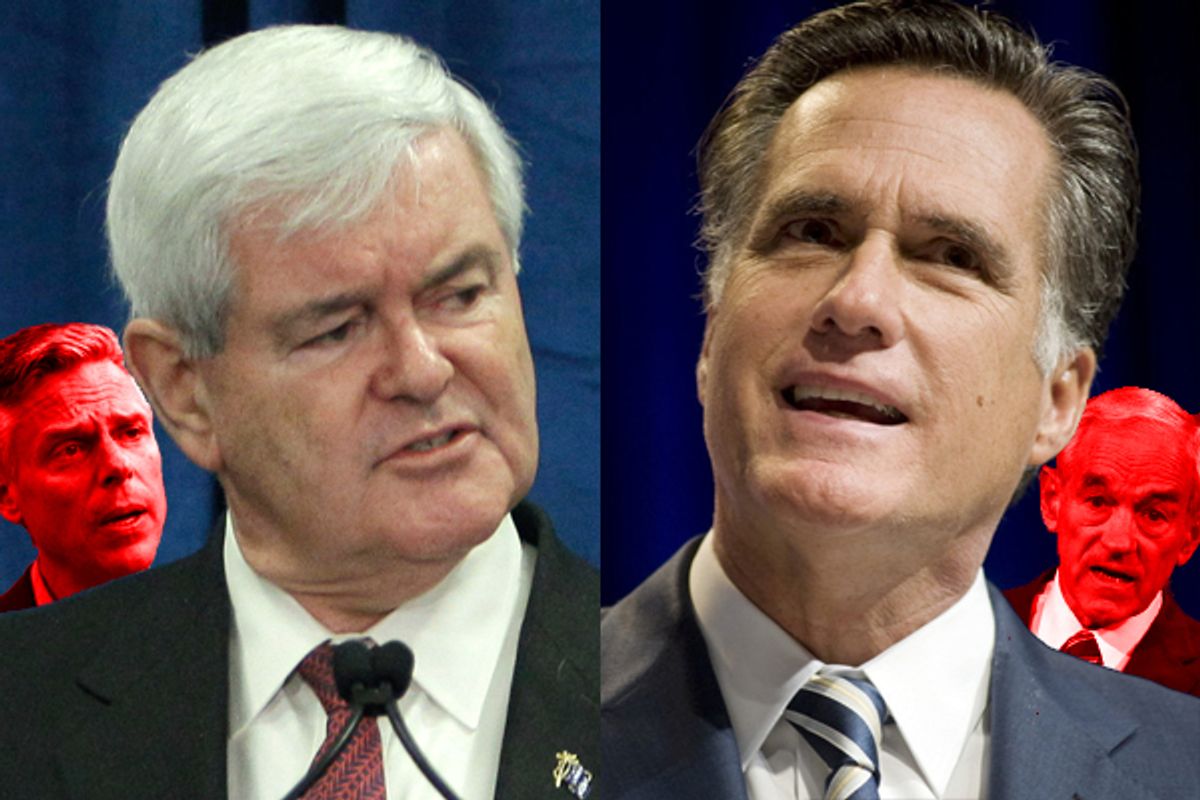

It’s not inaccurate to say that the Republican presidential race seems to have evolved into a contest between Newt Gingrich and Mitt Romney.

After all, Gingrich has emerged as the clear leader in national polls and in the three of the four key early states, while Romney generally finishes second in those same surveys and remains the front-runner in New Hampshire. Plus, in a break with what happened when other Romney alternatives surged to the front of the GOP pack this year, polls now show that Gingrich’s supporters largely consider Romney their second choice. In other words, if Newt falters like Herman Cain, Rick Perry and Michele Bachmann all did before him, Romney finally seems in position to claim his fleeing backers and gallop away with the nomination.

But that doesn’t mean the GOP contest is now a one-on-one fight -- not with the tag-team season suddenly upon us. If you remember the 2008 campaign, you know how this works: Two front-runners emerge, giving rise to opportunities for alliances of mutual interest with desperate non-front-runners.

In the Republican race last time around, we saw this happen when Romney and John McCain found themselves positioned as the two most plausible nominees. Romney, who was running hard to McCain’s right and had led in Iowa and New Hampshire for most of the year, seemed to have the inside track. If he could win Iowa, then surely he’d prevail in New Hampshire, and from there it would be a roll.

But by December ’07, McCain was surging, a remarkable recovery from just months earlier, when his campaign had seemed dead. He had a real chance to knock off Romney in New Hampshire – but only if Romney first took a hit in Iowa, a state McCain wasn’t aggressively contesting. Fortunately for McCain, though, Mike Huckabee, with his strong appeal to Christian conservatives, was playing hard in Iowa and had the potential to embarrass Romney there.

Thus did McCain have strong incentive to lavish public praise on Huckabee, refrain from attacking him, and back him in any public dispute with Romney – just as Huckabee had every incentive to side with McCain every time Romney went after him. This was the dynamic that defined most Republican debates in late 2007 and early 2008, and it worked perfectly for the two teammates. Huckabee got the Iowa win that made him a national player, which gave McCain the opening he needed to push ahead of Romney in New Hampshire, then finish him off in South Carolina and Florida.

This time, two Republican tag-teams seem to be forming – and both were on display Monday.

The first involves Gingrich and Jon Huntsman, who shared the stage in New Hampshire for what was billed as a Lincoln-Douglas-style debate on foreign policy. But the session was marked by mutual flattery and an utter lack of conflict – “the friendliest debate of the 2012 season,” NBC’s First Read declared.

Of course it was. Gingrich has absolutely no reason to knuckle up Huntsman, who is concentrating his entire campaign effort on New Hampshire – the only early state where Gingrich now trails Romney. Since he’s targeting the same non-Tea Party crowd that is otherwise most likely to gravitate toward Romney, Huntsman will be doing Gingrich a big favor if he can fare well in the state.

And Huntsman has no reason to punch at Gingrich – at least not yet. Since he’s putting so much on New Hampshire, he needs Romney stagger into the state next month off of a bad Iowa showing. Which means that it’s in Huntsman’s interest for Gingrich to stay strong for the next month, creating an opportunity for Huntsman to finish ahead of Romney in New Hampshire and to emerge as the default candidate of any Republican then looking to stop Gingrich.

The other candidates with aligned interests are Romney and Ron Paul, who is polling far better than he was four years ago and may even have a chance of winning Iowa. From Romney’s standpoint, Paul is the perfect straw to drain votes from Gingrich, whose appeal is rooted in the same Tea Party base that Paul claims as his own. Obviously, Romney would prefer to win Iowa himself, an outcome that might end the GOP race on the spot, so Paul is his friend in the state: The more the Tea Party base is divided between Gingrich and Paul, the better Romney’s prospects are of eking out a victory.

Short of that, the next-best Iowa result for Romney will probably be any Gingrich showing that is deemed unimpressive by the political world. In other words, the damage of (say) a dismal third place finish for Romney could be lessened if Paul were to edge out Gingrich and win the state. Under this scenario, Romney wouldn’t leave the state with any momentum, but neither would Gingrich. And the more viable Paul is in subsequent states, the more damage he’ll presumably do to Gingrich.

The same basic logic applies for Paul. Gingrich has a head of steam right now, but Paul believes the voters who are most attracted to the former Speaker – outsider-obsessed lovers of ideological boldness and purity – should rightly be his. Any Paul strategy depends on Gingrich’s surge being arrested, which explains the scorched earth anti-Newt campaign he’s launched recently.

Last week, the Paul campaign trotted out a brutal viral video that pilloried Gingrich as a serial hypocrite. On Monday, they followed up with an equally devastating one that portrayed Gingrich as venal, access-peddling Washington insider:

These tag-teams will only last as long as the interests of each partner are aligned. And while the McCain/Huckabee example from 2008 shows how effective they can be, another example from that year’s Democratic race offers a cautionary note: Remember how bad it looked when Barack Obama and John Edwards seemed to gang up on Hillary Clinton days before the New Hampshire primary – an event that Clinton miraculously bounced back to win?

Still, the informal Gingrich/Huntsman and Romney/Paul alliances are a reminder that even when there seem to be two clear-front-runners, every candidate is worth paying attention to.

Shares