He has clearly expanded his support from 2008, is basking in some enviable press coverage, could very plausibly win Iowa, and has a credible strategy to gobble up delegates in subsequent caucuses, but if you need further proof that Ron Paul is starting to make Republican elites uneasy, here's Exhibit A: Sean Hannity went after him hard on Wednesday night.

Hannity's shtick is to be the GOP's cheerleader-in-chief, relentlessly pressing anti-Obama talking points while puffing up any Republican who's willing to read from the script. Thus, he's spent the current campaign presenting every major Republican candidate in a flattering light and telling his audience that each is equally capable of taking down Barack Obama -- except for Paul, whose non-interventionist foreign policy views and warnings about blowback are fundamentally at odds with the virtual merger of GOP and Likud politics.

Hannity's preferred strategy has been to ignore Paul, so it's telling that less than three weeks before the Iowa caucuses he felt the need on Wednesday to bring Bill Bennett on his show for a segment of unsaturated Paul-bashing. Bennett articulated an increasingly common concern among GOP elites, saying that Paul's candidacy "isn’t going anywhere -- except if he wins Iowa."

And what happens if he does?

If you have a mischievous streak, it's a fun possibility to consider, because the short answer is that guys like Bennett and Hannity will freak out -- and their freak-out could last for a while. An Iowa victory would make Paul the center of the political media world, flood his campaign treasury with even more small-dollar donations, and boost his prospects in subsequent states. He might be able to parlay it into an impressive showing in libertarian-friendly New Hampshire, weather losses in South Carolina and Florida (where the numbers just aren't very promising), then surge again in February, when his caucus state strategy kicks in. If the rest of the field remains unsettled then -- with, say, Romney winning New Hampshire and Newt Gingrich taking South Carolina and Florida -- Paul could find himself at or near the top of the delegate race, pushing the Hannity/Bennett panic level through the roof.

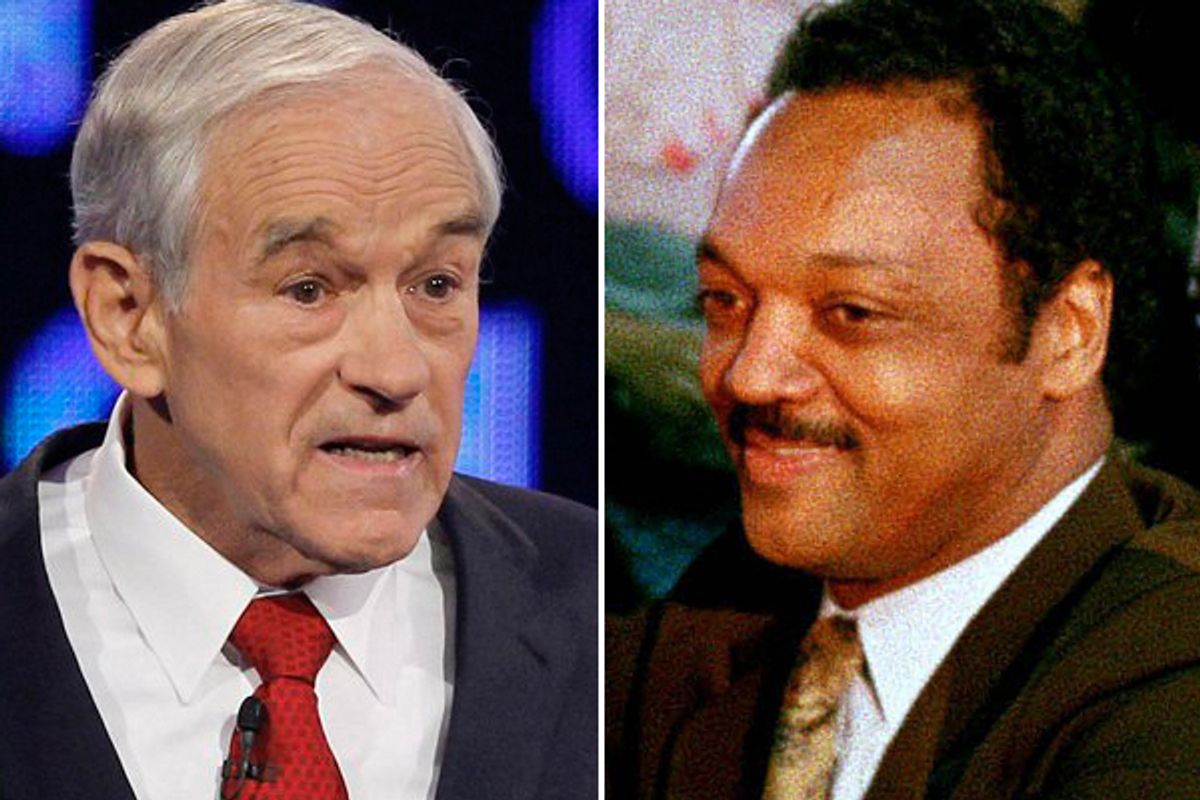

If the scenario I just sketched out sounds vaguely familiar, it's for good reason. It's roughly the story of Jesse Jackson's 1988 campaign for the Democratic nomination. Jonathan Bernstein first made the Paul/Jackson comparison last week, and there's a lot to it. Like Paul, Jackson was a repeat candidate who enjoyed much wider support in his second bid. He was also seen as a niche candidate and was persona non grata to most Democratic leaders, who saw his far-left views (particularly on foreign policy), penchant for controversy ("Hymietown"), and ties to black urban politics as potentially damaging to their party. And, just like Paul, his unfavorable poll scores among his own party's voters tended to be much higher than those of his opponents. So the prevailing assumption was that Jackson faced a unique ceiling in the Democratic race.

But the combination of Jackson's expanded base of support and an unusually volatile Democratic race in '88 led to a moment in the primary season when the party's elites actually believed their worst nightmare might be playing out. It came when Jackson, who skipped Iowa and New Hampshire, essentially fought Michael Dukakis and Al Gore to a three-way tie in the early March Super Tuesday primaries. Jackson won five states that day, and nearly picked off a few more. It was a revelation to the political world, which until then hadn't realized the extent of Jackson's expanded support. More to the point, it put him within spitting distance of the delegate lead.

And then things got really funny. A week later, Dukakis -- who had been seen as the front-runner, albeit a weak one -- was crushed in the Illinois primary, finishing a distant third with just 17 percent. The winner (with 42 percent) was Paul Simon, who represented the state in the Senate but had previously suspended his campaign. Jackson, boosted by his Chicago ties, was next with 32 percent -- far better than he'd been expected to do. Now the press was asking: What's wrong with Dukakis? Why won't Democrats rally around him? Then came Michigan, where Jackson scored a shockingly easy victory over Dukakis -- and took the lead in the national delegate race. Here's how the New York Times described the reaction of party elites:

Democratic Party leaders expressed astonishment today at the Rev. Jesse Jackson's landslide victory in the Michigan caucuses Saturday and confessed that they found it hard, after weeks of surprises, to predict how or when the party's Presidential race would be decided.

For the first time, party professionals began actively contemplating the possibility that Mr. Jackson could emerge from the primary season, which ends in California and New Jersey June 7, with the most delegates.

One said that it was ''remotely, barely, distantly conceivable'' that the party might actually end up by nominating Mr. Jackson. Others agreed that outcome was possible but, although they would not say it for attribution, almost none believed that a black candidate can be elected.

This is the moment that could await Republicans in the weeks and months ahead.

Of course, the rest of the Jackson story is instructive, too. The rally-around-Dukakis effort from party elites took on immediate urgency, with Dukakis quickly scoring badly needed wins in Connecticut and Wisconsin, then enduring a brutal, racially divisive fight in New York (thanks, Ed Koch). After his double-digit Empire State win, Dukakis was never threatened by Jackson again and rolled to the nomination with ease. Not that Jackson didn't make the pre-convention months as difficult as possible for them, publicly campaigning for the No. 2 slot on Dukakis' ticket and threatening to upstage Dukakis in Atlanta and on the fall campaign trail.

In the end, Jackson did face a real ceiling on the Democratic side. But it wasn't nearly as low as everyone originally thought it was, and it took an entire primary season to figure out exactly where it was. The same may be true for Paul.

Shares