The circus begins today at 1 o’clock.

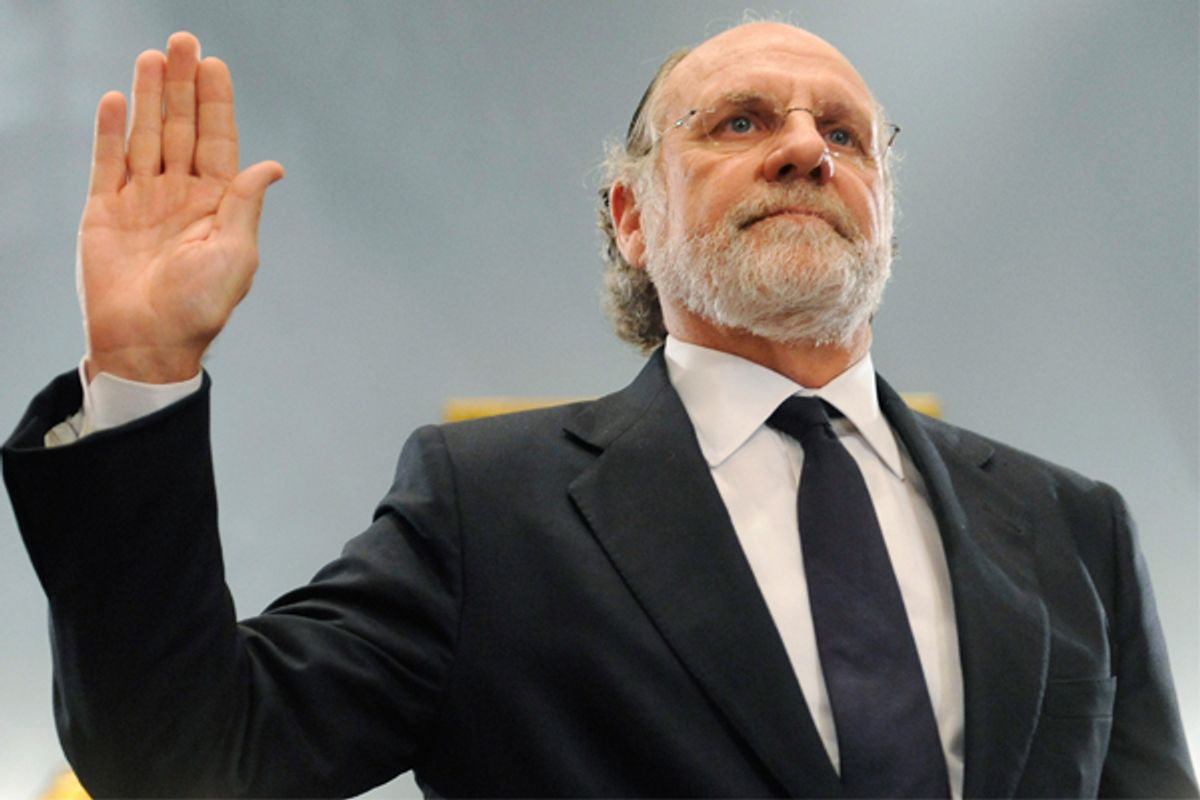

I am, of course, referring to the congressional ritual known as the “no-cost inquisition.” Others will appear, but Jon Corzine is the star attraction. Sometime during the afternoon he will raise his right hand, swear to tell the truth, and then be subjected to impressive cross-examination by the House Financial Services Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations in Washington. Corzine has been to several of these, so he knows he has a role to play.

His job will be to once again explain how MF Global became the Frankenstein of financial scandal, with elements of every financial scandal in recent years (without it being his fault in any kind of punishable way!). He will do his best to show humility, contrition and, above all, lack of scienter. This and the other MF Global hearings are useful exercises, shedding light on a grotesque example of Wall Street run rampant. They are unarguable Good Things. They keep up the decibel level, raise public awareness, and are fine for journalists, prosecutors (for they lock the witnesses into their stories) and any actual regulators out there. It’s a fine thing for Congress to exercise its oversight function, until you consider that no legislation of any value ever seems to emerge from them, because Congress is simply too corrupt and ideologically paralyzed.

When it comes to making laws that protect the public from the financial services industry, Congress has done a progressively worse job since the Pecora Commission hearings of the early 1930s, which led to Congress taking bold steps to regulate banking and securities firms in 1933 and 1934. By the time of Enron in 2001-2002, Congress was hesitant and vacillating. In 2008-2009 it was feeble. Today, with Republican dominance meaning it does literally nothing — except, perhaps, weaken what has already been enacted that impedes Wall Street — it is a joke.

Unlike classic congressional hearings in the past, such as the Watergate or CIA/Contra hearings in the 1970s and 1980s, respectively, the primary purpose of congressional Wall Street hearings in recent years is to provide a cover for congressional inaction. It doesn’t matter who is in the hot seat, Alan Greenspan, Lehman Brothers’ Dick Fuld, or a parade of Bernie Madoff-ignoring regulators. What these processions down the via Dolorosa conceal is that Congress simply isn’t going to do anything about whatever it is told, and that if it does anything, it will be ineffectual, or — as it was throughout the deregulation mania of the Clinton years — worse.

So on with the show! And quite a show it will be, for MF Global is a marvelous, multifaceted scandal, an assemblage of small pieces of just about every financial scandal over the past two decades. Somehow the firm “lost track” of $1.2 billion of client money (shades of Bernie Madoff?), made use of “repurchase agreements” (as in the Salomon Brothers bond trading scandal of the early 1990s) in a fashion that seems to have confounded its management team, board of directors and auditors (as in Enron and the early-aught scandals), perhaps because it was all so darned complicated (as in the Long-Term Capital Management collapse of the late 1990s). It was presided over by a CEO who seems to have been either deeply inattentive, deeply culpable, or simply brain dead (as in all of the above).

What won't be said during the Corzine circus is that each of the above financial fiascoes resulted in congressional hearings and dramatic revelations. The contrast with the 1930s is that dramatic revelations did not lead to dramatic action. Enron and other scandals of that era led to Sarbanes-Oxley, which dealt with criminal fraud not by strengthening regulation of Corporate America but by imposing paperwork requirements. Meanwhile, George W. showed his devotion to securities regulation by appointing anti-regulation corporate lawyer Harvey Pitt to head the Securities and Exchange Commission.

Sarb-Ox was as big a joke as Pitt. Take its approach to ethics. Enron and similar scandals involved deeply unethical corporate executives. Sarb-Ox required public companies to make their ethics codes publicly available, and to grant “waivers” when its top officials wanted to do something unethical. Therefore, unethical behavior (unless there was a waiver) became a kind of backhanded Sarb-Ox violation — or at least it would have been, had that provision of the law ever been enforced, which it never was.

The heart of the 2008 financial crisis was a coterie of reckless financial executives, working for too-big-to-fail financial companies, who were handsomely compensated for taking risks that almost ruined the economy when they failed. Congress could have tackled too-big-to-fail by reinstating Glass-Steagall, the 1932 law that separated commercial and investment banks, which was eroded during the 1990s and finally wiped out by the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act of 1999. Instead of undoing all the damage that it wrought on the financial system in 1999, Congress enacted a watered-down package of reforms and created a Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, which it has since emasculated as Senate Republicans refuse to confirm a director. We’re seeing that battle being played out right now.

Effective legislation is unthinkable for hard-right Republicans, of course, but is problematic for Democrats and Republicans alike because it would jeopardize campaign dollars. According to OpenSecrets.org, which tracks such things, nearly $6.5 million has flowed into the 2012 campaign coffers of House Finance Committee members from finance, insurance and real estate PACs, plus another $3.4 million from individuals in those industries.

For Randy Neugebauer, the Texas Republican who chairs the investigations subcommittee, the top sources of funding for his 2012 reelection campaign are from the insurance, banking, finance, securities and real estate industries. The congressman issued a huffy press release announcing the Corzine subpoena, which was a good thing. But one can reasonably expect that his anger, if any, is unlikely to result in any actual legislation discomfiting the financial services industry. Not if he wants to keep those campaign dollars coming in, or to prevent a skewering from the far right.

It’s a bipartisan circus. Ranking investigations subcommittee Democrat Michael E. Capuano also gets substantial backing from contributors in finance, though not proportionally as much as Neugebauer. But Capuano does not have the stage presence of New York Democrat Gary Ackerman, who I mentioned in my last piece on congressional double-dealing (which he didn’t like very much).

Ackerman won’t be at today’s hearing, which is a shame as he is famous for his performances at no-cost inquisitions, especially his scolding of SEC officials who failed to catch on to the Madoff scandal. When the cameras are turned off, Ackerman does stuff like campaign against a key provision of Dodd-Frank, as I described in my last piece, or vote in favor of Gramm-Leach-Bliley.

That’s what makes the no-cost inquisition a thing of beauty. CEOs and regulators don’t care if they’re yelled at. The regulators will resume business as usual, the CEOs will cook up new schemes, and the campaign contributions will continue to flow, just as they did after Ackerman tongue-lashed regulators in 2009. In the 2009-2010 election cycle, his take from finance, industry and real estate interests (see the bar chart here) totaled $283,000, dwarfing every other industry sector financing his campaign. Ackerman's biggest campaign contributors in the 2012 cycle are the good people at Bank of America, corporate parent of Merrill Lynch — thanks to Glass-Steagall repeal. Finance, insurance and real estate contributors are the biggest sources of financing for Ackerman’s 2012 reelection campaign.

What could Congress actually do to prevent future MF Globals? I don’t need to subpoena anyone to come up with the solution, because it’s been evident for years: ditch the failed system of self-regulation that allows scandals like MF Global to take place time and time again. Reinstate Glass-Steagall. Ditch FINRA, the financial industry’s self-regulatory body. Put some backbone in the existing regulatory agencies, the Commodity Futures Trading Commission and the SEC, by boosting their funding, forcing them to stop “no fault” consent decrees, and replacing their industry-captured leadership. Better still, toss out the whole regulatory apparatus and start afresh, just as Congress did in 1933 and 1934, when it enacted a regulatory framework that didn’t previously exist.

None of that is going to happen when Congress prefers spectacle to substance.

Shares