During the presidential campaign, Mitt Romney has lashed out at the Obama administration's taxpayer subsidized grants to clean energy start-up companies. “The U.S. government shouldn’t be playing venture capitalist,” wrote Romney in October. “The very process invites cronyism and outright corruption.” But public records show that Romney's private equity firm, Bain Capital, repeatedly persuaded the government to play venture capitalist when it came to its own portfolio of companies.

News outlets have recently focused attention on Romney’s history as a businessman at Bain, which he founded in 1984. What hasn’t been reported, or fully explained by the candidate, is how Romney often got ahead in the private sector by using government help.

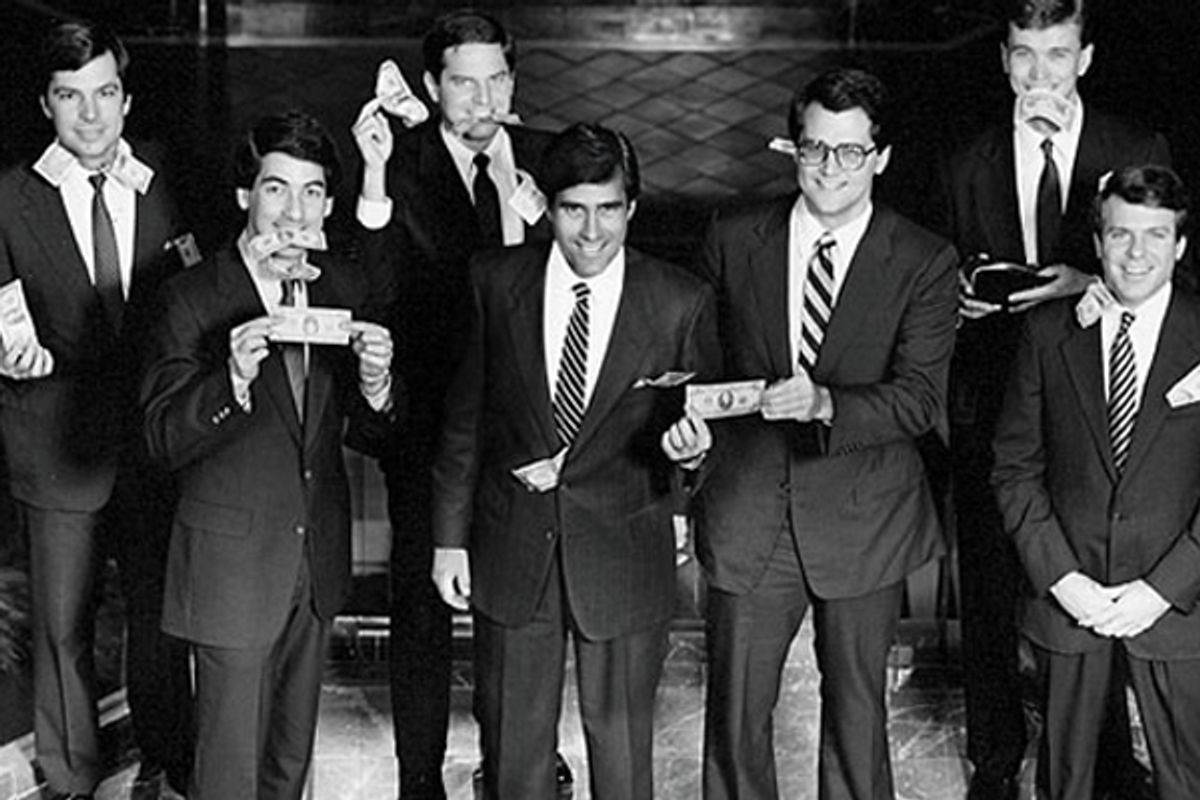

The likely GOP nominee made much of his estimated $250 million fortune buying companies, reorganizing them, and selling them for a profit. Though Romney, whose only government experience is his one term as Massachusetts governor, is quick to claim that he turned around investments using sound management and data-driven strategies, he does not mention one aspect of his success. Bain Capital owned companies that padded their profits using millions in public subsidies. In other cases, firms owned by Bain employed K Street lobbying firms to pursue lucrative government programs.

Consider two of Romney’s first major investments: office supply company Staples Inc. and photo album manufacturer Holson Co. Both persuaded state officials to subsidize their growth.

Shortly after Bain took control of Holson in 1987, executives pushed for the company to expand in the South. Officials from the firm had negotiated with Gov. Carroll Campbell, a Republican, to extend $200,000 in utility support for a new Holson plant in the city of Gaffney. The local city council also approved a $5 million bond for construction, after meeting with representatives from Holson. Five years after South Carolina’s taxpayers had helped finance the factory, Bain chose to sell Holson’s Gaffney facility for $2.8 million. Romney's firm reaped the profits on the taxpayers' expenditure.

The history of Staples, a company that Bain grew from a single store, is a hallmark of the Romney record. Staples’ rapid growth, however, drew on substantial state subsidies.

In 1996, Tom Stemberg, a close Romney business partner leading Staples, met with Maryland Gov. Parris Glendening, a Democrat, to negotiate a package of taxpayer sweeteners to build a new distribution center in Hagerstown. The Glendening administration, using a “Sunny Day” fund of discretionary development money, awarded Staples $2.3 million in grants and low interest loans. The following year, as Glendening prepared for his reelection campaign, top Staples executives maxed out in donations. Stemberg and his colleagues gave a total of $16,000.

A similar story played out in Connecticut, where Staples landed a deal in which taxpayers subsidized over $6 million in low-interest loans for the company to construct a distribution center in Killingly in 1998.

Tapping Washington

The federal government also played a pivotal role in Romney’s ascendant path through corporate America.

GS Industries, a steel company purchased by Bain in the early '90s, faced fiscal problems as Bain withdrew large dividends and management fees. Under Bain’s leadership, the steelmaker hired the K Street lobbying firm of Wiley Rein to seek government support. In 1998-99 the firm paid $140,000 for a lobbying team that included former Democratic Rep. Jim Slattery. GS Industries eventually won a federal loan guarantee, but before the loan could be delivered, the company fell to bankruptcy in 2001. Bain’s executives still made $50 million from their involvement with the firm.

In 1999, Romney departed Bain to take over as the chief executive officer of the Salt Lake City Winter Olympics. The experience, turning an organization in disarray and deeply in the red into a popular event that actually earned over $100 million in profits, is portrayed as yet another example of the candidate’s private sector management skills. Yet the turnaround was achieved in part through the use of professional influence peddling. Under Romney’s management, the Olympic organizing committee spent over $3.3 million on Beltway lobbyists to secure federal funding for the 2004 Winter games.

Olympics lobbyists from firms like Patton Boggs and King & Spalding helped secure federal grants for communications equipment, educational money and public transportation. Millions of dollars were procured from federal officials, who wanted to allay safety concerns in the aftermath of 9/11.

As the New York Times reported earlier this week, Romney’s has continued to earn a windfall from Bain. When he left the firm, he signed a severance package that allowed him to share in the company’s profits in perpetuity. The arrangement might come back to haunt the candidate, given Bain’s increased reliance on lobbyists over the last five years.

Starting in 2007, Bain Capital began retaining various lobbying firms to pressure lawmakers to keep open a loophole that allows much of the earnings by private equity managers to be taxed as capital gains rather than the top income bracket of 35 percent. Given Romney’s profit-sharing retirement deal, the campaign to extend the loophole, which still hasn’t been closed, likely boosted the candidate’s fortune. (Romney has refused to release his tax return, leaving questions about his income.)

As Romney pillories Obama for using the government to fix problems in society (health reform, the auto bailout, etc.), he invites a closer examination of his own career. A balanced view of the Romney record shows he has never had any qualms about government help when it came to his own bottom line. Whether through hiring insider lobbyists or funneling taxpayer subsidies to his companies, government assistance has been part and parcel to the rise of Romney.

Shares