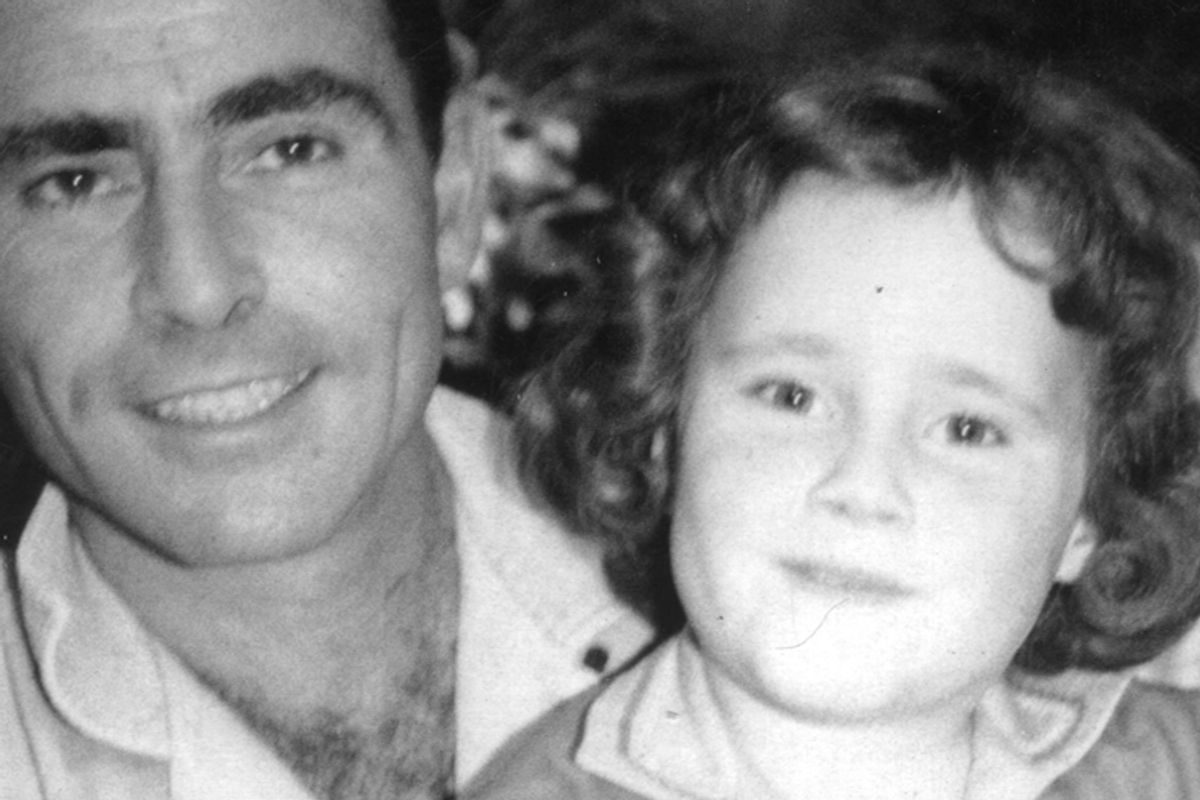

The last time I saw my father, he was lying in a hospital bed in a room with bright green and yellow walls, inappropriate colors intended to console the sick, the dying. As he slept, curled beneath a sheet, I watched him breathe, willing him to, his face still tan against that pillow so white. And as I sat looking at him, I thought of how, when I was small, I would wake in my room beside my flowered wallpaper and listen for his footsteps down the hall, comfortable in their familiarity, secure in the insular world of my childhood, knowing without question or doubt that when I followed those sounds, I would always find him.

When he first got sick, I wiped his forehead dry until he became too ill and I could do nothing, and on the eighth floor of Strong Memorial Hospital in Rochester, N.Y., my father died. He was just 50 years old, I barely 20.

- - - - - - - - - -

In 1975, open heart surgery was new, but we believed the operation was the answer. My father told me that himself. “Pops,” he’d said, calling me by my nickname, “I think this surgery will fix things.” For a moment, we were quiet, the brown of his eyes reflecting my own. I never admitted hearing him tell the doctor, “My survival chances were better in the war.” Deep down, in a place I didn’t want to glimpse, was a fear as immeasurable as his.

A few nights before, he jokingly told us that he had listened to the radio to see what his condition really was, what the doctors, my mother, sister and I might not be telling him. My father was well-known as the creator of “The Twilight Zone” and so the impending surgery had reached the media. I thought of him, lying in that hospital bed beneath the thin blue blanket, listening for his status update, the heart monitors attached to his chest, that, when I was there, he pretended were microphones. He swore into them and then launched into a litany of dirty limericks: “There once was a laddie from Boston ...” These always made me laugh.

On the night before his surgery, the moon was full, a white-yellow glow pouring through the hospital window, illuminating him. We kissed him goodnight and said we’d see him tomorrow.

As the next day moved forward, people -- faceless forms in the hospital waiting room -- drifted in and out. Seats were filled and then emptied, like a child’s game of musical chairs. Doctors and nurses hurried down halls, white coats flowing behind them, their soft-soled shoes silent against the tiled floor. Elevator doors opened and closed, telephones rang, announcements echoed paging doctors, and we paced, keeping step with strangers’ ankles, waiting for news.

I was in the hospital hall leaning over the drinking fountain when I saw them coming forward like a firestorm.

Something was different in their step, something ominous, and there were too many of them walking toward me. I backed into the waiting room and told my mother and my sister, “The doctors are coming.”

And suddenly, there they were, looking at us. White forms leaning against a pastel wall. The air conditioner, the only sound for moments, strained against the late June sun pouring through the expansive glass. Magazines fluttered on the window ledge. One doctor sat down. Another stood beside him, near a nurse. They were watching us -- the waiting people -- the patient’s wife and daughters.

The sitting doctor cleared his throat.

He crossed his leg and looked at us.

He explained what happened, making certain not to leave a space where some errant hope might erroneously crash through and challenge what he had to say. He had to speak quickly, all in one breath. He told us that after the surgery my father had another heart attack. And then: “We are so sorry. He’s gone.”

Gone? Gone where?

That’s the thing about euphemisms. They never speak the truth. They leave all sorts of questions and dangling expectations. “Gone” would imply my father might return, or he’d just momentarily slipped away. Around the corner. Off to the nearest store. Gone might mean there would be footsteps to follow, tracks in the snow, a place to set at the table for later.

Gone would not necessarily mean “never coming back.”

They asked us. They must have. “Did we want to see him?” None of us could.

We went in reverse; we walked to the nurses’ station where a nurse with a sad, trembling smile, handed us my father’s black shaving kit and a small paper sack no larger than a lunch bag. In it, his wedding ring, watch and his paratrooper bracelet. A life reduced to ounces. We moved on, past the painted walls, past doctors and nurses -- a whirl of faces and colors, voices and sounds.

Silently, mechanically, we stepped into an elevator, descended, then walked across the echoing lobby floor. When the exit doors blew open, we walked out into a backdrop of summer, a day so brilliant that my father’s death seemed even more implausible. Our loss, even in its immediacy, was so blinding that, like the day, we could not look at it.

News of my father’s death had already reached the press. We heard a bulletin driving home. A sentence, a string of words so inconceivable, no more comprehensible than if spoken in a foreign language. “Rod Serling died today at 2:20 p.m.” And then, a flash of a hand as someone -- my mother? -- clicked it off.

- - - - - - - - - -

For years I mourned the loss of my father, at first replaying those last days of the hospital -- the waiting, the doctors in their silent shoes, the unimaginable words -- in excruciating, explosive detail as if in the revisiting, the outcome could be changed in some way.

Initially I found that what was left behind defied the reality of his death and perpetuated false hope. His shoes by the door, his comb by the sink still holding strands of his hair, mail just that day addressed to him -- all concrete signs of his presence, possibilities of his return, challenged only by the sudden, insidious silence of the house, the low murmur of voices in the living room, the sea of dark, crushed faces.

I walked aimlessly outside stunned by the normalcy of those obscenely bright summer skies. I knew it was useless, but I would whisper, “Dad, if you can hear me, make the leaf move. Or the bird, make that bird fly now,” and I would wait. I needed something tangible, some acknowledgment that he could hear me. Some sign that I was not losing my mind.

Sitting at his desk, I listened to his Sinatra tapes, looking at notes, letters, photographs. I found cigarettes he’d hidden after he’d “quit.” An interview where he’d said, “All I want on my grave stone is, 'He left friends.'”

I tried to watch a “Twilight Zone.” I listened to his opening narration, but it was terse and somber and his image in black-and-white was not the man I knew.

I panicked when I thought it might be possible I could very soon forget the way he smiled, or the sound of his laugh and the way his voice trailed up the stairs calling me Pops or Miss Grumple or Nanny. I was so afraid that I would lose him, lose him incrementally, lose him for good.

Grieving is not tidy, not organized or easy, but after it slams you, it has nowhere else to go. Understanding this can take years, can take its toll, can excise you off the planet, and it did for me. I finally started seeing a therapist after the insistent prodding of friends. It took more than a year but there I sat with Dr. Feinstein, week after week, in a room with shelves of books and no sunlight. He told me, “You need to visit your father’s grave.” He said it quietly but emphatically. My mother, my friends were all telling me the same thing: “You need closure.” I felt ambushed. Although I had just graduated from college, I was depressed. I had panic attacks and the start of agoraphobia. I was overwhelmed by an acute and all-consuming sadness that sometimes left me gasping for air. A year passed, then another. Seasons vanished. Suddenly summer filled the air in a barrage of color and I finally did what I needed to do. I went to the cemetery.

I walked quickly, looking at gravestone after gravestone. Name after name. None of them my father’s, none of them his.

And then.

His name, his birth date, the date of his death, WWII paratrooper; a small American flag.

In that instant came the finality and inconsolability I’d feared, but I stayed awhile, surrounded by silence, looking again at his name and the flag and then I saw it: a piece of masking tape attached to the stick of the flag and those three words from his interview: “He left friends.”

- - - - - - - - - -

Later that summer, a little more resilient, I began to watch my father’s “Twilight Zones,” doing this more to see him than the actual show. I randomly selected one called “In Praise of Pip.” The episode was filmed at the Pacific Ocean Park, the same amusement park on the Santa Monica Pier that my dad took my sister and me to.

What was so striking, so personal and so moving about this particular story was some of the dialogue. In this episode, Jack Klugman says to his son, “Who’s your best buddy, Pip?”

“You are, Pop.”

Just like the routine my dad and I did.

I watched this episode on a rented projector in a darkened room of our cottage on the lake one hot July afternoon and remained there a long while after the film ended. Through the screen door I could hear the boats on the lake below. An occasional shout rose as a water skier fell and in response, a motor quickly shut down. I heard the gull’s cries in the ensuing silence and then someone shouting, “OK, ready,” and a boat speeding away, transforming the water, reviving the waves slapping thunderously at the shoreline.

I was cognizant of all of the summer sounds in those moments and of this life that moved forward absent my father. I was still haunted by the void, by the reality of this empty space, and yet, those past 30 minutes spent watching his show brought a reconnection with him in a most unexpected way.

In the episode’s closing narration, I watched my dad saying, “The ties of flesh are deep and strong, the capacity to love is a vital, rich and all-consuming function of the human animal, and you can find nobility and sacrifice and love wherever you might seek it out -- down the block, in the heart, or in 'The Twilight Zone.'”

I found it in a darkened room on a summer afternoon. Something invisible, inaudible and, until then, quite mistakenly presumed gone.

Shares