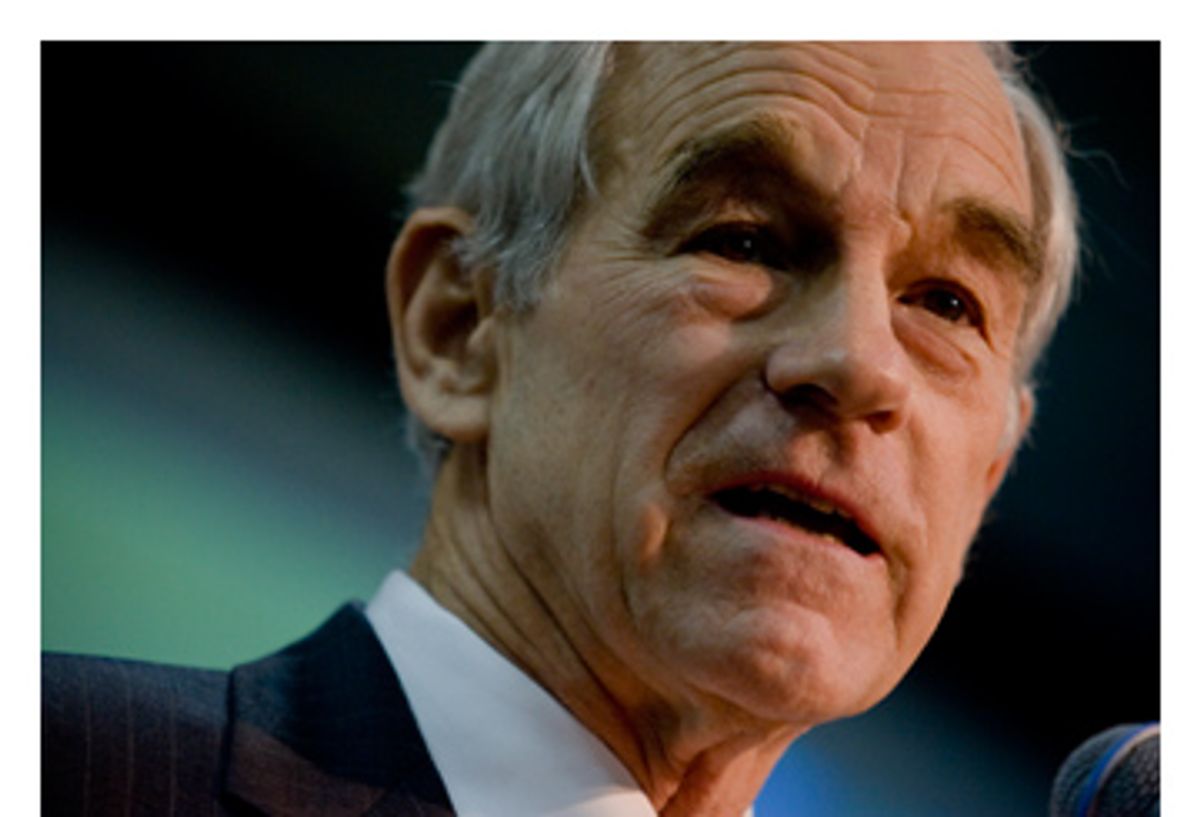

When you’re running near the top of the polls, it’s inevitable that your opponents will gang up on you. But there’s something different about the nature of the attacks Ron Paul is now facing – and, potentially, about their implications.

In the past few days, three of Paul’s rivals – Newt Gingrich, Mitt Romney and Michele Bachmann – have publicly declared that the Texas congressman will not under any circumstances win the GOP nomination. Bachmann called him “dangerous,” while Gingrich said he wasn’t even sure he’d vote for Paul over Barack Obama. Another candidate, Rick Santorum, said there’s no difference between Paul and Obama on foreign policy and that he’d need “a lot of antacid” to stomach voting for Paul. And Jon Huntsman launched a scathing anti-Paul ad in New Hampshire with a simple title: “Unelectable.”

This is not a run-of-the-mill pile-on. Paul’s foes aren’t simply telling Republicans that he’s not the best choice to be their nominee; they’re telling Republicans that he’s unfit to call himself one of them – that he’s an imposter who isn’t due even the most basic courtesy (“Oh sure, if he ends up being the nominee I’ll be with him…”) that major candidates for the nomination are typically afforded.

It’s an attitude that’s also being encouraged by some of the GOP’s most powerful opinion-shaping forces. Rush Limbaugh has been disdainful of Paul throughout the campaign, with his guest host this week – Mark Steyn – keeping up the campaign. Fox News, whose primetime hosts have alternated between ignoring and savaging Paul, has been treating him like a pariah since the last campaign, when Paul was denied a seat at a critical pre-New Hampshire debate. And the New Hampshire Union Leader, which boasts one of the country’s most influential conservative editorial pages, branded Paul “truly dangerous” on Thursday.

The roots of this anti-Paul alarmism go deeper than the racist newsletters that were sent out under Paul’s name in the early 1990s and that have attracted new attention in the past week. Sure, the newsletters (and Paul’s shifting explanations for them over the years) would help make him an unelectable GOP nominee, but rest assured the same intraparty voices would be railing against him with the same adamancy even if they’d never emerged.

The reason has to do with Paul’s noninterventionist foreign policy and his unapologetic mockery of the “clash of civilizations” ethos that has defined the post-Cold War GOP. Today’s Republican Party is dominated by Christian conservatives (44 percent of participants in the 2008 primaries identified themselves as evangelicals) and neoconservatives, who are united in their commitment to an unwavering alliance between the United States and Israel, confrontation with Iran, and a significant American presence in the Middle East. Paul’s warnings about “blowback” directly threaten this consensus.

Thus, with or without the newsletters, Paul has always faced a unique ceiling in the GOP race. There is some appetite (or at least tolerance) for noninterventionism in the party – enough to allow Paul to potentially win Iowa with about 25 percent of the vote and maybe to win some low-turnout caucus states where his grassroots army gives him a leg up. But, as Pat Buchanan told Salon last week, the heart of the party’s leadership and voting base remains very hawkish. So as he’s pushed to the top in Iowa, the GOP’s opinion-shaping class has moved to marginalize him, and his fellow candidates are now happily joining in.

In a way, the outcome of this push is foreordained: Paul won’t be the Republican presidential nominee. At best, he’ll win Iowa, overperform in New Hampshire, gobble up a bunch of delegates in February, and drag the nominating process out well into the spring. But the party is not broad enough for a candidate with his views – and, more to the point, with his enemies – to gain a delegate majority. With every favorable primary-season result he achieves, the “imposter!” cries from the Fox/Limbaugh crowd will only grow louder, and sooner or later it will take its toll. We’ve seen this sort of thing before: Think back to 2000, when the GOP’s opinion-shapers sounded the alarm about John McCain after his 19-point New Hampshire win and convinced the conservative base to regard him as a Democratic stalking-horse.

But for two reasons excommunicating Paul carries some real risks for the conservative establishment. The first is that Paul has an unusually loyal base of supporters, many of whom aren’t even registered Republicans. The second is that Paul, who is 76 years old and has already announced he won’t seek another term in the House, no longer has much to lose. In other words, if Paul decides in a month or two that he was treated unfairly by his opponents and the Fox/Limbaugh crowd, what’s to keep him from bolting the party, claiming the Libertarian nomination, and taking his supporters with him?

Paul, of course, ran as the Libertarian nominee once before, failing to break 1 percent in 1988. But he was far less well-known then. A third-party Paul bid today could conceivably net 5 percent of the vote, maybe even close to 10. It wouldn’t all come from the GOP nominee’s hide, but there’s little doubt his presence in the general election would boost Obama’s prospects.

If there’s one obvious reason for Paul to resist the third-party temptation this time, it’s his son Rand, the freshman Kentucky senator whose future in the GOP could be hurt if his father becomes the party’s equivalent of Ralph Nader. But as they bash away at him in the days and weeks ahead, Republicans may end up giving Paul just the motivation he needs to stick around for the fall campaign.

Shares